Every day, readers are faced with a firehose of news online. News organizations realize this, and they’re trying a bunch of different ways to make the news more manageable — creating chatty summaries of their own stories or publishing extra mobile-friendly content like short Q&As.

Some publishers are juggling apps and newsletters. The New York Times’s popular morning and evening briefings originated on the NYT Now app, but have since been made available in other formats like the email newsletter. BuzzFeed’s news app, which launched this past June, imports features from its newsletter, and both the newsletter and app are evolving publicly on Twitter through the hashtag #teamnewsapp as well as on BuzzFeed’s blog.

Other publishers have gotten creative with newsletter strategy. Vox’s Sentences avoids the morning flood and arrives in inboxes at 8 p.m. ET. Quartz’s Daily Brief is a clean, text-driven summary of news with a few simple categories.Some publishers focus on a “finishable” experience. Yahoo News Digest is an intricately designed app that uses an algorithm and human curation to create two digests a day, one in the morning and one in the evening. The Economist’s Espresso app, the first daily product in the publication’s 172-year history, provides a “very tightly curated bundle of content” built around an even shorter reading experience of just a few minutes.

I asked these news organizations about their approaches to slimming down a day’s worth of news into manageable forms for their readers. The responses below have been condensed and edited for clarity.

Stacy-Marie Ishmael, managing editor of mobile news, and Millie Tran, editor of mobile news and the BuzzFeed News daily morning newsletter:

In the same way, everyone on #teamnewsapp contributes to the app. We all have ‘app shifts’ that include a lead editor and what we call a ‘back editor.’ The lead editor on duty is responsible for keeping the app updated, coordinating with the different BuzzFeed News desks on big and breaking stories, and deciding when and whether to send push notifications. The ‘back editor’ keeps an eye on the overall app presentation and experience, and is also responsible for pitching stories to add to the app, helping with the ‘A Bit Of Background’ snippets, and updating our timelines.

Because BuzzFeed News is a 24-hour operation, we use a system of handovers to ensure that whoever comes on duty knows what’s been happening and what’s scheduled. On #teamnewsapp, we’ve got people in New York, Los Angeles, and London, so we also use handover emails and regular messages in our internal Slack channel to alert each other to what needs monitoring and what’s been going on. Every editor ends their shift with a handover note.

Our job is to read and watch everything newsworthy on the Internet and then decide how and whether to present stories to our audience. We use Feedly, Twitter lists, and everyone’s own personal workflows for keeping an eye on what’s going on around the world. We look for items that are trustworthy, interesting, relevant, accessible — and mobile-friendly. There are about 15 to 20 pieces in the app at any time, and how often we update those really depends on the news flow. In a fast-moving news situation, we might be adding or updating elements every few minutes.

We always include a mix of formats and sources. The BuzzFeed News app natively supports embedded tweets, Vines, and GIFs, and we’ve built our own formats too, like the timelines. A key question for us is ‘will this help our audience catch up on what’s going on right now?’

The app process is not so different from what we do with the newsletter, which has some additional constraints because it’s email — but each process informs the other. With email, the formats and interactions are more limited, but those limitations help us push what we have further, and sometimes those pushes lead to new ideas for the app.

The app process is not so different from what we do with the newsletter, which has some additional constraints because it’s email — but each process informs the other. With email, the formats and interactions are more limited, but those limitations help us push what we have further, and sometimes those pushes lead to new ideas for the app.

An example is ‘Quick Things To Know,’ which is a very short and simple list of news that you don’t really need more than a headline to catch up on. It was a way for us to condense the length of our email, but still provide a lot of information to our subscribers. We’ve taken that idea and have been experimenting with similar thematic ‘quick things’ in the app. That information density is the sweet spot we’re always striving for. The email format pushes us to play and learn, then apply those lessons to other platforms.

We’ve switched on the most-requested feature, which is the ability to tap on one of the bulleted sentences in the ‘Quickly Catch Up’ section and be taken to that story. We’re working on a couple of cool features around how we present related stories and packages in the app.

Tom Standage, deputy editor of The Economist:

We try to focus on stories that are coming up that day, so we’re telling you what to expect, but we also respond to the previous day’s big stories. And sometimes Espresso stories don’t have a news peg to a particular day, but are just big issues where we want to give our view. Espresso is designed to cover the main points of the news even if you don’t read anything else, so we wouldn’t avoid a story just because others have covered it a lot; we’d look for a distinctive take to offer our readers. That said, we don’t cover celebrity news and we don’t often write about sport, but neither does The Economist’s weekly edition. That’s not what our readers expect from us.

Most days we have the same stories in the Asia, Europe, and Americas editions, but sometimes we vary it a bit, either because stories have particular resonance in one region but not in another, or for timing reasons. If there’s a big British politics story that is dominating the news agenda there but looks a bit parochial abroad, we might run that only in the European edition, and run another story in the Americas and Asia.

The content is all written internally. The longer pieces (150-word ‘chunks’) are written by our beat correspondents, the same people who write articles in the weekly. The shorter ‘gobbets’ on the ‘World In Brief’ page are written by the editors of Espresso.

We have two full-time editors on Espresso, and they are supported by the rest of the Economist’s editorial infrastructure: correspondents, the data/graphics team, the picture desk, the research/fact-checking department, and so on. We also have a rota of people in Washington, D.C., and Singapore who update it overnight, but they are drawn from the ranks of our editorial staff, rather than being dedicated to Espresso.

We insert a link or two in Espresso each day, but it’s always to background reading in The Economist. We don’t link to other sites. The idea is to maintain ‘finishability.’ If links are what you want, there’s no shortage of other things to read. There are lots of good morning-briefing emails that are stuffed with links to interesting articles, but the idea of Espresso is that once it has arrived, you can read it without having to click on links or visit other sites or wait for things to load, and then when you’ve read it, you’re up to speed.

We’ve had 900,000 app downloads. Daily reach is 100,000 and weekly reach is about 200,000. Around 300,000 existing Economist subscribers have activated access to Espresso and we’ve had more than 50,000 people try the free one-month trial. The majority of Espresso readers are existing subscribers [to The Economist] for whom this is an added benefit of their subscription, but we are reaching some new readers as well.

We’ve just done a survey of Espresso readers. We had more than 15,000 responses and more than 5,000 comments. We’re still analyzing the results, but a lot of readers would like a weekend edition. Around 30,000 people open the app each Saturday and Sunday, even though [the content isn’t refreshed then]. There were also requests for more science, culture, and sports coverage, and for audio. We’ll be taking all this into account as we continue to improve and develop Espresso.

Clifford Levy, assistant masthead editor and editorial lead of the NYT Now app:

Our briefs are all curated by a terrific team of editors, which is one of the reasons why they resonate with our readers. Currently, there are two main people focused on the morning briefing and two main people focused on the evening briefing. There are five to eight editors who run the NYT Now app, 24-7. The morning and evening briefing were developed as two of the anchors of the NYT Now app, but they’re different from the app in part because they now live on so many other platforms. We all work together to make sure they seem integrated into the app.

The stories chosen for the briefings don’t mimic the homepage. These are not news summaries. We’re conscious of short paragraphs and sentences, of what’s pleasant to read on a phone screen. For example, in the morning briefing, there are few news items that are more one or two sentences long. If you want more information, you click on the links. The number of items included in the briefing depends on the day, and there’s no hard and fast rule on that.

The focus of the morning briefing is what you need to know to begin your day. We’re looking at the stories that gained a lot of attention overnight. We’re reading a lot of the internal memos that are going around the Times newsroom to see what stories are going to be happening during the day. The Washington bureau, for instance, sends out a list at night to say, “This is what’s going to happen and this is what we’re going to be covering,” whether it’s Congress or what the president is scheduled to be doing that day. We can glean a lot from some of the internal communications going around the Times.

We feel it’s very important to have a mix of stuff in the briefing. It can’t just be hard news. We also like to have lighter items, interesting stuff that’s happening in the world of books or pop culture. Readers don’t want to be hit with only big important news; they like a whole buffet.

The last item on the morning briefing is something we call backstory, which is often very light. It’s a way to end a briefing with almost a dessert. It’s very popular with our readers.

Our evening briefing has a different framing — it considers that you may not have had a chance to check in with the news during the day. The evening briefing is much more visual, with the idea being that at the end of the day, it’s nice not to be hit by too much text. A lot of readers tell us they don’t have the time during the day to read everything. We want them to feel confident that by reading these articles, the most important events of the day are noted. The weekend briefing is also pretty visual and looks back on the week. We’ve started putting video into the evening and weekend briefings.

Each of our platforms has different abilities and different ways they render our journalism. The main New York Times app, for example, is much better at presenting photos and videos throughout an article. As we improve our briefings, we’re considering the different strengths and limitations of each platform.

Adam Pasick, breaking news editor and Daily Brief lead:

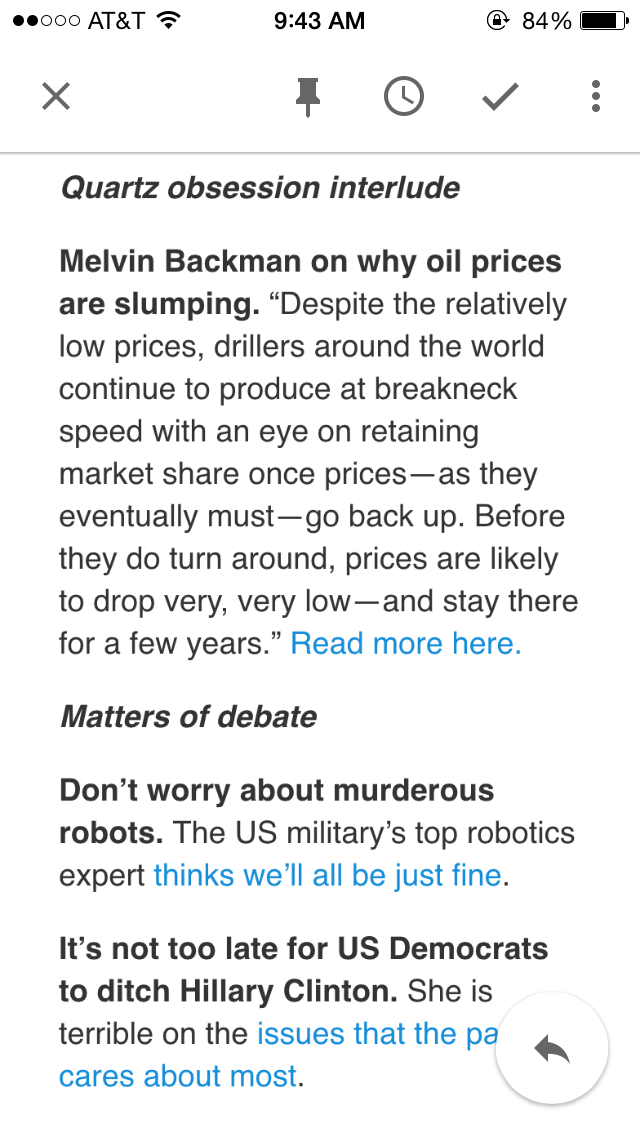

Filling in each section with the right items feels like completing a crossword puzzle. The entire format of the Daily Brief has been remarkably stable ever since Quartz was formed, and the categories [‘What to watch for today,’ ‘While you were sleeping,’ ‘Quartz obsession interlude,’ ‘Matters of Debate,’ and ‘Surprising discoveries’] were originally created by my colleagues Gideon Lichfield and Tim Fernholz.

‘Quartz obsession interlude’ is sort of our in-house long reads section. ‘Surprising discoveries’ is the news we find in the weird corners of the Internet. The hi@qz email at the end of each Brief receives everything from praise to criticism to suggested stories. As of yet, no one has sent us any ‘fountain pens and Wi-Fi allergy remedies,’ as the most recent Daily Brief requested.

There are three writers and three editors working on the three editions scattered across the U.S., China, and U.K. Each edition iterates from the previous one, so it’s a rolling, 24-hour process. It’s quite a substantial investment in time and effort, but we have been encouraged by the reaction from our readers and ad sales team. We’re always trying to find little ways to make our lives easier. Slack, WordPress, and MailChimp all play a role in our workflow. Lately we’ve been playing around with the entire team writing and editing within the same Google Doc.

We have three daily editions, but we are constantly finding and writing new items. Currently those feed our homepage, and we are always thinking about other platforms where they could end up.

We have three daily editions, but we are constantly finding and writing new items. Currently those feed our homepage, and we are always thinking about other platforms where they could end up.

There are a few quantitative limits to what we include in the Brief. The ‘While you were sleeping’ section is taken quite literally, so the news can’t be more than about 12 hours old, but mostly it’s done subjectively. We try to find the stories that reside at the intersection of interesting and important, just as with the rest of Quartz. We don’t optimize for sending traffic back to Quartz, so the links are chosen from the best coverage on a given story, no matter who wrote it.

We don’t break our subscribers down by edition, but the Americas Brief is the largest one. According to our user surveys, nearly half of subscribers are ‘senior management’ or above. We recently crossed the 150,000 mark for subscribers globally, and have maintained an admirably high open rate. That tells me that we are providing a valuable service, not one that languishes in the ‘unread’ section for all eternity. Which is good, because the Daily Brief is a lot of work, and it would suck if it was wasted!

Dylan Matthews, Vox.com senior correspondent:

‘Verbatim’ isn’t organized around a theme, but includes important quotes. ‘Miscellaneous’ is just important stories I find that are not related to the main topics of the day. Then Dara and I talk about what the top three stories should be, and she has primary responsibility over the top three sections.

We write the material in a spreadsheet. Now we just have a column for the URL and a column for the source, and it’s great. It used to be that I was manually writing tags in a Google Doc. (There was a point early on where we embedded links in our sentences and didn’t give the source. We got feedback from a ton of readers who said, ‘No, I already read the news, some of these stories I’ve read before.’ Because of the way Sailthru does links, it’s hard to tell where it’s going to redirect you.) All these little mundanities end up taking a lot of time!

In terms of finding articles to include in the sections, obviously if there’s big coverage in Vox, we’ll try to incorporate that. But I also want to be sure that Sentences is not just a promotional tool for us. I wouldn’t want to have a section of purely Vox articles. Because a lot of the stories we include are global, I tend to go to news organizations that I know have a large global presence and have correspondents on the ground. I always start looking at The New York Times. For European stories, especially during the Greek crisis, I used The Financial Times a lot. Reuters often does very good work on Africa stories. It all depends on the topic.

When there’s a lot of coverage around the same news item, I generally try to go to the source that has the most detail. All the stories look very similar, but when you get into the daily habit of reading everyone’s stories on the same topic, the Times, for instance, might have an interesting, crucial detail that The Wall Street Journal doesn’t, and vice versa.

Sentences goes out at 8 p.m. If news breaks at 8:30 p.m., it sucks, but there’s not much we can do about it. If it’s a really huge breaking story, we’ll write articles for Vox.com about it. If something breaks at 7:30 p.m., we might come back from dinner and use the 30 minutes to put a section together.

We’ve thought about the p.m. mailing a lot. We’ve done six or seven A/B tests where some people get our email at 6 a.m. and some get it at 8 p.m., and consistently, people open it more at 8 p.m. The flip side of that is, we’re running that test against a population that has selected an evening newsletter. The fact that most very successful newsletters are in the morning is strong circumstantial evidence. It’s something that we still think about. We wonder if there’s some way to personalize it, let people choose the time they receive it.Hailey Persinger, editor of Yahoo News Digest:

Often, the algorithm will give us something it thinks is going to become a big deal. It’s our job to figure out how to marry what the algorithm has given us with what’s actually happening. Most recently, our algorithm picked up a story about whiskey being delivered to the International Space Station, hours before I saw it anywhere else.

We try to stick with seven or eight stories in the digest, though at times we’ve had up to 11. We can’t control the news cycle. But if, say, we included a review of Straight Outta Compton and something else had broken that day, we probably would kick off the review, because we have to give the right weight to certain stories. We can’t just keep certain stories because we’ve decided that we need an entertainment story. On a regular day, though, we try to balance those categories.

Since we prepare two digests a day, if a big story breaks after the digest has gone out, our editors need to decide if they’re going to add the story. Since we have plenty of users on the West Coast, we might update the digest until about 11 or 11:30 a.m. because it’s only 8:30 a.m. in California. We want to give someone on the other coast the same breaking news thoughtfulness that we’re giving to people in our own time zone. For something big and breaking later in the day, we’ll track it and might wait to give readers instead a story that includes some deeper analysis of what it means.

We have to focus on getting the right amount of information to readers, because this is a mobile product. We try to steer away from stories with anecdotal leads. Long reads do work on mobile, but long reads don’t necessarily work in this mobile product. We didn’t tell users they were going to be reading a 6,000-word story on a Monday morning, so it wouldn’t be fair of us to make them do it.

With the homepage for any news outlet, you’re trying to keep people on the page by getting them to click on stories, slideshows, and other items. With the app, we want to get people in and out quickly. We’re not eschewing the homepage, but we don’t want to recreate it. We want to turn the app into a habit for people.