Over the weekend, I was chatting on Twitter about last week’s media flare-up, l’affaire Manjoo. That’s the debate prompted by New York Times tech columnist Farhad Manjoo writing this piece, headlined: “For Two Months, I Got My News From Print Newspapers. Here’s What I Learned.” It was only the latest in the overstuffed genre of people recording their retreats from technology and news. They usually end with a gleeful report of the results, tossing aside their Klonopins like a congregant’s crutches at a scam preacher’s Sunday show.

(The Sunday Times even featured another candidate for this particular canon, Sam Dolnick’s story of a former top Nike executive who, wealthy enough to rely on a distant financial advisor to handle his riches, has moved to Ohio and decided to ignore all news of the outside world. This guy, basically, but forever.)

From Manjoo’s piece:

This [being intentionally ignorant of real-time news] has been my life for nearly two months. In January, after the breaking-newsiest year in recent memory, I decided to travel back in time. I turned off my digital news notifications, unplugged from Twitter and other social networks, and subscribed to home delivery of three print newspapers — The Times, The Wall Street Journal and my local paper, The San Francisco Chronicle — plus a weekly newsmagazine, The Economist.

I have spent most days since then getting the news mainly from print, though my self-imposed asceticism allowed for podcasts, email newsletters and long-form nonfiction (books and magazine articles). Basically, I was trying to slow-jam the news — I still wanted to be informed, but was looking to formats that prized depth and accuracy over speed.

I happen to think there’s an awful lot to be learned from both digital detoxing and news avoidance. But the #takes took a turn Friday when this CJR piece by Dan Mitchell was published.

But he didn’t really unplug from social media at all. The evidence is right there in his Twitter feed, just below where he tweeted out his column: Manjoo remained a daily, active Twitter user throughout the two months he claims to have gone cold turkey, tweeting many hundreds of times, perhaps more than 1,000. In an email interview on Thursday, he stuck to his story, essentially arguing that the gist of what he wrote remains true, despite the tweets throughout his self-imposed hiatus.

It seems likely that Manjoo isn’t lying, and that he really believes he had unplugged, and really believes that his weak-sauce explanations don’t belie the point of his column. It could be that Manjoo’s column really does serve as a warning about the pernicious effects of social media. Just not in the way he meant it.

Tweets fired!

Anyway, back to this weekend: My friend Michael Young (an ex-Timesman himself, now CTO of Digg) mentioned that he’d pulled Manjoo’s Twitter activity via API:

i was curious and took a peek w/ the twitter api. "unplugged from twitter" is > 1k tweets *and* 1k likes.

— Michael Young (@myoung) March 10, 2018

So naturally, a data viz project was born:

Seems like we need a data visualization showing all the times of usage, combining tweets and likes! (Actually, can you email me that api output?)

— Joshua Benton (@jbenton) March 10, 2018

I was curious what “unplugging” from Twitter looked like for someone like Manjoo — which, let’s be honest, is a lot like saying “someone like me” or “someone like most Nieman Lab readers.”

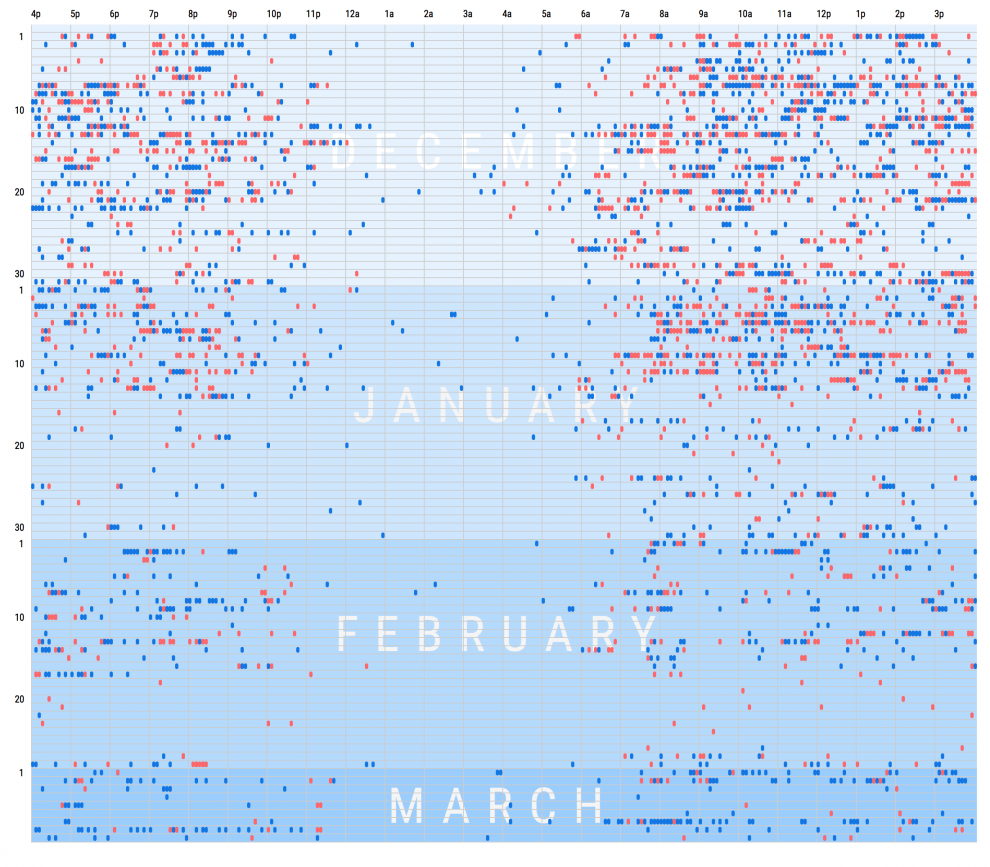

Michael emailed me the API output, I spent some time googling Excel functions and building the poorest man’s D3.js from memory, and this is the result: a graphical representation of Farhad Manjoo’s Twitter activity from December 1 (before his “unplugging” — think of it as the control sample) through to Friday.

One quick explanatory note: Twitter’s timestamps are in UTC, which was 8 hours ahead of Manjoo’s Bay Area home base during this time. (It’s actually only 7 hours ahead as of yesterday — thanks, Daylight Saving Time.) So instead of the native tweet times, I’ve put the Pacific Time equivalent in the labels atop the chart. That means the leftmost parts of this chart are actually from 4 p.m. PST the day before what’s listed. Anyway, not particularly important, but the underpopulated areas in the middle of each day (UTC time) in the chart are, as you would expect, the West Coast overnight.

What are all those blue and red marks? Each location you see in each row represents a five-minute stretch of time — for example, the first one on the left represents 4:00 p.m. to 4:05 p.m. There are 12 of these periods in each hour and 288 in each day.

If there’s a red mark, that means Manjoo tweeted at least once in that five-minute period. If there’s a blue mark, that means he liked a tweet in that five-minute period. (Of course, he both tweeted and liked tweets during some of these periods — the color of the mark matches whatever he did last.)

A few observations:

Holy moly, he was on Twitter a lot. Take a look at December. From my quick count, between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. that month, there were only 32 complete hours where he wasn’t using Twitter. That’s out of a total of 248 — and that’s counting weekends and during the holidays. (And of course, he might have just been reading Twitter during those, not tweeting or liking.)

It’s not hard to see why he might find a detox appealing. But then again, how many journalists do you know whose chart would look pretty similar? (Please no one do this for me — I’m scared to think about the result.) The appeal of Twitter for reporters is well known, but it’s worth spelling out: The benefits we get from it, real as they are, come at the cost of constant partial attention, all day and all night.

This detox wasn’t a New Year’s resolution. January 1 comes and goes without any substantial change of behavior. The effort seems to kick in on January 15.

He never completely “unplugged from Twitter,” but he came close at times. The CJR piece is correct to say that this was hardly a two-month silent meditation retreat. He either tweeted or liked a tweet every single day of this span — with just one exception, February 25, which I assume he spent reading nine books, running a marathon, and composing a symphony. And there are some days when his Twitter activity looks pretty indistinguishable from his 2017 pace.

That said — I should note that 125 of the 2,706 tweets he posted during this period were sent from Nuzzel, the app that sifts through your Twitter stream and identifies the links being shared most. It’s the nicotine patch of a Twitter detox, letting you get a taste of what’s being discussed without all the manic scrolling. (It’s great; I use it every day.) Between February 18 and 26, 15 of his 21 tweets were sent from Nuzzel, which indicates he really was taking things seriously for that stretch.

Of course, one nearly Twitter-free week is not the same thing as “nearly two months.” But there are periods when his activity really did scale back substantially, especially during evening hours. (The occasional work-hours peek at Twitter is perhaps justifiable for, you know, a technology columnist — if not for someone writing a stunt piece like this one.)

Likes are the real measure of Twitter time-wasting, not tweets. For a 21st-century technology journalist, you could argue not tweeting out your stories borders on malpractice; Manjoo has more than 160,000 followers, and it makes sense to use that marketing tool. But tweeting out a link once or twice isn’t equivalent to hours of mindless scrolling. If you’re liking lots of tweets, that means you’re reading lots of tweets — and that means your time and attention probably aren’t optimally allocated.

(I recently lamented the breaking of Wren, a very basic Mac Twitter app that only let you tweet — not read. “Intentional tweeting starts here,” their slogan went. It fell victim to a Twitter API change the developers didn’t feel like dealing with — someone out there please rebuild it.)

So here are Manjoo’s tweets and likes, separated out. First, likes:

And now tweets:

The changes in the second halves of January and February become more clear when you look at it this way. And while he’s not abstaining, exactly, it’s also not hard to see how this sort of a cutback would bring the sort of significant benefits his piece claims.

So what should we take away from this, perhaps the single most obsessive analysis of one man’s social media behavior since every piece on @realDonaldTrump?

— To say Manjoo “unplugged from Twitter” really isn’t accurate. A Times spokesperson told CJR “the paper doesn’t view his assertion as a falsehood, and won’t be issuing a correction.” That’s more weasely than the Times’ standards should allow. A clarification, an update — it is worth something to let readers know that what the piece leads them to believe isn’t true. This ain’t exactly Jayson Blair, but promoting clarity is a good practice nonetheless.

— It really is amazing how much of our time we give to this social network we don’t control. I love Twitter; it’s been very good to me and to Nieman Lab, and no other news product is a better instantiation of all the buzzing preferences inside my head than the feed I’ve been building for almost 12 years. (I’m certainly aware that as a white guy, I don’t face even 1 percent of the abuse and trolling that others do.) But when I think of all the energy I’ve poured into 140 or 280 characters over that span, it’s not hard to think I should’ve been going to the gym instead.

— How we construct our digital environment can have a big impact on our behavior. Moving from Twitter to Nuzzel, as Manjoo did for stretches, is a concrete step that lets you get much of the benefit in a fraction of the time. We should all be looking for ways to take that same sort of step.

I used to have Tweetbot open and visible on my iMac screen all damned day. It was like taking the SAT with a marching band high-stepping around your seat — a built-in distraction. I quit that for good last year, forcing myself to go to twitter.com in a browser when I have a critical bon mot to share. That’s better — but it’s also still easy to be seduced by that Notifications badge at top left, or the “In case you missed it” section algorithmically designed to pull you back in, Michael Corleone style.

So while I was doing this dumb data viz, I decided to go a step further — installing a Chrome extension that lets me block twitter.com. I plan to use it when I really need to get some writing done or need to focus for an extended period. (It’s on now as I type this.)

Maybe it’s deleting the Twitter app from your phone; maybe it’s just turning off notifications. Or maybe your current level of social media interaction is exactly what’s right for you! (No judgment here.) But I think the one good thing l’affaire Manjoo has given us is the opportunity to think about the current slicing of our attention and how the built environments of our screens impact it. That’s something to tweet about.