One exercise I like to use when teaching college students about media is to draw a Cartesian coordinate plane, give them each a list of news organizations, and then have them place each one at some X,Y coordinate. You know the kind of graphing-paper chart I mean — like New York magazine’s Approval Matrix, only with National Review and the AP instead of West Elm Caleb and Neil Young,

I tell them the Y-axis represents a publisher’s journalistic quality — a +10 up at the top is the platonic ideal of amazing reporting, a -10 at the bottom is “The Pope Endorsed Donald Trump.”

The X-axis represents the publisher’s political positioning; from left to right, you might have Jacobin at -9, The New Republic at -6, The New Yorker at -4, the AP at 0, The Dispatch at +4, Fox News at +8, and Newsmax at +10.

You might consider some or all of these placements hopelessly mistaken — which is fine! They make for good classroom discussion. The exercise forces students to think concretely about what they really mean by “quality journalism” and “bias.” It also shows that journalistic quality and political positioning can mix in all sorts of ways. Publishers with no apparent political position can be amazing or terrible; more opinionated sites can choose to stick to facts or to push propaganda and misinformation.

Every time I draw out that blank chart, it reminds me how hard it is to systematically determine the quality of news sites at scale. Sure, any engaged reader who reads a site for a long time will probably come to their own conclusions about its relative merits and demerits. And most well-known sites come with some sort of public reputation; maybe you’ve never read Breitbart, but you’ve probably heard some idea or another about what they produce.

But everyone has had times when they’re confronted with a story from an outlet they’ve never heard of and have to think: How much credence should I give this site’s stuff? And if that’s a problem for individuals, imagine how big a one it is for the algorithms that make decisions like: “Jill shared this story from TastyNewsNuggets.co.uk — should I push it out to the top of all her friends’ News Feeds, or let it die a quiet death? “

There have long been ways to try to do this sort of quality-judging by hand; the most prominent these days is probably NewsGuard, which has rated thousands of news sources as Green (“eh, they’re probably all right”) or Red (“hold on to your brain stem, lots of lies incoming”). Though I’ve been critical of them in the past, it’s a broadly worthwhile effort. But even it can’t capture all the edge cases or provide perfect results.

That’s the backdrop for this new paper in Nature Human Behavior, by Saumya Bhadani, Shun Yamaya, Alessandro Flammini, Filippo Menczer, Giovanni Luca Ciampaglia, and Brendan Nyhan. It’s titled “Political audience diversity and news reliability in algorithmic ranking,” and it’s an attempt to gain some systematic signal from the noise of web traffic:

Newsfeed algorithms frequently amplify misinformation and other low-quality content. How can social media platforms more effectively promote reliable information? Existing approaches are difficult to scale and vulnerable to manipulation.In this paper, we propose using the political diversity of a website’s audience as a quality signal. Using news source reliability ratings from domain experts and web browsing data from a diverse sample of 6,890 U.S. residents, we first show that websites with more extreme and less politically diverse audiences have lower journalistic standards.

We then incorporate audience diversity into a standard collaborative filtering framework and show that our improved algorithm increases the trustworthiness of websites suggested to users — especially those who most frequently consume misinformation — while keeping recommendations relevant. These findings suggest that partisan audience diversity is a valuable signal of higher journalistic standards that should be incorporated into algorithmic ranking decisions.

Or to put it more simply: A news site with a highly partisan audience is less likely to be a good news site. It’s not impossible, to be clear — just less likely.

To oversimplify, social platforms typically use some combination of popularity, network, and similarity signals to determine what makes your feed. Popularity: “So many people are digging this meme — let’s send it to more people!” Network: “A ton of Dave’s friends are loving this link — let’s show it to him!” Similarity: “Lots of people who our system thinks are a lot like Dave love this link — I bet he will too.”

But the past decade or so has shown that an article that is popular with your friends and people like you can still tell you to eat horse paste. So platforms develop their own internal set of signals for quality: Have fact-checkers refuted a lot of this site’s articles? Is it on a domain name that’s been around for a long time, or was it just launched yesterday? Has it pushed disproven conspiracy theories in the past?

Given the speed and scale of social media, assessing directly the quality of every piece of content or the behavior of each user is infeasible. Online platforms are instead seeking to include signals about news quality in their content recommendation algorithms, for example, by extracting information from trusted publishers or by means of linguistic patterns analysis.More generally, a vast literature examines how to assess the credibility of online sources and the reputations of individual online users, which could in principle bypass the problem of checking each individual piece of content. Unfortunately, many of these methods are hard to scale to large groups and/or depend upon context-specific information about the type of content being generated…

Another approach is to try to evaluate the quality of articles directly, but scaling such an approach would likely be costly and cause lags in the evaluation of novel content. Similarly, while crowd-sourced website evaluations have been shown to be generally reliable in distinguishing between high- and low-quality news sources, the robustness of such signals to manipulation is yet to be demonstrated.

The authors here argue that the simple fact of having an ideologically diverse audience should be considered a signal in a site’s favor. They used NewsGuard’s ratings to measure the journalistic quality of 3,765 news sites (at the domain name level). And they used “a comprehensive data set of web traffic history from 6,890 U.S. residents, collected along with surveys of self-reported partisan information from respondents in the YouGov Pulse survey panel.” The surveys allowed each user to be placed on a partisan scale from Strong Democrat to Strong Republican.

First, they looked just at each site’s popularity as a signal of quality. Are the most popular ones also the best ones? Nope — which, to be honest, you probably learned just by dating in high school. There’s a slight positive relationship, but it’s not meaningful statistically; there are tons of high-quality news sites with low traffic and some terrible ones that do quite well for themselves.

Though note that relationship varies depending on your partisanship:

When measuring popularity at the user level, websites that have a predominantly Democratic audience have a significant positive association [meaning more popularity correlates with higher quality], but for websites with a Republican audience, the correlation is negative [e.g., more popularity correlates with lower quality] and not significant at conventional standards.

Next, they took the data on users’ partisan position and their web traffic to measure, for each news site, two numbers: its “mean audience partisanship” and its “variance in audience partisanship.” Let’s say you have a bunch of people who sit somewhere on a 1-10 political scale — 1 being very Democratic, 10 being very Republican. Now imagine two news sites that each get five visitors from this group. Site A’s visitors look like this on the scale:

2, 3, 5, 7, 10

Meanwhile, Site B’s visitors look like this:

5, 5, 6, 5, 6

Both of these sites would have the same mean audience partisanship — 5.4, to be precise. But they would have very different variance in audience partisanship, because Site A is drawing readers from all across the map, while Site B seems to only attract audience from a narrow moderate band.

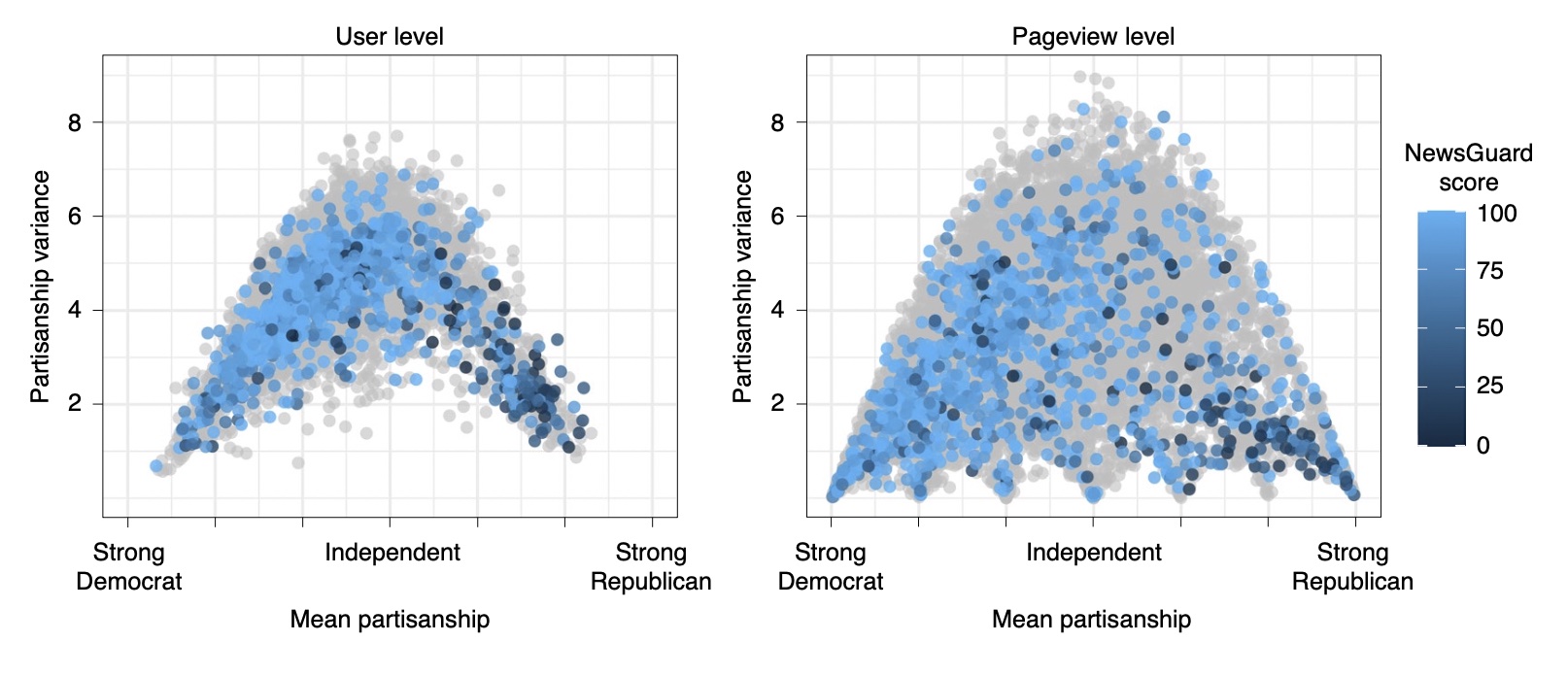

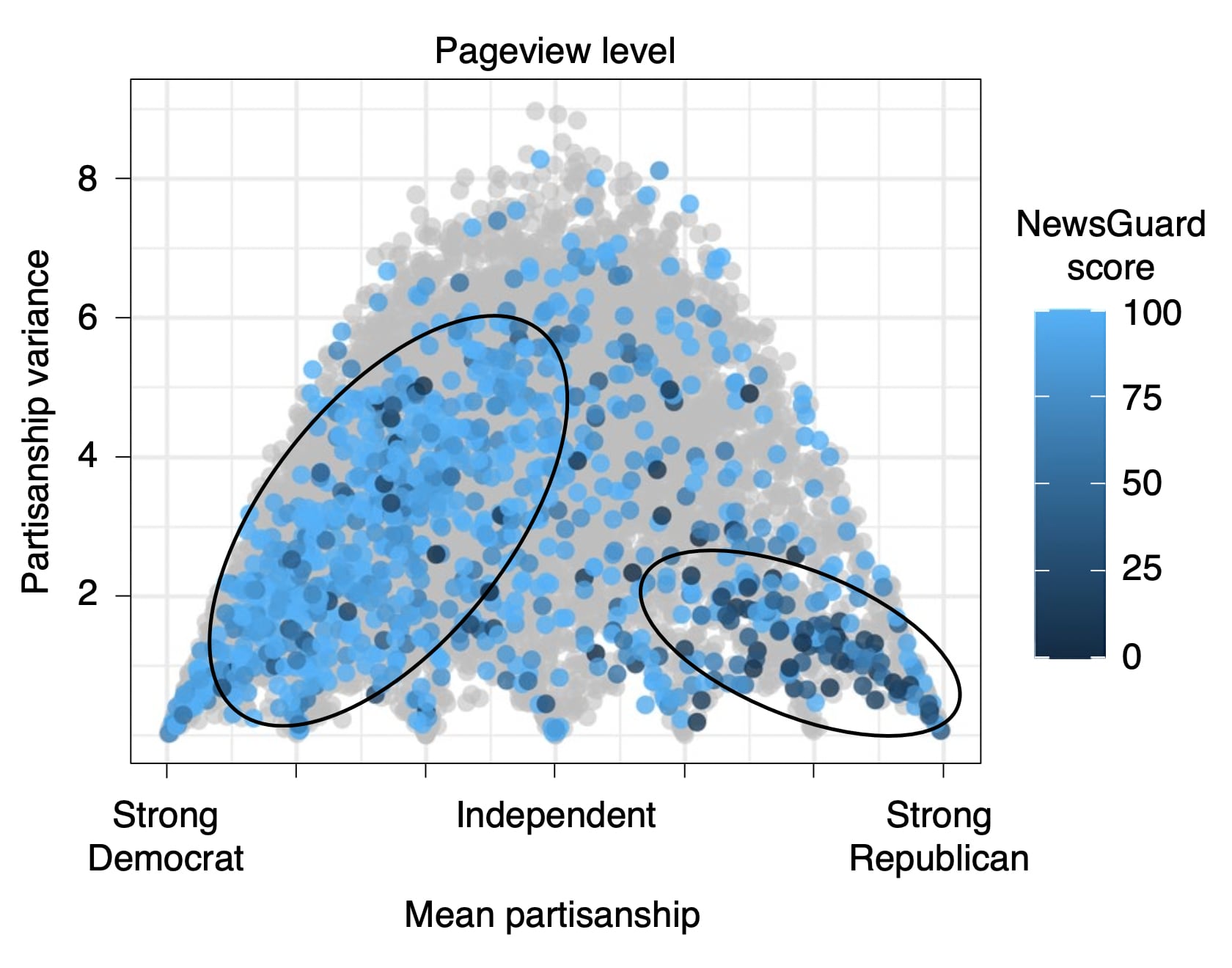

The researchers took those two numbers and plotted all the sites they had data on and this is the result. Get your bearings: The X-axis shows a site’s mean audience partisanship, from left to right. The Y-axis shows audience partisanship variance — sites higher up draw from across the ideological spectrum, sites near the bottom attract only a narrow ideological band. The colors represent each site’s NewsGuard score: the lighter the blue, the higher the quality; the darker the blue, the lower the quality. (The gray sites are ones NewsGuard hasn’t rated.)

You will note that these charts are not symmetrical. Sites with higher audience variance are more likely to be rated high quality if they have a NewsGuard score. (They’re also more likely not to have a NewsGuard score at all, a good indication that they’re not actually news sites.) The closer you move to the bottom, the darker the blues get — meaning the lower the quality gets — they’re not evenly distributed from left to right.

And you can see the two defining sectors of American political media: a bunch of mainstream high-quality sites that are disproportionately (but not exclusively) consumed by those left of center, and a bunch of low-reliability sites that are almost entirely consumed by people on the political right.

Remember: A site’s position on the left or right of this chart doesn’t mean that it produces liberal or conservative content, or has a liberal or conservative bias. It’s not evaluating the sites’ content at all — only its audience. (Liberals on average consume more news than conservatives, which helps push many of these sites’ mean audience partisanship to the left.)

The good news here is that the partisan diversity of a news site’s audience is an effective signal whether its audience is mostly Democrats or mostly Republicans. But it’s very effective on sites with mostly Republican audiences.

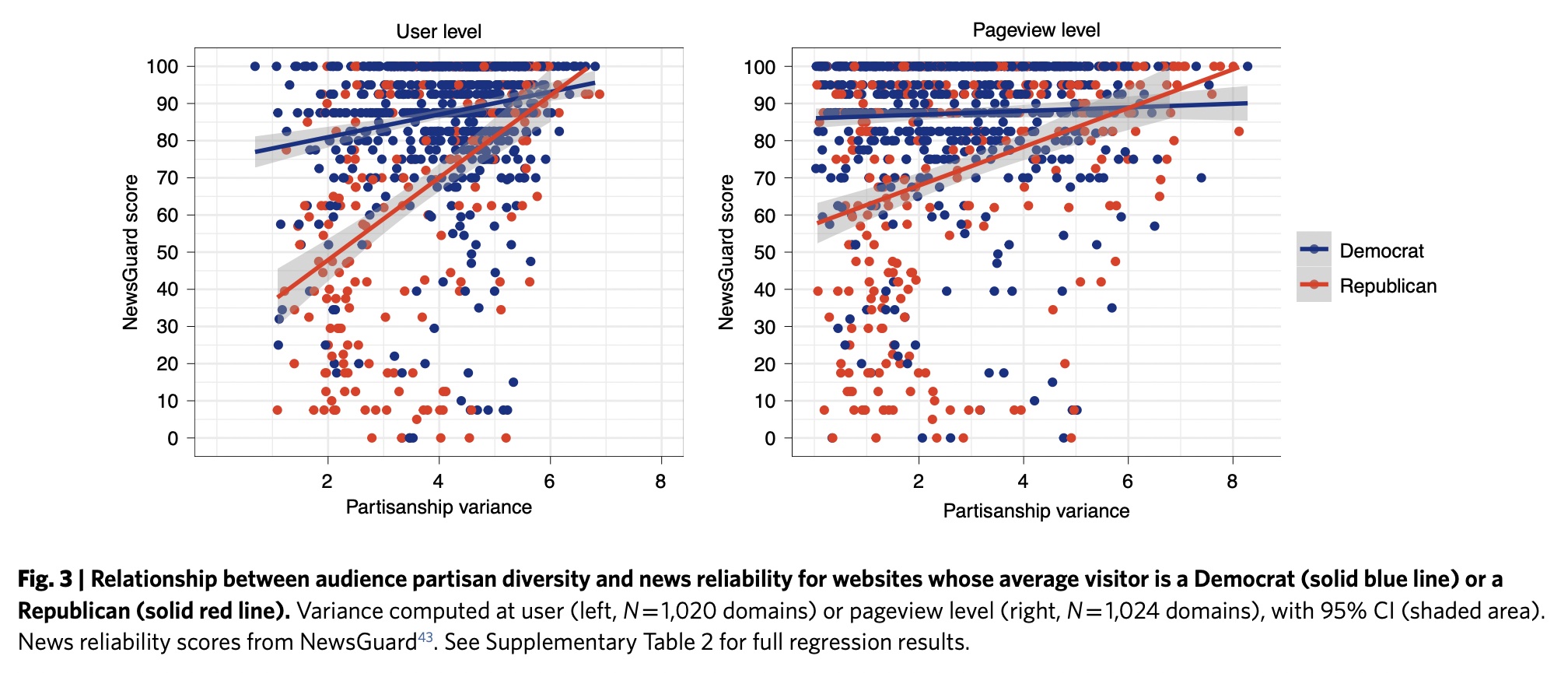

Check this chart: The blue line represents sites whose average user is a Democrat, the red line those whose average user is a Republican. The farther right you go, the more ideologically diverse its audience it.

Especially when you’re looking at it on a pageview level, there’s not a lot of movement in that blue line. The news sites Democrats read have a pretty consistent level of journalistic quality, whether they’re read only by Democrats or, say, 55% Democrats, 45% Republicans.

But the red line is dramatic. Sites that are read almost entirely by Republicans tend to be low in journalistic quality. But sites that are read mostly by Republicans — but also by a significant number of Democrats — tend to be very high in quality. (Call it the Wall Street Journal Effect.)

We also observe that [adding audience diversity as a signal] has strong positive effects for users who identify as Republicans or lean Republican and for those who are the most active news consumers in terms of both total consumption and number of distinct sources…we find that [using the signal] results in improvements for the users whose browsing behavior is most similar to others in their neighborhood and who might thus be most at risk of “echo chamber” effects.Finally, when we group users by the trustworthiness of the domains they visit, we find that the greatest improvements from [including the signal] occur for users who are exposed to the least trustworthy information. By contrast, the standard [collaborative filtering] algorithm often recommends websites that are less trustworthy than those that respondents actually visit.

In essence, the simple fact that a news site attracts a politically diverse audience is a pretty good sign that it’s not garbage.

It’s not foolproof — just as with my classroom X,Y charts always show that there can be high-quality/high-ideology sites and low-quality/low-ideology sites. But when a site attracts readers from both left and right, that suggests readers are finding something valuable about it that isn’t just “it’s on my side, politically.” And these days, that’s the sort of news that’s worth a little extra push.