After weeks of criticism over its role in spreading fake news during and after the 2016 presidential election, Facebook announced Thursday that it’s taking some concrete steps to halt the sharing of hoaxes on its platform.

We’ve focused our efforts on the worst of the worst, on the clear hoaxes spread by spammers for their own gain,” Adam Mosseri, Facebook’s VP of product management for News Feed, wrote in a blog post. He described the updates to Facebook’s platform as “tests,” and stressed that these are “just some of the first steps we’re taking.”The tests are confined to a small percentage of U.S.-based, English-language users for now and are in place on both desktop and mobile (again, since they are being tested, you may not see them — you could always use the tool Slate launched this week).

Facebook’s outlined changes are similar to those floated by CEO Mark Zuckerberg in a post last month.

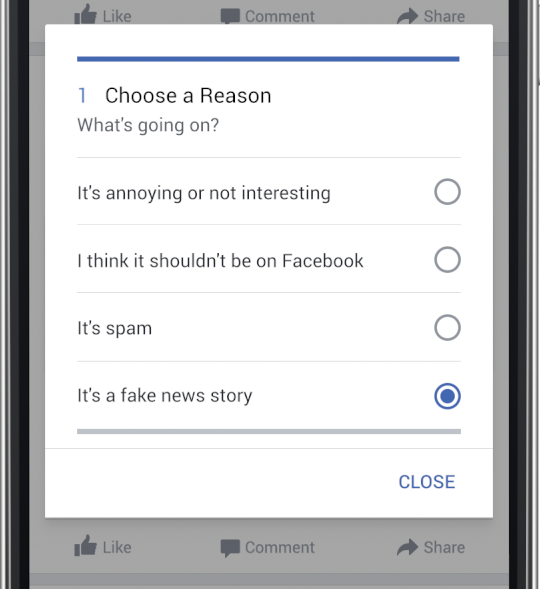

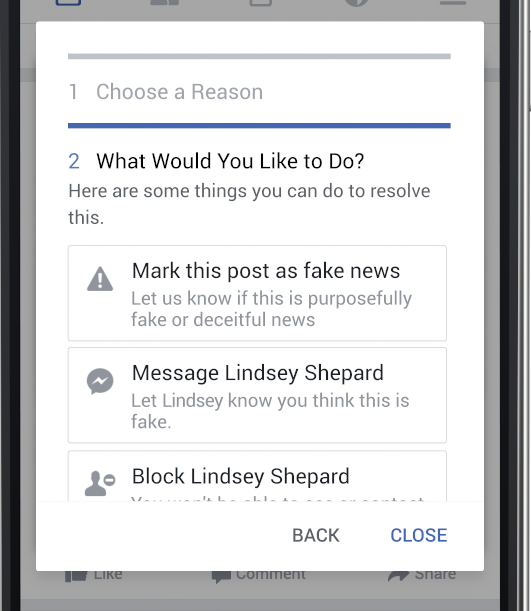

Users will be able to mark stories as fake by clicking on the existing “Report Post” option that appears in a (not-very-prominent) dropdown menu in the corner of each Facebook post and selecting the new “It’s a fake news story.” They then have to take a second step of, again, marking it as fake.

Once a story has been flagged as fake, the most complex element of the new strategy begins. A Facebook spokesperson walked me through how the fact-checking process will work. Facebook is working with, to start, a handful of third-party, U.S.-based fact-checking organizations: ABC News, Snopes, PolitiFact, FactCheck.org, and AP. (The sites are part of Poynter’s International Fact Checking Network and have agreed to a “fact-checkers’ code of principles.”)

Because the group of third-party fact-checkers is small at launch, and as part of its effort to focus on the highest-impact “worst of the worst,” Facebook is doing some sorting before the reported stories go to the fact-checkers. Its algorithm will look at whether a large number of people are reporting a particular article, whether or not the article is going viral, and whether the article has a high rate of shares. Facebook has also already had a system in place, for about a year, that uses signals around content (such as how people are responding to it in comments) to determine whether that content is a hoax.

In combination, these inputs create an algorithm-vetted set of links that then goes on to a team of researchers within Facebook. This team assesses the links on the domain level to determine that the news comes from a news source (or a site portraying itself as a news source) and that it is not a personal post.

Finally, the links are sent into a dashboard that the four fact-checking organizations have access to. Representatives from the organizations fact-check the links, and if the stories are false, they add a link that debunks the story. (The way that the system is set up requires the fact-checkers to have a published article that debunks the story; they can’t simply mark a story as fake with no source.)

The fact-checkers’ actions result in stories being marked with red warnings showing that they’ve been disputed. When a user clicks, he or she can learn more or can go on to see the debunking link. From Facebook:

It will still be possible to share these stories, but you will see a warning that the story has been disputed as you share. Once a story is flagged, it can’t be made into an ad and promoted, either.

Facebook is also adjusting its News Feed algorithm. Disputed stories will appear lower in the feed, but also:

We’ve found that if reading an article makes people significantly less likely to share it, that may be a sign that a story has misled people in some way. We’re going to test incorporating this signal into ranking, specifically for articles that are outliers, where people who read the article are significantly less likely to share it.

Of course, Facebook users frequently share articles without having read them fully or at all.

Finally, Facebook is “disrupting financial incentives for spammers.” Last month, Facebook banned fake news sites from using its ad service. On Thursday, it said it’s gone further:We’ve found that a lot of fake news is financially motivated. Spammers make money by masquerading as well-known news organizations, and posting hoaxes that get people to visit to their sites, which are often mostly ads. So we’re doing several things to reduce the financial incentives. On the buying side we’ve eliminated the ability to spoof domains, which will reduce the prevalence of sites that pretend to be real publications. On the publisher side, we are analyzing publisher sites to detect where policy enforcement actions might be necessary.

The company wouldn’t elaborate on the types of policy enforcement actions it might take — though it certainly has the ability to pull down publisher pages completely.

The key issue and possible pain point, which isn’t addressed in the changes Facebook outlined Thursday, is that reporting happens on a per-post level, rather than on the publisher level. Since Facebook is focusing specifically on “clear hoaxes spread by spammers” here, it seems as if it would be more efficient to simply block known hoax news sites like The Denver Guardian. But that seems to be more of a blanket approach than Facebook is willing to take at this point, and it would likely open the company up to a great deal of backlash.

Facebook may be figuring that a story-level reporting system, rather than a publisher-level reporting system, is less vulnerable to mass attacks from partisan groups. Still, it seems likely that people who want to coordinate to mess with the system will be able to do so fairly easily: A group of Trump supporters could mobilize to flag all CNN stories as fake, or where a group of Clinton supporters could report all Breitbart stories as fake.

“We believe in giving people a voice and that we cannot become arbiters of truth ourselves,” Masseri wrote, “so we’re approaching this problem carefully.”