Journalism is changing, and so is the role of women in the workplace. But the two are not always evolving in harmony. Women substantially outnumber men in journalism training and enter the profession in (slightly) greater numbers, but still only a relative few rise to senior jobs. The pay gap between male and female journalists remains stubbornly wide, and older women — especially if they have taken a career break — find it difficult to retain a place in the industry.

Women in journalism still cluster around particular subject genres. Historically, they were almost totally confined to “pink ghettoes,” but as more women entered the industry, there was an expectation that their opportunities would expand and that they would duly embrace areas that had been traditionally male, like hard news, crime, or politics.

But a byline analysis of U.K. national newspapers in 2012 indicates that some areas still have very few women — in particular politics, sports, and opinion writing. These findings are also supported by qualitative interview data. There are similar lacunae in the U.S. press.

So in addition to the problem of vertical segregation, where women are not reaching the highest ranks of journalism, there is a continuing problem of horizontal segregation: gender division by subject matter.

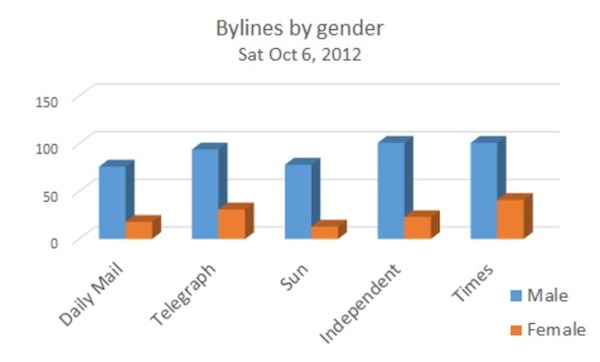

In the autumn of 2012, a gender analysis of bylines in U.K. newspapers, which also coded the different sections of the papers, was conducted at City University London. The survey looked at five national papers over seven days, during two separate weeks a month apart.

The total ratio of male to female bylines was not dissimilar from previous Women In Journalism surveys in 2011/12, which recorded a 78/22 split in favor of men. But what was of interest was the breakdown of topics, which showed a huge variation.

In some cases — especially but not exclusively the softer lifestyle areas — there were reasonable representations of women. But in other places, the number of bylines was scarce to non-existent. This wide difference in gender bylines by subject demonstrates what is apparent from interviewing and anecdotal evidence: Women in news organizations frequently talk about how they are encouraged to do the softer feature lifestyle stories and discouraged from the harder end of news.

The number of female political reporters in Westminster has increased since the 1980s, but there are still relatively few of them. When Press Gazette published the 50 leading political reporters in 2012, it included only three women, ranked at numbers 16 (chief political reporter of the Financial Times), 36, and 39. And according to the byline survey, on some papers — the Daily Mail and The Independent — the imbalance in political reporting in late 2012 is overwhelming, with the vast majority of political stories reported by men.

Overall, the percentage of women journalists in the parliamentary lobby is 23 percent — almost exactly the same as the proportion of female MPs in Westminster. But there is only one female political journalist listed among magazines and periodicals and none of the daily papers, broadcasters, or main political websites has a female political editor. The same holds true here: Even though there are some women, they are not finding their way to the higher strata in significant numbers. [See update below.]

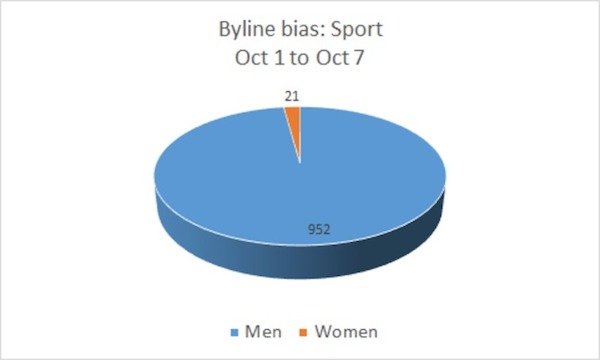

After politics, a second area where female bylines are pretty much invisible in the content analysis is sports journalism. Maybe this is unsurprising, because sports, even more than politics, is perceived as an overwhelmingly male activity. In 2011, a wide ranging German survey on press coverage of sport across 80 newspapers in 22 countries revealed that 8 percent of the articles were by women.

In the U.K., it appears that this figure is even lower — fewer than 5 percent of sports journalism in the national press is written by women. In 2012, only two of the Press Gazette Top 50 sports reporters were women. That said, in March 2013, Alison Kervin was appointed by the Mail on Sunday as the first female sports editor of a U.K. national newspaper.

A third significant area with a noticeable gender imbalance is opinion writing. Just as the obituary columns give an impression of a world far more than 50 percent male, the same is true in the comment columns. This pattern is demonstrated in the same two-week content analysis from autumn 2012, which also analysed the gender of comment piece bylines. This is confirmed in the Guardian datablog, which analysed three national papers and associated websites and found that women had written a mere 26 percent of the opinion pieces.

In the U.S., such is the dearth of female opinion writing that a pressure group and website, The Op-Ed Project, was set up to highlight the issue. The Op-Ed Project figures claim that only 20 percent of comment pieces in the U.S. media are by women and they campaign for the publication of a greater range of voices so that the proportion of comment writers who are female can grow.

The Columbia Journalism Review published a lengthy analysis of this deficit entitled: “It’s 2012 already: why is opinion writing still mostly male?” It compared “legacy” and new media, and found that women had a better chance of publication in digital form (33 percent compared to 20 percent in print) — but there was a sting. The online commentaries written by women on sites such as The Huffington Post were twice as likely to focus on “pink topics” — described as the “four Fs” (family, food, furniture, and fashion), plus of course the discussion of women and gender. In contrast, only 14 percent of women’s opinion pieces in “legacy” media were on these topics. It attributed this to the “silo tendency” of new media, where writers are more likely to be writing for like-minded individuals.

Over the past decade, areas such as conflict reporting and economic journalism have seen far more women take prominent roles. But this evidence shows that there still remain a number of subjects — softer lifestyle features on the one hand, and politics, business and sport on the other — that have overwhelmingly disproportionate numbers of one gender. Journalism might be better served if there was a more conscious effort by editors and managers to counter such horizontal segregation in the workplace.

Update: This post has been updated due to an error in the original article at The Conversation. That article made a claim that there were no female political correspondents at the Daily Mail. This is not the case.

Suzanne Franks is a professor of journalism at City University London. She was formerly director of research at the Centre for Journalism, University of Kent and a news and current affairs producer for the BBC, working on Newsnight, the Money Programme, and Panorama.

This article is based on research carried out for Women and Journalism, a challenge published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and IB Tauris.

This article is based on research carried out for Women and Journalism, a challenge published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and IB Tauris. ![]()

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article.