It’s a warm afternoon in mid-April and journalist Jorge Caraballo Cordovez makes his way down a busy street in East Boston. Passing convenience stores, a Colombian bakery, and a hair salon, Caraballo stops to talk with nearly every passerby in this primarily Latino neighborhood in Boston, Mass.

He hands everyone a postcard, and speaking in Spanish, asks them about their living situation: Has their landlord tried to raise their rent recently? Have they gotten an eviction notice?

Caraballo meets a man working two jobs who moved to a further-out suburb because he could no longer afford his rent. He speaks with a young mother, living in a four bedroom apartment with three other adults and four kids, whose landlord wants them all to leave.

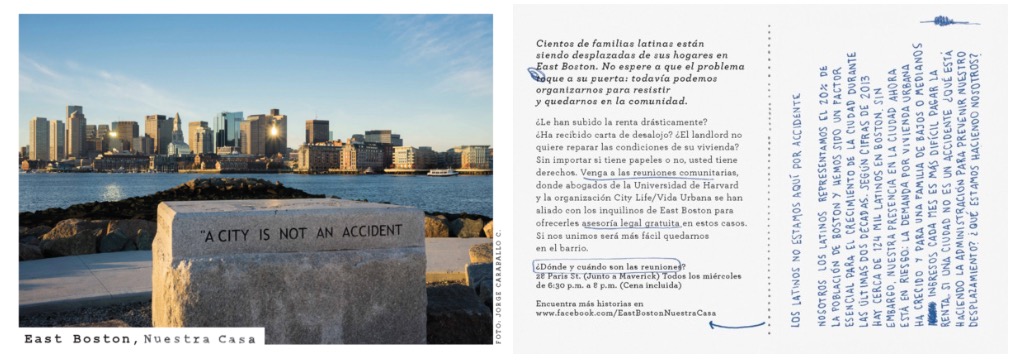

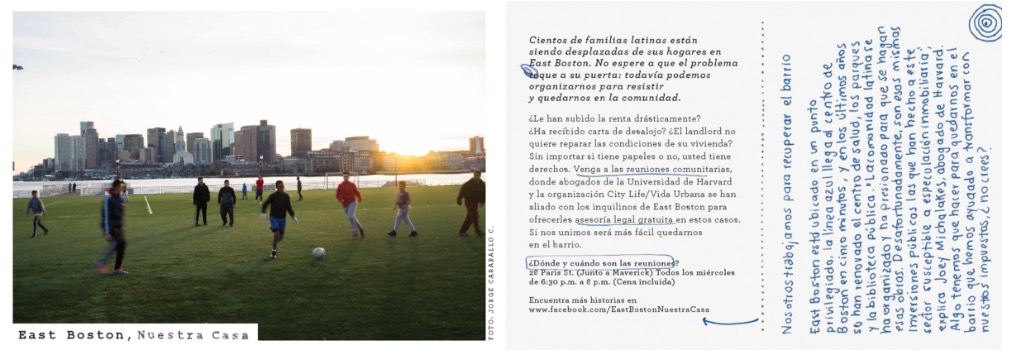

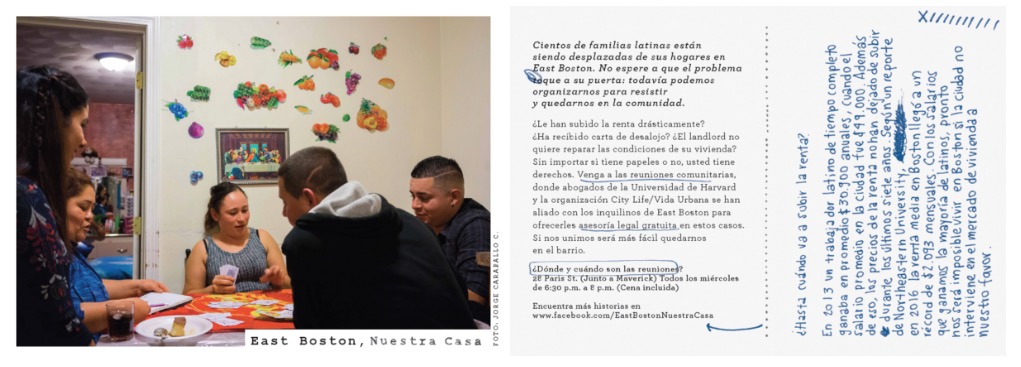

The postcards Caraballo hands out are the heart of a reporting project he launched last year called East Boston, Nuestra Casa (“East Boston, Our Home”). The front of each postcard features one of 12 photos Caraballo took of life in the neighborhood. The back shares the story behind the photograph, offers readers background about displacement in East Boston, and shares information about tenants’ rights and legal resources.

Caraballo began the project as part of his graduate studies at Northeastern University, where he graduated with a master’s degree in media innovation this spring.

While the topic of gentrification has been covered in both the local English and Spanish-language press, Caraballo wanted to find a way to report on the topic in a laser-focused manner while also finding a way to share actionable information with the community.

He decided to do that through the postcards because he wanted to provide information in a memorable, concise way that would be accessible to everyone in the neighborhood.

“How can journalism help to inform these people about the resources to stay in the neighborhood, or at least the rights they have, so they don’t leave their apartments as soon as their landlords say, hey, you have to go?” Caraballo asked. “There are resources. You have rights. It doesn’t matter if you’re documented or undocumented. That’s the question. How to do it is the postcard. It’s a way to solve the language problem and the lack of information.”

On his walk around East Boston on that April afternoon, the people he spoke with were generally grateful for the information on the postcards. But for at least some, it was too late. He spoke with a couple who left the neighborhood after their rent skyrocketed, but who were trying to find another place nearby so their two kids could stay in their current school. They didn’t know they could’ve resisted their landlord’s attempts to force them out.

“If I had known this, we would have fought until the end,” the man told Caraballo in Spanish. “But we didn’t know.”

As Caraballo continues around the neighborhood he stops passersby to hand out postcards, pops into a small fruit stand to leave a stack of postcards on the register, and drops by a laundromat to distribute the cards as well.

Nicknamed Eastie, East Boston, has long been home to subsequent waves of immigrants arriving in Boston. The neighborhood is now 57 percent Hispanic, according to U.S. Census data. The neighborhood is filled with new construction and advertisements for new buildings. The median home value in East Boston is $427,700, according to Zillow. That’s a 14.8 percent increase over last year, and the real-estate site predicts that home values will climb another 5.5 percent over the next year.

For Caraballo, the project is a mixture of activism and journalism, and he said it’s a combination that doesn’t contradict itself.

“Absolutely, it’s advocacy and it’s journalism. They complement each other,” he said. “It’s journalism because I’ve been very transparent. I’ve been interviewing as many people as possible to get as many perspectives as possible. The goal is to inform people. That’s journalism. But it’s also advocacy. In order for that information to be useful, you need to get organized.”

With funding from Northeastern, Caraballo was able to print 5,000 postcards. (The design, which was created by designer Laura Pérez, has been opensourced.) Caraballo distributed the cards to people directly on the street and deposited them in mailboxes.

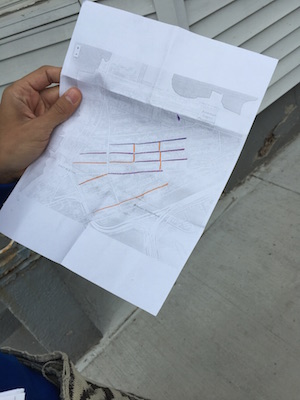

Following a color-coded map that detailed which streets he’d already covered, Caraballo canvassed some of the streets he hadn’t yet visited. Looking at the names on buildings’ mailboxes, he left postcards at the addresses with Hispanic-sounding names.

Following a color-coded map that detailed which streets he’d already covered, Caraballo canvassed some of the streets he hadn’t yet visited. Looking at the names on buildings’ mailboxes, he left postcards at the addresses with Hispanic-sounding names.

Caraballo also created a closed Facebook group as a hub for conversation and his reporting. With more than 200 members, he shares information from interviews he’s conducted with government officials and others in the neighborhood, news stories, and reminders about the meetings.

And Caraballo also worked with others to find ways to make the postcards even more interactive. Youth from Zumix, the community arts organization, participated this semester in a class focused on radio production, which focused on telling stories about displacement and the changing neighborhood.

The students helped distribute the postcards. Caraballo also spoke with the class of 12- to 18-year-olds about the project, and he was included in one of the stories that the students produced that aired on the radio station.

“The whole process made a big impact on them,” Brittany Thomas, Zumix’s radio station manager, told me. “Jorge made it into the story as an example of a local effort to work toward a solution.”

Zumix and Caraballo also worked with students at MIT’s Civic Media Collaborative Design Studio. The co-design studio is led and taught by MIT professor Sasha Costanza-Chock, and one of the groups in the class produced a podcast featuring stories of displacement in East Boston and the East Boston, Nuestra Casa project.

The group experimented with augmented reality to connect audio to the postcard, using Layar, an app that let people scan the postcards and hear stories from those affected by displacement. They also tried VoJo, a platform developed at the MIT Media Lab that lets people share stories via phone calls and text messages.

“Instead of always thinking that we need to make an app to ‘solve’ some problem, there are often really strong existing community processes,” Costanza-Chock said. “Wherever community is targeted by oppression, there are often strategies of resistance. The question is how a design can amplify some of those powerful existing projects, or frameworks, or approaches that are coming out of community organizing models.”

Because the project was centered around academic year efforts, the projects have mostly all come to a close. Caraballo returned to his native Colombia at the end of May as his student visa was expiring.

He said he sees East Boston, Nuestra Casa as just one tactic in the ongoing organizing effort against gentrification in East Boston.

“A lot of times, success is measured by how you make it bigger, make it sustainable, or extend it to other projects,” he said. “But I think that this tactic is done. I distributed these 5,000. I believe that I’m helping to spread this information to spark a conversation and to put it in as many hands as possible.”