Humanitarian crisis journalism can be tough to read if you don’t have to do it for your job. And the organizations that publish it have struggled to make it work financially, even if they’re nonprofits.

Humanosphere, which covered the global fight against poverty and inequality, went “on hiatus” in 2017. News Deeply cut half its sites last fall.

“Reporting on humanitarian affairs and international public interest journalism seems to be at the sharp end of the crisis in journalism,” said Martin Scott, a professor at the University of East Anglia who studies humanitarian journalism (and wrote about the subject recently for our sister publication Nieman Reports). “It’s expensive to produce. It’s unlikely to generate revenue because the audience for it is often very small. So very few news organizations do it.”

The New Humanitarian hopes to buck that trend. TNH is the relaunch of IRIN (originally the “Integrated Regional Information Networks”), which after 19 years as part of the United Nations left in 2015 to relaunch as an independent nonprofit.1 Headquartered in Geneva, it’s hired a former New York Times executive to oversee its editorial coverage and make it appealing to a wider group of readers. And TNH’s director, Heba Aly, believes that, as the nature of international crises changes, audiences will be more compelled to consume journalism about them if only because they are more likely to be affected.

“More and more humanitarian crises are having global repercussions,” Aly told me, mentioning climate change and the exodus of refugees from Syria as just a couple of examples. “The traditional way in which the world used to respond to crisis — that narrow group of people who would deliver aid in kind of a ‘foreigner helps poor victim’ way — is no longer enough…We hope and believe that there’s a much wider group of people who now feel they have a stake in these issues.” Humanitarian crises sometimes hit the international news and then fade out of the spotlight; one of TNH’s goals is to continue to hold the focus on these “forgotten crises.”

Aly believes that The New Humanitarian can also play a major role in holding the foreign aid sector accountable. “We do a lot of reporting that unearths UN corruption scandals, or sexual abuse within the aid sector, or policies that do not seem actually intended at helping people in need,” she said. “This is a sector that controls billions of dollars. That’s where I think we fill the biggest gap, in being able to shine a light and hold the powerful players in this space accountable.”

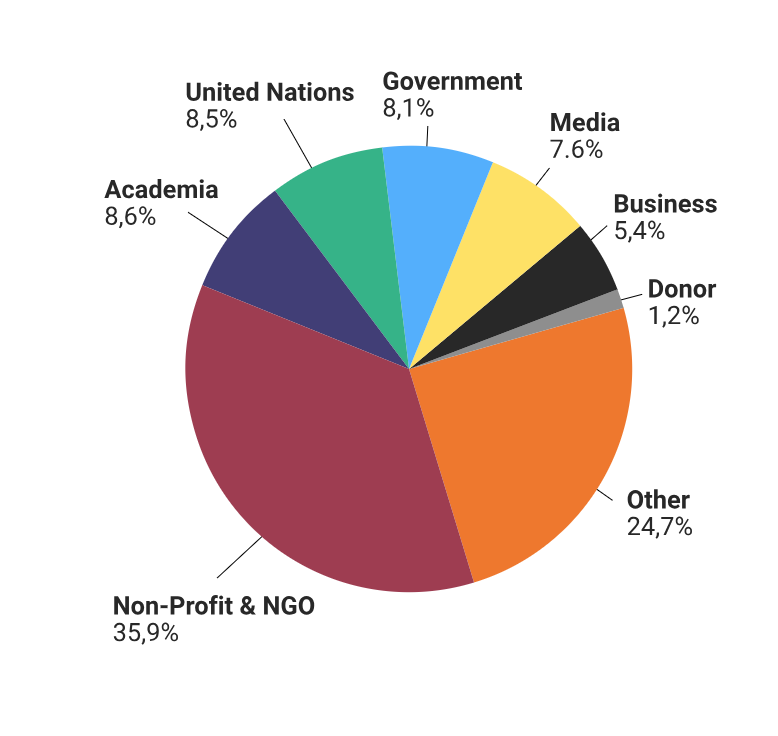

In Aly’s 2019 prediction for Nieman Lab, she wrote, “Call it wishful thinking, but I see international nonprofit journalism starting to take off in 2019 the way American nonprofit news has.” Funding is even more of a challenge for international nonprofit news than it is for American nonprofit news, but TNH is seeing some success, Aly said. “Foundations that support human rights issues globally are realizing now that they can’t support human rights without somehow [addressing] all of the anti-rights messaging coming out of many corners of the world — not least the U.S.,” she said. “Thinking about the information landscape in which their work takes place is increasingly important, and I do see some openings.” TNH receives about half its funding from foundations — including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Open Society Foundations, and New Venture Fund — and about half from the government aid departments of countries like Canada, Norway, and The Netherlands.The New Humanitarian gets about 170,000 unique visitors a month, but its influence extends beyond those pageviews. Its newsletter has around 40,000 subscribers, and its Twitter account has about 85,000 followers. It sees its readership as three circles (which became more clear following a 2018 audience survey). The inner circle consists of people who are working to respond to and prevent crises: policymakers and aid workers, including UN officials at headquarters or in the field and NGO workers and executives, as well as governments providing foreign aid (“the U.S. is the biggest humanitarian donor, or was”), and the governments of countries where crises are taking place (“The foreign ministers of many African countries are loyal readers”).

Next, said Aly, are “secondary players who are starting to ask how they can be part of the solution,” including the corporate sector, human rights advocates, researchers and students, and journalists and media organizations. (TNH’s journalism has been republished by news outlets like The Guardian, the Los Angeles Times, and AllAfrica.com, as well as smaller outlets like the Yemen Times and Uganda’s Daily Monitor.)

Finally, there’s the “engaged global citizenry.” “These are people who want to donate to make the world a better place, and are trying to figure out where they should donate their money, or they’re involved in local volunteer groups in their communities,” Aly said.

Historically, TNH has reached those people through the aforementioned partnerships with mainstream media publications. Over the last year, though, the organization has made it a goal to attract them as readers directly. Last year, TNH hired Josephine Schmidt as its first-ever executive editor. Schmidt had spent the bulk of her career at The New York Times, focused on developing the paper’s international edition. When she came to Geneva, “I really saw my role as helping [TNH] to continue its transformation out of the UN,” she told me. “It’s one thing to have been, basically, an internal information center for an international NGO. It’s another thing to become a full newsroom, and an independent newsroom at that — it’s not a switch you turn on and off.” She’s focused on making TNH’s journalism more accessible and less insider-y, beefing up its appeal to that third ring of readers while ensuring that it is still useful to the people who depend on it.

“[TNH] has, for so long, been an integral part of the work done within the humanitarian sector that we’d relied on shorthand and language that, when you take it out of the UN context, is a bit mysterious and opaque,” she said. “We’re really working on becoming a bit more conversational in our language, our headlines, our text. We want to be transparent and accessible in the language and the words we use — not dumbing it down, but spelling it out a bit. We’ve also been looking very closely at how we frame our work: How we explain up front with our display type — not only our headlines — why this matters. Why does this coverage matter, not only within the humanitarian sector, but to the broader world? It’s not a difficult thing to do, but it is a matter of being more conscious.”

TNH’s 12-person team is spread across the world. Schmidt is in Geneva, along with senior editor Ben Parker. There are also editors based in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and the UK, and they work with dozens of stringers around the world. This allows TNH to publish 10 to 12 pieces online every week. “These are pieces that, for the most part, would be analogous to an enterprise piece or a magazine piece from another media organization,” Schmidt said. “They might publish them once a week or once a month, but we do at least six of them a week.”

The site also offers briefings on breaking news within the humanitarian sphere. And TNH, like any news organization, is experimenting with different ways of bringing its coverage to readers. Its webinars have been surprisingly popular: A recent one about local responders attracted more than 200 signups. TNH is also revamping its newsletters, with plans to make them topic-specific (on themes like forgotten conflicts, and the policy environment in Geneva). It is exploring topic-specific Facebook groups. “And we hope to launch a membership model as soon as the end of this year,” Aly said. “Not necessarily as a financial revenue stream — though we hope it will boost donations — but more as a way to allow to our readers to connect to each other.”

Those opportunities for connection are important — because, as Schmidt pointed out, TNH’s topic matter is often tough stuff.

“What we cover is, by definition, hard,” she said. “It’s emotionally difficult material. Someone responded to our newsletter on Twitter the other day, calling it the ‘Weekly Chronicle of Human Sadness.’ We can’t escape that.

“But what we can do is make it a bit lighter for our readers, and I don’t mean lighter in terms of humorous or levity. I mean lighter in terms of offering alternatives or a way forward. It is not anything as simple as offering them hope. It’s offering a path forward, the opportunity for some movement. We’re saying: This is the situation. These are the questions that need to be asked to move ahead. These are the needs to be addressed. We’re not simply dumping all of this information on our readers. We’re really giving them a tool to move forward and take the next step.”