On the last day of January, The New York Times announced it would buy the online game Wordle for a price “in the low seven figures.” Talks began earlier in the month, a Times spokesperson said.

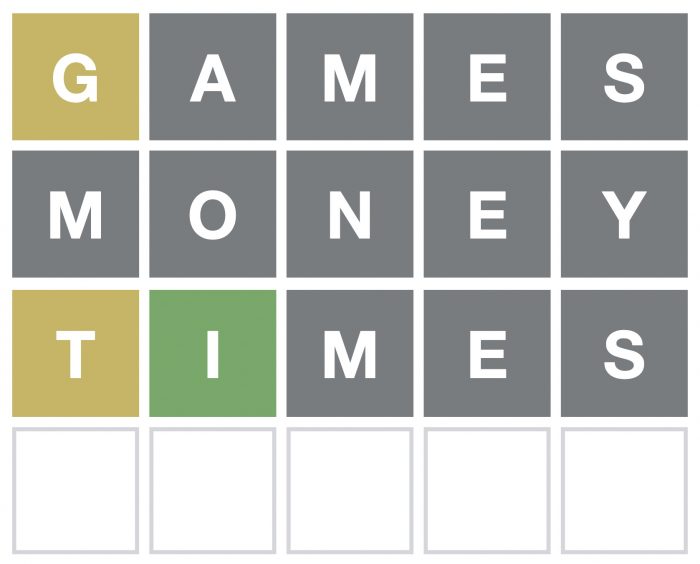

Can I assume you know about Wordle? The one where you have six guesses to get the correct five-letter word using some color-coordinated hints? You may have seen an article about it. Perhaps a tweet or two. The Times purchased the viral game from Brooklyn-based developer Josh Wardle, a software engineer who created the game as a gift for his partner.

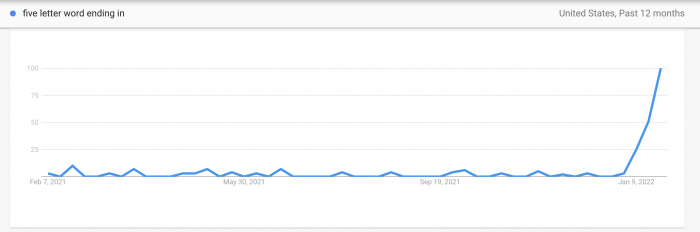

Wordle was released to the public in October 2021. The game had fewer than 100 daily players on November 1 but that number shot up to 300,000 just a few weeks later.

Interest really took off in the new year and at the time of sale, the game has millions of daily players.

The New York Times Games editorial director Everdeen Mason demurred when asked, earlier this month, if the Times was considering purchasing Wordle, but she did say its popularity gave her confidence people were “hungry for more games,” and “more word games” and “unique games” in particular.

“The game has done what so few games have done — it has captured our collective imagination and brought us all a little closer together,” Jonathan Knight, general manager for NYT Games, said in the announcement. (I would give this a “mostly true.”)Immediately after the acquisition became public, there were pay-to-play concerns. Wordle will join the crossword, Spelling Bee, and other puzzles in NYT Games, a standalone subscription that costs $5/month and reached 1 million subscriptions in 2021.

The Times says Wordle — which you can currently play without paying or registering or even seeing an ad — will stay free for the moment.

But how’s this for an ominous clause? “At the time it moves to The New York Times, Wordle will be free to play for new and existing players, and no changes will be made to its gameplay,” the announcement reads. Or, as the way the Times’ own coverage of the acquisition phrased it, “The company said the game would initially remain free to new and existing players.”

🟨⬛⬛⬛⬛

🟨🟨⬛⬛🟩

⬛🟩🟩⬛⬛

🟩🟩🟩💲💲**subscribe to earn more greens

**NYTApe owners earn unlimited yellows— Ben Collins (@oneunderscore__) January 31, 2022

I asked the Times for clarification — free free or free for now? “We don’t have set plans for the game’s future,” Times spokesperson Jordan Cohen said. “At this time, we’re focused on creating added value to our existing audience, while also introducing our existing games to an all new audience that has demonstrated their love for word games.”

Whether or not the game will be put behind a paywall may influence how players respond to copycat versions. (There’s plenty of Wordle-wannabes in the App Store, and you can play a more difficult version of Wordle, and a, uh, #NSFW version online.) If you can play for free — or less — elsewhere, would you?

1500 word essay on whether the NYT buying Wordle changes the moral calculus of Wordle clones in various app stores. This will be 30 percent of your grade and there will not be extensions https://t.co/yfgbxJtvLO

— nilay patel (@reckless) January 31, 2022

Reactions to the sale ran the gamut, but trended toward “I hope this thing I love doesn’t get ruined.”

The reason I find this depressing is because Wordle felt a bit like an earlier version of the internet – one where stuff was free, wasn’t stealing your data/tracking you, wasn’t bombarding you with calls to download apps. And that can’t really exist on the web anymore, I guess! https://t.co/weG9xOqqaW

— Hannah Williams (@hkatewilliams) January 31, 2022

Nyt buying Wordle has “scab vibes” no I will not be explaining this any further

— Katie Notopoulos (@katienotopoulos) January 31, 2022

Creator of Wordle: I can’t keep running this thing; I love the NYT puzzle peeps, they inspired me to make this thing you love, so I sold it to them! Twitter: How dare you give this thing we love a sustaining home!

— Lydia Polgreen (@lpolgreen) January 31, 2022

The NYT is investing in the lettaverse send tweet

— Kevin Roose (@kevinroose) January 31, 2022

assume the price negotiation process for wordle was like

“ok, $1,200,973”

🟩⬛🟨🟨⬛🟨⬛— Ariel Edwards-Levy (@aedwardslevy) January 31, 2022

Others had suggestions for Wordle’s new owner.

Slam-dunk new upsell perk for @nytimes All-Access subscriptions:

A SECOND DAILY WORDLEhttps://t.co/eKXLt2Y84A

— Joshua Benton (@jbenton) January 31, 2022

If I were the NY Times I’d make Wordle free to play but charge 99 cents to post your score on Twitter.

— Hemal Jhaveri (@hemjhaveri) January 31, 2022