What probably won’t end with the election, though, is the collective, infinite screams of “fake news” and finger pointing from all sides. (The Paris prosecutor’s office saidon Thursday it was opening a probe into whether fake news stories were being spread in order to influence voters in Sunday’s election. Spoiler alert: They were.)

CrossCheck, the France-wide, bilingual fact-checking collaboration with 37 newsroom partners checking (and cross-checking for each other) audience questions, is wrapping up its 10-week sprint after debunking around 60 reader-submitted questionable stories (it received around 500 questions total through its submission form). Throughout the process, CrossCheck accumulated a lot of data on reader reactions and social engagement, and it’s now figuring out how to conduct useful research based on what it’s collected, Claire Wardle, director of research and strategy at the Google News Lab-supported First Draft News, and Sam Dubberley, CrossCheck’s managing editor, both told me. The team is now talking to Lisa Fazio, a social psychologist at Vanderbilt University, and has also applied for Knight Foundation money to run studies around the questions that arose during the fact-checking period. How did the way debunking headlines were worded change readers’ responses? What about the use of visuals? Importantly, did having multiple newsrooms — and multiple logos appended to each fact check — actually increase readers’ trust in the information? Or did it feed into the narrative of an out-of-touch media elite, huddling together? (“We did get people who asked, ‘Who’s behind you?’ ‘Who’s funding you?'” Wardle said.)

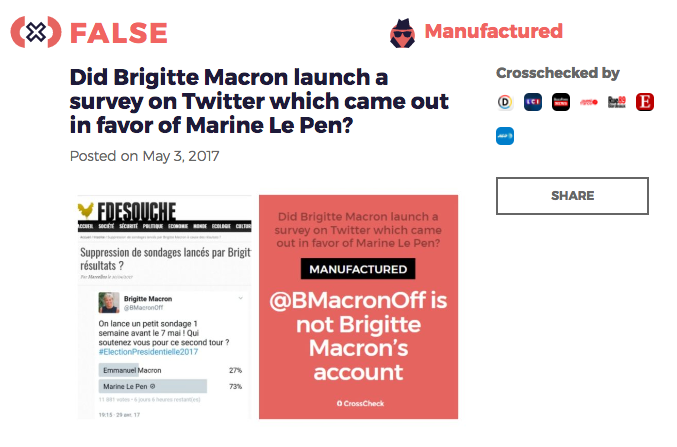

The CrossCheck fact-checking process itself was well oiled: A partner news organization would claim a submitted question to debunk in the team Slack, and other organizations could debate and request elaboration. If they agreed with the fact check, news organizations could add their logos to the debunking writeup. (Additionally, journalism students served as liaisons between all the newsrooms and the CrossCheck team.) Did Emmanuel Macron’s wife Brigitte really launch a Twitter poll that turned out in favor of Le Pen? No. Was Macron really caught on video washing his hands after shaking hands with workers? Also no.

“It’s become clear during this project that as a news industry, we have never had to deal with telling stories about rumors and false content at the level we had to do now,” Wardle said. Certain fake news sites achieved a remarkable level of sophistication: One imposter site mimicking the French-language Belgian site Le Soir even included real links that led back to the real Le Soir website.

The team also had to manage concerns around fueling misinformation through fact-checking it. It realized, for instance, that in including false imagery to illustrate the fact-checks themselves, it was helping recirculate misinformation on social; AFP, a CrossCheck partner organization, helped design a different social card that could be shared on Facebook and Twitter, that immediately made clear the story in question was false. Then there was the concern about creating greater visibility for stories that might have had little staying power.

“If we were to debunk a story too early, when it was just sitting around in very niche Facebook groups, then we were going to be giving it oxygen. But if we let rumors go too far then it would take hold, and it would have gone too far to take it back,” Wardle said. “Some people say, ‘Hey, you guys only debunked 60 stories?’ I thought in two months, we’d be able to do maybe 10! And part of that is our responsibility to audiences — helping them navigate a complex information ecosystem, and not to amplify rumors.”

Facebook didn’t offer additional insights beyond the usual audience metrics everyone gets, and CrossCheck just missed the timing for Facebook’s fake news initiative that rolled out in France (where debunked stories started getting tagged, with links to debunking articles). But Facebook did offer free promotion, which helped fact-checked stories reach an audience beyond the readers of the partner news organizations (on Facebook, CrossCheck hit more than 180,000 followers over the 10 weeks). The team created several video explainers as well, knowing they would do better in the social environment.

Both Wardle and Dubberley are measured about what’s next, beyond the need for additional research.

“To say CrossCheck is the solution after doing this for one election, that this is exactly the model, that this is perfect… it’d be showing a lot of hubris to say ‘everybody should now do CrossCheck’ without doing the proper social science research based on the data,” Dubberley said. Wardle said the team’s heard from countries from Korea to Kenya about setting up a similar initiative around elections. “People have asked, ‘Will you come to our country? We really need it.’ Well, I don’t think we know yet whether we need it or not, or whether we need it in this way. We don’t know the impact we’ve had without more research, and we don’t know if having organizations work together reinforces the idea that media is one big plot? We don’t know yet.”

“I really felt like we needed to put something into the field, being clear what we were working on was a sort of laboratory,” Wardle added. “If we didn’t put something into practice, we wouldn’t have anything to test.”