This piece originally ran on Big Think.

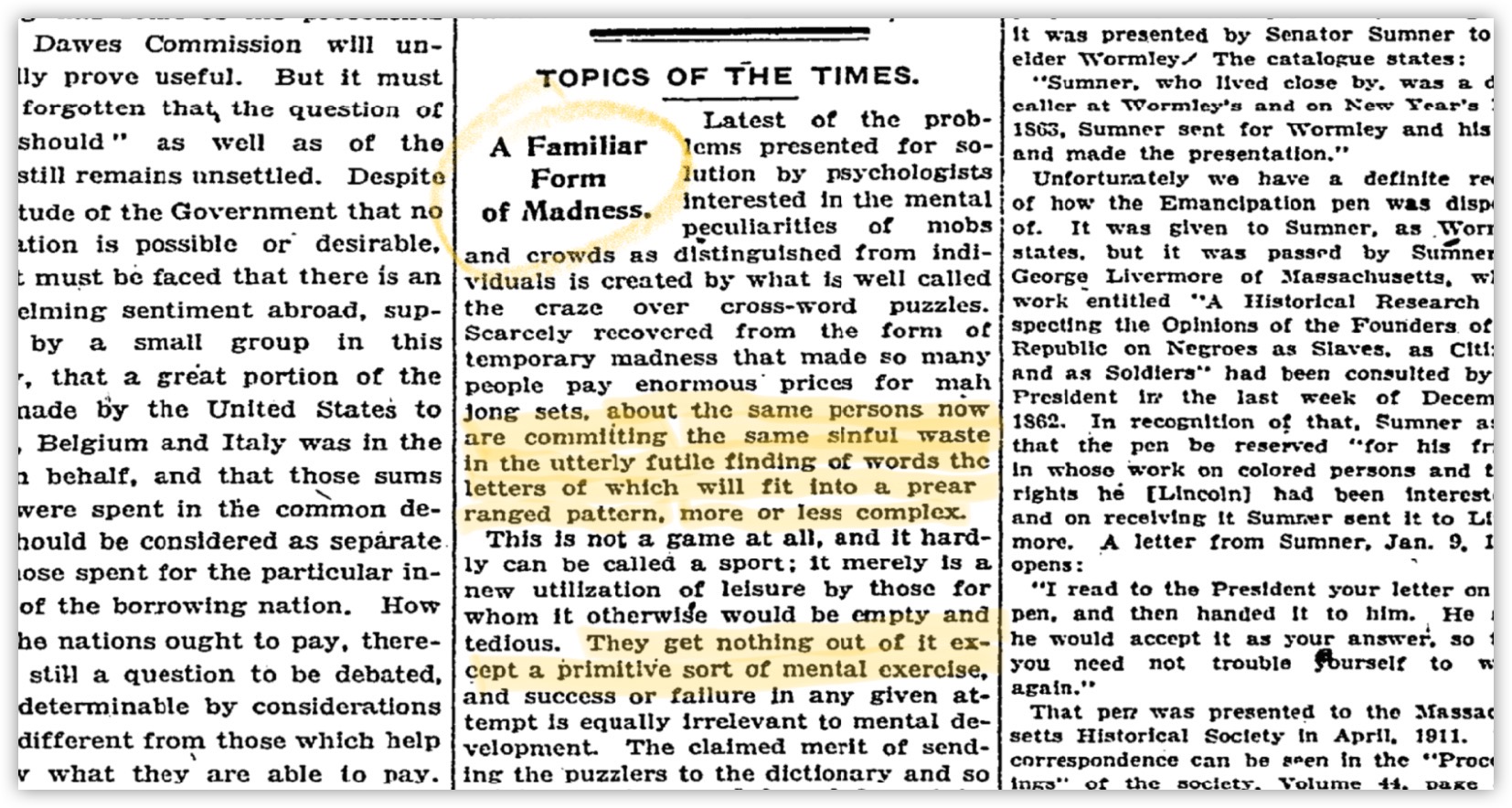

When crossword puzzles first swept across North America in the mid-1920s, The New York Times sneered, calling them “a familiar form of madness” and the next fad after Mahjong. Claims that these puzzles were good mental exercise and a way to expand one’s personal lexicon, via a dictionary, were dismissed.

In another piece published the following year, titled “See harm not education,” the Times argued that learning obscure three-letter words was useless — but it didn’t stop there. “The indictment of the puzzles goes further and deeper,” it said, citing The New Republic, which posited that there wasn’t a worse exercise for writers and speakers due to it fixing “false definitions in the mind.”

This piece prompted a letter to the editor by a reader who retorted, “I am afraid that a good many of your readers will disagree with the views expressed,” pointing out that it was generally agreed that crosswords were educational.

This animosity makes more sense when you understand the origins of crossword puzzles in America: They were popularized via the pages of the original tabloid, The New York World, the “new media” of the day. As far as the journalistic establishment was concerned, crosswords were another mindless fad used as a substitute for good editorial, to keep readers coming back — much like BuzzFeed quizzes were in the 2010s. Tabloids were looked upon as trashy, childish, and plebeian and were labeled the “yellow press” after one of the numerous comic strips contained within them. The New York Times would refuse to publish crosswords for another two decades.

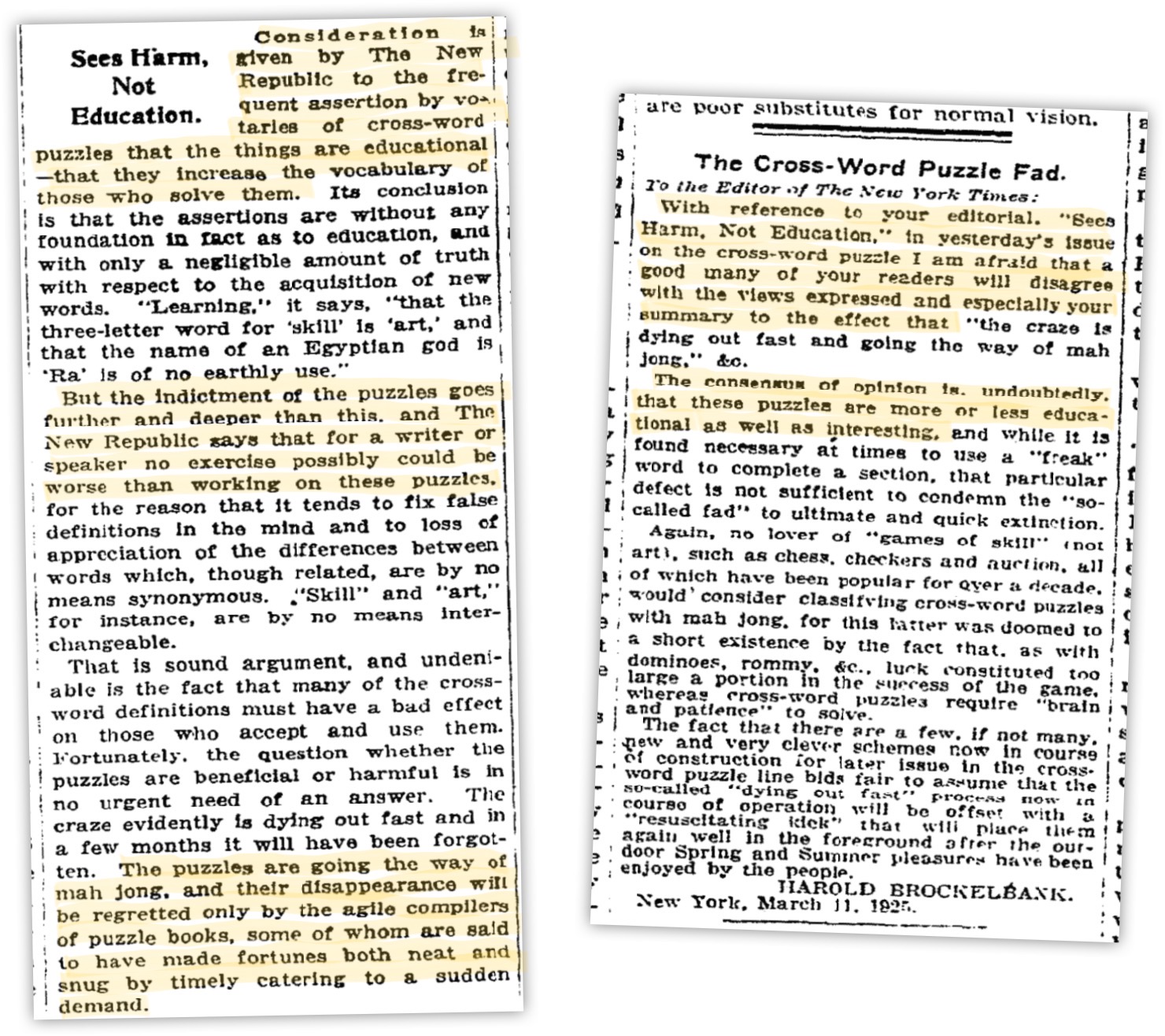

Across the Atlantic in the United Kingdom, the Times of London reported on the U.S. crossword craze with similar disdain, using an ironically tabloidesque headline “An enslaved America.” From 1924:

All America has succumbed to the allurements of the cross-word puzzle. In a few short weeks it has grown from the pastime of a few ingenious idlers into a national institution and almost a national menace: a menace because it is making devastating inroads on the working hours of every rank of society.

The omnipresence of crosswords in the U.S. was described in detail. This “fad” was “in trains and trams on omnibuses, in subways, in private offices and counting rooms, in factories and homes, and even — though as yet rarely — with hymnals for camouflage, in church.” Along with other modern trends, the crossword had supposedly “dealt the final blow to the art of conversations.”

In the London Times’ estimate, over ten million people spent half an hour each day working out the puzzles when they should be working, noting “this loss to productive activity of far more time than is lost by labor strikes.” It even compared them to an invasive weed, stating “The cross-word puzzle threatens to be the wild hyacinth of American industry.”

Judging by reports at the time, this proverbial “wild hyacinth” had invaded the UK by the following year, when reports appeared of Queen Mary, wife of King George V, taking up the pastime. Crosswords were scorned as the “the laziest occupation” and an “unsociable habit.” One British woman took her husband to court for staying in bed until 11 a.m. doing crosswords. Public libraries fought a “war on crosswords” by blotting out the games in their freely available newspapers and limiting access to dictionaries within reading rooms.

An essay titled “In abuse of the cross-word puzzle” noted that early adopters of golf and bridge were abused for their frivolity but now appeared intellectual giants “in this era of puzzles!” — failing to learn a lesson from history, namely, that crosswords would eventually be seen as intellectual too. “Incredible though it may seem,” it also noted, novel reading was scorned by parents not long ago, too. Crossword puzzles (and jigsaws) were different, according to the author: “Was any age ever given over to such stultifying pastimes or labeled with signs of such mental degradation?”

Less than five years after it derided them, the Times of London would give in and print its first crossword puzzle.

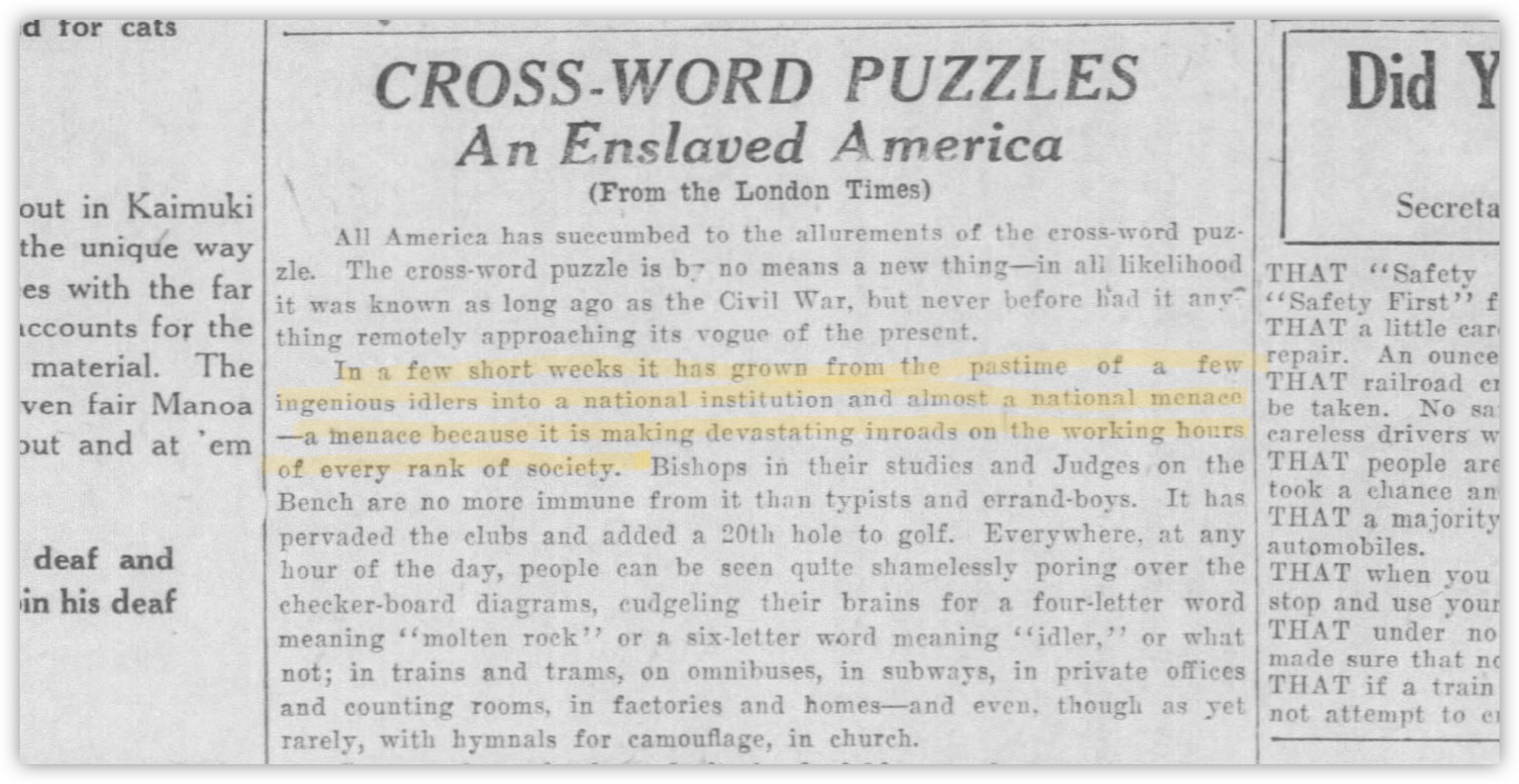

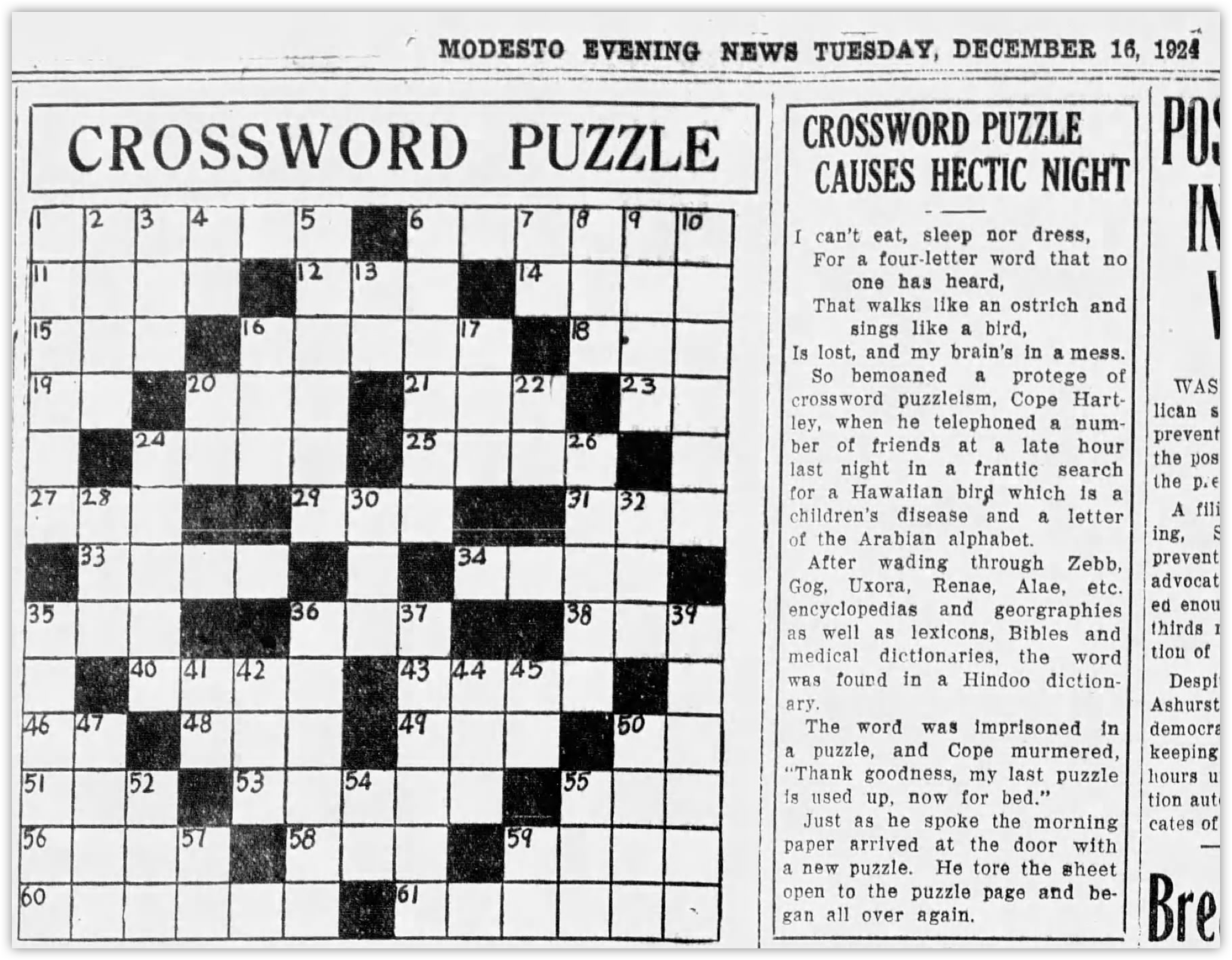

Back in the U.S., the crossword puzzle habit was being pathologized and medicalized, and the term “crossword puzzleitis” was coined — likely in jest — but it would eventually get attention from medical authorities and physicians. One doctor concluded that “crossword puzzleitis” “stole” the memories of his patient. “Crossword insomnia” was another phenomenon reported, akin to late-night smartphone fiddling. Optometrists claimed the habit caused headaches and weakened eyesight.

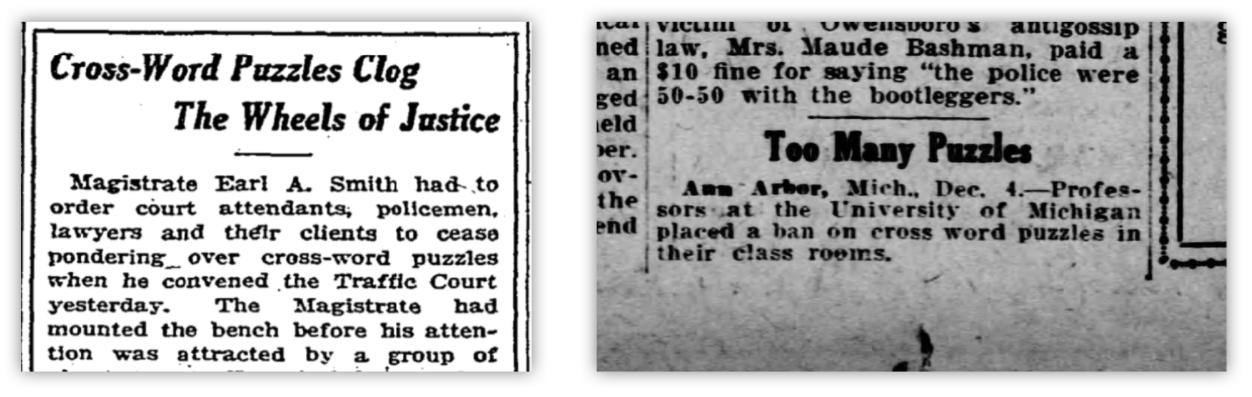

Magistrates lambasted court attendants, police officers, lawyers, and their clients for “clogging up the wheels of justice” by pondering over the puzzles. Academics made similar complaints about their students, and the University of Michigan instituted an outright ban in lecture halls.

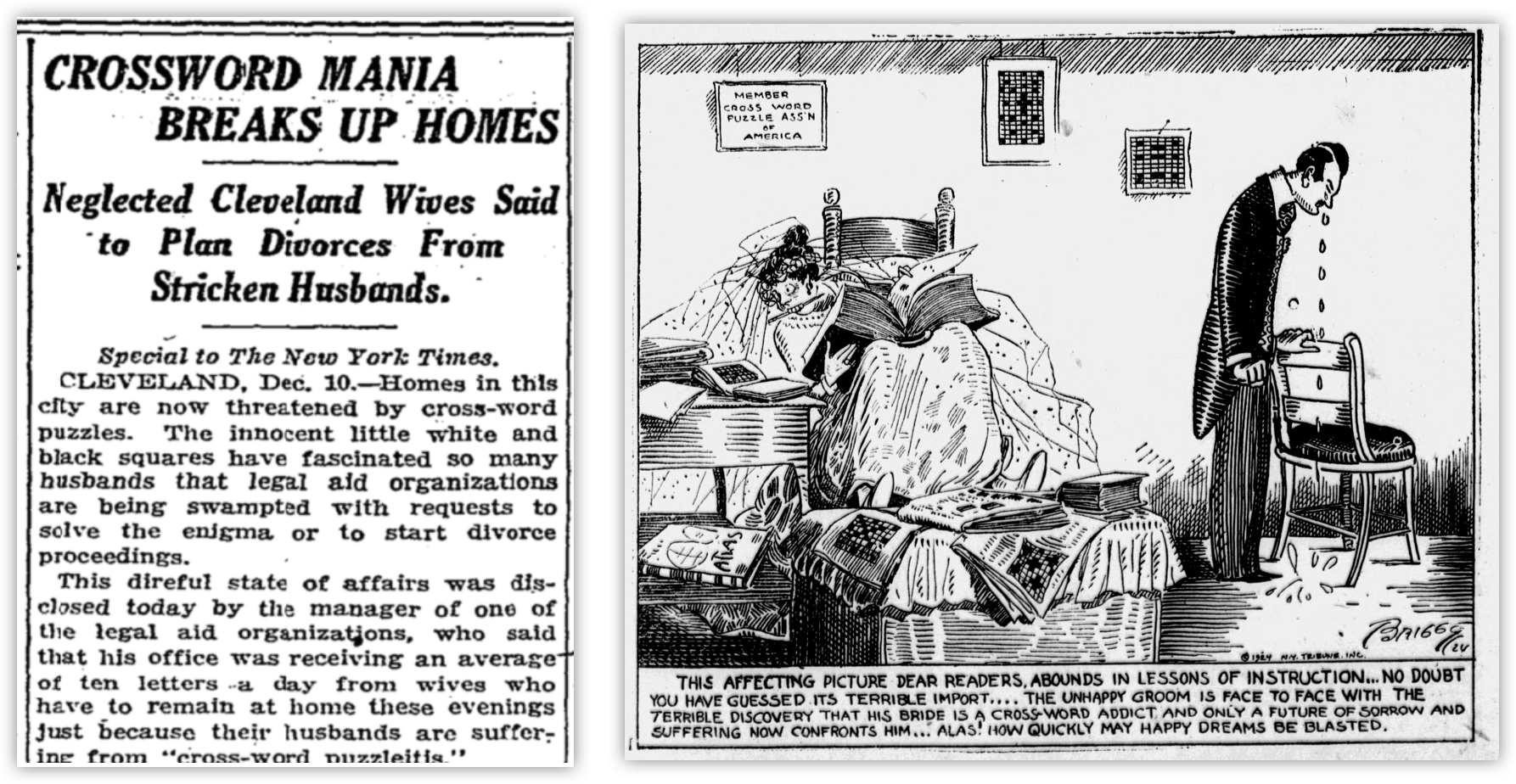

Crosswords were cited as a reason for divorce in more than one case, receiving widespread press attention, including from The New York Times, which ran the headline “Crossword mania breaks up homes.” Other papers published cartoons featuring weeping grooms and puzzle-engrossed brides.

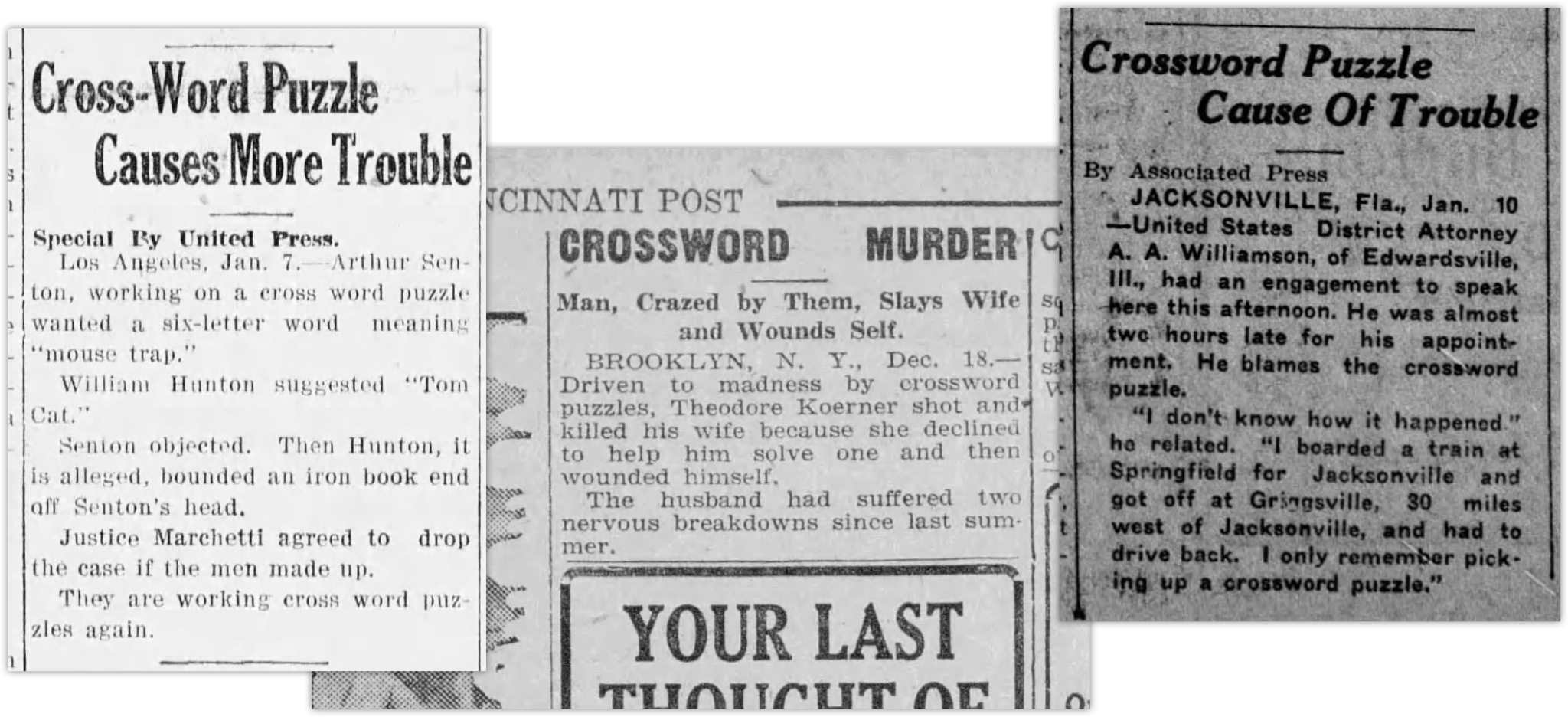

American libraries had the same complaints as British ones in regard to their effect on library habits, and when a U.S. district attorney was two hours late to a speaking engagement, he blamed a crossword puzzle that he had started on the train ride. Physical assault and even murder-suicide were blamed on the crossword puzzle too.

Many of these sensationalist, possibly tongue-in-cheek reports appeared in the very papers printing them, sometimes right next to the crosswords themselves.

By this time, some newspaper editors were defending crossword puzzles, insisting they were beneficial, but it was unconvincing since they were financially benefiting from the craze. Eventually, The New York Times relented, as the U.S. entered World War II — editors decided people needed a distraction and escape. The Gray Lady printed its first on Sunday, February 15, 1942.

“I don’t think I have to sell you on the increased demand for this kind of pastime in an increasingly worried world,” the Times’ first crossword puzzle editor wrote. “You can’t think of your troubles while solving a crossword.”

A century later, word game manias are still happening. Scrabble saw a renaissance on the web and then mobile via Words with Friends in the 2010s. Late in 2021, Wordle gained mainstream coverage in the New York Times. It was praised as being free from the pressures of the hyper-capitalist attention economy; the one-game-per-day limit was held up as enforced digital moderation, ignoring its Pavlovian-esque nature. It was supposedly fun for the sake of fun, not profit and attention.

On January 31, 2022, The New York Times announced it had bought Wordle for a price in the “low seven figures” from its creator, promising to keep it free “initially.” Regarding the acquisition, The Times called games an “essential part of its strategy” to increase subscriptions: Brain teasers to make The New York Times a part of one’s daily routine, like The New York World’s strategy almost a century ago.

Louis Anslow is a writer, technologist, and curator of Pessimists Archive, a project exploring technophobia throughout history.