Why “Sorry, I don’t know” is sometimes the best answer: The Washington Post’s technology chief on its first AI chatbot

Earlier this month, The Washington Post debuted its first generative AI chatbot, Climate Answers. The chatbot’s promise is to take in readers’ most pressing questions about climate change science, policy, and politics, and turn out a brief summary of the Post’s reporting on that topic, with full citations and link outs to relevant stories. The chatbot pulls on years of reporting from the climate desk and was built in collaboration with the newsroom’s beat reporters.

I sat down with the Post’s chief technology officer, Vineet Khosla, last week to discuss the novel product and how it fits into the Post’s larger AI strategy. Khosla joined the Post last year after nearly two decades working in Silicon Valley. He was among the first engineering hires on the team at Apple that developed Siri and for years managed maps routing at Uber.

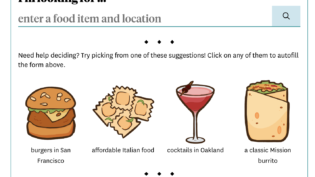

Khosla says while there’s potential for a chatbot that delivers breaking news, Climate Answers is not that chatbot. Rather than surfacing the Post’s latest reporting on an extreme weather event or environmental disaster, Climate Answers was built to synthesize years of reporting by the Post on more evergreen topics. Suggested prompts on the homepage include “What happens if the Atlantic Ocean circulation collapses?” or “What do I tell people who don’t believe in climate change?”

Still, Climate Answers is programmed to update at least once a day, allowing it to keep up to date with the news of the week, if not the hour.

This is just the Post’s first pass at a generative AI chatbot. Khosla says more topic-focused products are coming down the line. In our conversation he floated the idea of a technology, business, politics, or crime-focused sibling to Climate Answers, or a newsier chatbot that delivers sports scores or weather forecast updates. But he says the Post started with climate for good reason.

For one, Khosla claims the beat is fact first. Climate reporting is filled with figures, jargon, and scientific explanations that are often embedded within narratives and longer form articles. The pitch is that Climate Answers can sift through those stories — possibly tens of thousands of words of reporting — synthesize that information and surface the bare facts.

“It’s a domain that leads very naturally to a lot of question [and] answer-style interactions where people are curious,” Khosla said. “Those facts are always hidden somewhere, in a story you would not even imagine.”

We’ve seen other news publishers experiment with AI-powered chatbots to answer questions about financial markets and restaurants — and avoid beats like politics and elections which are often marked by more strategic analysis and polarized points of view. The Post appears to be taking a similar approach.That’s not to say climate change coverage isn’t filled with deniers, political actors, and outright propagandists. Topics like nuclear energy and carbon capture, for one, are still politically contentious and controversial even in the scientific community. The facts can be used to support or criticize these climate solutions.

“This is a very hard problem to solve, right? One person or a group’s perspective will be very different from other people,” said Khosla, claiming his team had discussed this particularly sticky issue at length. “The stance we take at a product level is, if we have written about it, if we have put out a news report about it, if we have published an opinion on it, we stand behind our journalists. We don’t want a second layer of editorial. That job has been done by our newsroom. It’s not the AI’s job to reject that.”

There is also the concern of amplifying disinformation. If the Post has reported on climate disinformation — even if solely to debunk it — how can Khosla’s team guarantee Climate Answers won’t take those quotes at face value? Donald Trump, for one, has frequently claimed offshore wind turbines are killing whales during his stump speeches (The Post called out that lie in 2022).

Well, Khosla says he can’t guarantee anything. “There’s just no denying it can happen,” he said, adding that the guardrails they’ve built specifically try to avoid scenarios like this. “If our news report said, ‘as per XYZ and that is completely false because the scientific community doesn’t disagree’ then I’m pretty confident we won’t quote the first person.”

Testing at the Post included internal red teaming, where a section of the product team who was not involved in building Climate Answers audited it and tried to work around these guardrails. The climate desk has also been with the project since inception, according to Khosla.

“We are working with them literally daily,” he said. “They are the experts, that is their original reporting. If there is a problem with the model, you and I will not be able to catch it as well as they will be.” This constant tweaking has led to changes in the style and brevity of answers, alongside addressing factual inaccuracies. The chatbot was even circulated among all Post employees to participate and give feedback.

“We have set it up in a big tech style, with a development environment and product release environment,” Khosla said. “When we do a significant leap in the model, we do adversarial testing.”

Climate Answers was built on top of GPT, OpenAI’s foundation model. But Khosla gives little credit to OpenAI for the product’s success, calling the underlying large language model (LLM) relatively interchangeable. “It is the fine-tuning that we do on top of it and it is the retrieval augmented generation that we do on top of it, which are really making the product,” he said. “What we have built over here is an AI platform that is foundation model agnostic.”

Currently, Khosla’s team is experimenting with powering Climate Answers using alternative LLMs, including the Meta-developed Llama, and Mistral, released by the French AI company of the same name. “What’s powering [Climate Answers] right now will most definitely not be the same thing that powers it two to three months from now,” he said. “You already might be in an experience where you’re getting an A/B test and you don’t know it.”

To me, Climate Answers stands out first and foremost for its novel model for citations. Products like ChatGPT have been failing to produce even basic URLs to articles it cites, including, as I recently reported, to its partner publications. Perplexity, a generative AI search engine, has been lambasted in recent weeks with plagiarism allegations and Forbes has threatened a lawsuit for copyright infringement.

Climate Answers meanwhile doesn’t simply link out to the Post article it’s citing with a hyperlink in parentheses, as those two products do. The chatbot includes full headlines and deks and header preview images of stories it cites. When you click on a story it even previews the text in which the information appears, pulling out a few paragraphs around the information to place the citation in its context.

“What we are building over here is very different. These are engaged and curious people who trust news and journalism and who know fact-based reporting is a better way to get answers than Vineet’s personal blogspot.com,” said Khosla. “We want to show you the exact paragraph, because we actually believe this curiosity is gonna lead you to click on it and go and read further.”

Even though the goal is to answer a given question and redirect the user to the Post’s original reporting, Khosla isn’t afraid to turn users away. For one, if the scan of the Post’s climate coverage fails to find a story on the topic you’ve asked about it, Climate Answers will not attempt to respond, instead displaying this message: “Sorry, but we could not generate an answer to your question. This product is still in an experimental phase.”

“For Google, that might be failure mode. So you should always give an answer,” said Khosla, explaining the Post’s business model looks very different. “But for us, that is success. ‘Sorry, I don’t know’ is a good answer when you’re not sure.”

The chatbot has already received some backlash, in part because of these restrictions. Shortly after its launch, some users noticed that Climate Answers was declining to answer questions about generative AI’s energy consumption and impact on climate change. Instead of noting that AI data centers are already using as much energy as a small country, the chatbot simply outputs that same declined answer message.

The irony was not lost on many: The Post was contributing to this energy consumption issue, in its own small way, with the launch of Climate Answers.

WaPo: Detailed reporting about how “AI” is contributing to the climate crisis, including delaying the decommissioning of coal-fueled power plants.

Also WaPo: Let’s set up a chatbot to provide possibly false summaries of our articles on the climate crisis!https://t.co/MXfZqxB6gU

— @emilymbender@dair-community.social on Mastodon (@emilymbender) July 11, 2024

“To be clear, we have not trained it to not answer that question. I want to be very clear about that,” said Khosla. In my own testing, I encountered the same problem with questions like “what is generative AI’s impact on energy consumption?” A spokesperson for the Post, however, shared screenshots of several alternate phrasings to the same question that would surface full answers, including “what is the Artificial Intelligence impact on the power grid?”

On first pass Climate Answers appears to mainly be a unique tool for recirculation. It pulls out stories not just from the past month of climate coverage, but going back years into the Post’s archives. While the Post’s audience team is closely monitoring Climate Answers’ analytics for click-through traffic to stories, a traffic bump may not be the best measure of success according to Khosla.

“Traffic is a signal, but there’s multiple ways the product succeeds, right? Like if it can engage people for a longer time span. It could help them justify the cost of the subscription,” he said. “It should lead to growth, it should lead to more engagement, it should lead to more habit building, but really, it’s about our customer and giving them more value for their money, giving them more reasons to get the right answer from us.”