When Kevin Necessary read a story from WCPO — a Scripps-owned television station in Cincinnati with a robust website — that shared intimate details about undocumented immigrant families living in the greater Cincinnati area, he recognized something about the photos.

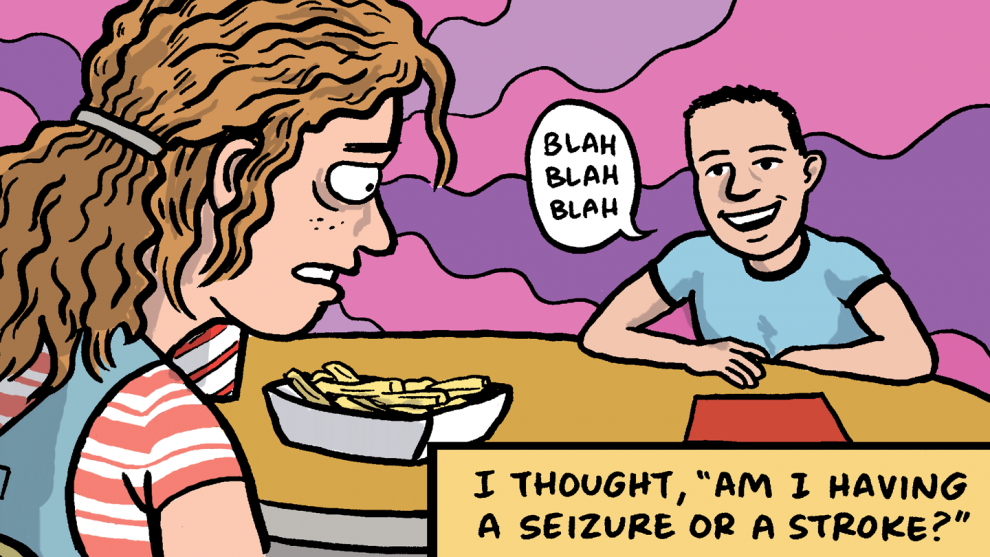

“Lucy May [the reporter] couldn’t include any kind of art other than pictures of apartments, or the back of someone’s heads or their shoulders. Nothing that would identify them,” Necessary recalled. “That really got me thinking — when we did another story of a similarly sensitive nature, could we do it as a graphic novel? Lucy had a similar idea.”

Necessary wasn’t yet working full time at WCPO, but he and May began reporting together on the gradual recovery of a family of six children, from three different fathers, whose mother was a heroin addict (May had already been working on the background of the story for a while) — talking to case workers, interviewing the families, observing court hearings to understand the legal processes at work. May took notes, and Necessary took notes and made sketches, paying extra attention to visual details. They drafted a ten-page narrative, and from there, “it was draw, draw, draw,” Necessary said: “I spent two weeks straight doing nothing but drawing.”

The result was a six-chapter graphic novel, published online at WCPO.com the day before Necessary joined the WCPO newsroom as permanent staff.

“This was my first attempt at longform narrative comics journalism,” he said. “I was a little afraid someone was going to come up to me and ask: This first piece went viral, what’s next? It’s why at nine o’clock at night I’m emailing Lucy with the germ of another idea, for what could be our next project. It’s why I went straight into working on a video explainer with another reporter, while I’m also thinking about my cartoons for the week.”

Necessary acknowledges that he’s in an enviable, and unusual, position — a staff editorial cartoonist at a regionally focused news organization for which the corporate ownership has decided to invest heavily in building out the digital side. He’s been averaging three cartoons a week (one a caption contest), and illustrates other projects, like this animated explainer on coal ash, a piece otherwise dense with scientific jargon.

Full-time newspaper editorial cartoonists are downright endangered — fewer than 40 at American dailies, according to one estimate I kept hearing repeated, down from fewer than 90 in the early 2000s and an estimated 200 in the early 1990s. (And down from around 2,000 at the beginning of the 20th century, when there were way more newspapers in business, but that’s another story.) Diversity among that small sliver is virtually nonexistent.

This narrative of decline may be a hard truth of the modern newspaper world, but it also excludes those whose visual work extends beyond commentary and satire in panel form — those who are trying to make it work as freelancers, those distributing their work on new platforms, those stretching the form in more traditional environments, and all the other circles in the messy Venn diagram of illustrators and journalism.

Jen Sorensen has worn just about every hat in the industry, editing for Fusion and freelancing for print and online publications. Joe Hoffecker has been cartooning for decades — but his primary job is serving as the audience development director for the Cincinnati Business Courier, and he generally draws one cartoon each week for the Courier and another for the nationally-oriented Sports Business Journal.

Matt Bors edits the popular comics site The Nib, which started at Medium, and last month relaunched with (and supported by) First Look Media, publishing political cartoons, nonfiction comics, graphic journalism, and experimenting with formats in between. The image-heavy site is built mobile-first (so comics panels shuffle properly), and its daily newsletter assumes that the homepage, however mobile-friendly, might not often be a direct destination for most readers anyway.

Matt Bors edits the popular comics site The Nib, which started at Medium, and last month relaunched with (and supported by) First Look Media, publishing political cartoons, nonfiction comics, graphic journalism, and experimenting with formats in between. The image-heavy site is built mobile-first (so comics panels shuffle properly), and its daily newsletter assumes that the homepage, however mobile-friendly, might not often be a direct destination for most readers anyway.

“Everything from animation to print are part of our plans right now,” Bors said. “For our relaunch, we create a giant oversized print newspaper around election material, because why not? We’re starting to think about how our work could translate to video and we’re about to drop our 2017 calendar of obscure holidays.”

Susie Cagle, who emphasizes that she’s a reporter and writer who also draws, started her journalism career blogging for Curbed in San Francisco. Her body of work explains why she’s protective of her role as a journalist “who also draws”: For Curbed (now owned by Vox Media), she reported, wrote, and illustrated a feature on house flipping and gentrification in Oakland. For ProPublica, she worked with reporters Ginger Thompson and Lena Groeger on a comic on narco-terrorism cases.

It was only after Cagle was laid off from a writing job that she really began to blend her art and writing, a move that was partly strategic. Despite the dwindling of staff editorial cartoonist positions, “I just thought, there’s no way that art and news in this way has to die. Something else has to come up. And nothing else was coming up, nothing else was bubbling up,” she said earlier this year on the Longform podcast.

“It feels like this huge bet that I took in 2008 when I lost my journalism writing job and figured that news was poised to turn more picture-heavy is finally beginning to pay off,” Cagle told me in an email. “I’m cautiously optimistic about where this is headed — I haven’t had an editor reject a pitch based on ‘but it’s…cartoons?’ in over two years.

“But I can’t say that I look to outlets to drive this — I think they’re responding to the available talent pool that’s been coming up with more of this work in recent years, and it’s still perceived as a kind of experimental one-off to take a risk on periodically, but not something worth serious and continued investment,” she added. (Since she usually works with editors more familiar with editing text than illustrations, she often ends up working very independently.) “I’d love to see more art directors on staff — how antiquated, I know! — as well as artists who write and writers who draw. When you have all that new visual thinking happening outside of your newsroom staff because someone who does both words and pictures doesn’t fit into old job descriptions, even in an era of Snapchat editors, you lose out on a lot of learning by proxy on all sides, which is just so unfortunate.”

“There is something fun and satisfying about getting out in the real world and reporting on things, rather than sitting behind your drawing table just thinking about the world, reading Twitter,” Sorensen said. “I like to get out there sometimes. It’s not something you can do all the time. I guess a few people do make a living doing comic journalism full time, but it can be involved — both expensive and time consuming.”

Sorensen also pointed out a growing space for comics that fall just outside of what might be considered “hard, graphic journalism,” including a comic she drew for Fusion, retelling anonymously a story her friend told her about being drugged and raped back in college decades ago.

“We couldn’t specifically name who her assailant was. So we just told her story,” Sorensen said. “I did have to be meticulous about it and make sure I got the facts right and was quoting her correctly. I would say that was a journalistic effort, but it’s a little different from, say, when we had someone go out and report on the California marijuana industry.”

Today’s digital and distributed media world has its own wants and needs, but many of the cartoonists and illustrators I talked to over the course of the past few weeks were cautiously optimistic that their medium could serve as an antidote to clickbait, draw new audiences, or even help shape how newsrooms approach predominantly visual platforms like Snapchat and Instagram.

Bors was blunt in his assessment: “You have to publish on a mind-numbing number of platforms and go where readers are now, namely social media platforms,” he said. “It’s a double-edged sword working with these companies, whose values are in the billions from all our free labor, but you can’t ignore them either. Thankfully, comics do well online, where the media has become a sea of garbage content and rewritten posts from other sources.”

If Facebook is going to privilege video, and if many news organizations are rushing out imperfect videos, reasoned Detroit Free Press cartoonist Mike Thompson, then animating cartoons offers one way to cut through the noise on that platform. (Plus, who doesn’t love a good GIF?) Instagram’s new Stories feature (or Snapchat ripoff), too, now easily accommodates a multi-panel narrative comic, where previously a series of images might get scrambled by its newish algorithm-driven feed.

“We’re a visually oriented society. Look at the popularity of this type of work and other forms of mass communication. Look at the movies — Disney, Pixar, the Marvel superhero franchise is tearing up the box office. The Walking Dead — based on a graphic novel. Graphic novels are all the rage right now,” Thompson, who’s been cartooning for 27 years, said. “There’s no reason the newspaper industry can’t be tapping into some of the same market.”

As was the case with WCPO’s Necessary or Fusion’s Sorensen, drawing opened up for Thompson the possibility of covering a sensitive topic intimately, without giving away identities. For a piece on sex trafficking, Thompson reported out a story himself, attending conferences, traveling around the state interviewing survivors of sex trafficking and people working on the problem. Their voices are used in the final nine-minute animated documentary, which also ran in print.

Animation is on many cartoonists’ minds. “The big changes, I would say, are how we’re starting to look at being able to tell the same information in realistically a longer form, and possibly with animation,” Chris Weyant, New Yorker cartoonist (and 2016 Nieman Fellow), said. But within political cartooning, that potential still feels largely untapped. “I feel like we’re getting on that path of discovering what we could do. For political cartoons, you want immediacy and brevity — it’s hard to find that same punch in a sequential narrative. Is there a way for me to use an animation, use a longer narrative, yet still pack that hard punch of a political cartoon?”

“In a funny way, sometimes I think I’m being hired not just as the cartoonist, but also as the social media element,” said Liza Donnelly, whose credits include, among other publications, The New Yorker. Conventional social media wisdom recommends tweeting and Facebook posting with images for more shares, more likes — a natural extension of Donnelly’s normal workflow. In addition to selling “regular” cartoons, Donnelly live-draws — sketching quick impressions at a live event and posting immediately to social media — and was on-the-ground at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia for CBS’s morning show as well as newyorker.com. She’s been at the Oscars with press credentials, live sketching the awards. During the New York primaries, an NBC News reporter contacted Donnelly to Snapchat her live-drawing the returns:

Follow us on @Snapchat to see @lizadonnelly live cartoon the #NYPrimary results #Decision2016 pic.twitter.com/w8GRSvlcC6

— NBC News (@NBCNews) April 20, 2016

Standing room only! #DemsInPhilly @CBSThisMorning pic.twitter.com/cnkUKBuerh

— Liza Donnelly (@lizadonnelly) July 28, 2016

“She told me, ‘We want to get young people to be interested in the news, and one way to maybe do that is through cartoons and sketches,'” Donnelly said. “Jon Stewart’s humor brought people into the real news, and maybe cartoons could do the same.”

“The news cycle has accelerated as well, so the shelf life of many cartoons is quite brief,” Dan Wasserman, editorial cartoonist for The Boston Globe, said, recalling a time in his three-decade career when he distributed his syndicated cartoons on paper, via snail mail. Wasserman, too, live-sketched the conventions using his tablet.

“They are real-time reactions that are done, concept to online posting, in less than 10 minutes. I get immediate feedback through social media,” he said. “It’s much more of a graphics-based conversation with a live audience, very different in character from the relationship with print readers.”

Many described how their cartooning style has become simpler, infused with an awareness of how and where readers are viewing their work (on mobile, through social). (Practical considerations, too, are at play, for cartoonists working online, publishing on sites where the majority of readers are visiting via their phones: breaking up comics into multiple panels so they stack vertically whenever possible, or making sure the text is legible on small screens.)

“I feel like my comic process is constantly changing every year due to my current social media preference — which wasn’t the case in college when I based my page layouts on how I would print my work as a minicomic,” cartoonist Kat Fajardo told me in an email. “Now that I share most of my comics online, I have to be mindful of verticality since I tend to post pages individually for easy reading. I feel like both my style and comic format is much simpler after years of posting work online.”

But cartoonists I talked to were careful to neither credit social media with too much, nor blame it for its influence. “I enjoy doing multi-panel cartoons, but I also know that most people want to share, like, and move on,” Necessary said. “There were times I might spend hours drawing one cartoon. But who am I really doing that for? I’m doing that just for me, because I like elaborate cartoons where the perspective is perfect and everything looks great, making sure all the lines converge correctly. Would it be better if I simplified it to a more easily, more quickly read image?”

“Shareability really is a thing you have to consider,” Sorensen said. “I would say that one big change with working digitally is the sense of what is shareable and what is not. Sometimes you defer to that. Sometimes that influences what you do, and sometimes you decide, this might not be popular, people aren’t talking about it, but it should be seeing the light of day. That awareness has changed.”

For local outlets, the idea that something less buzzy should still see the light of day is critical (though in some cases, in a small market, this might mean totally unintentional, very similar cartoon commentary on the same issue).

“We’re in the swing county of a swing state, and a lot of cartoonists are doing the big national issues — Trump, Clinton. Or the Orlando shootings, the Paris attacks. I’ll do those too,” Necessary said. “But I’m doing many more local cartoons so that I can build a local audience. I could do a cartoon on Donald Trump every day. That man is cartoon fodder. But that’s not where my priorities should be. I might do something about the budget in Cincinnati City Hall or something wonky that might not get a lot of shares. Not every cartoon needs to go viral.”