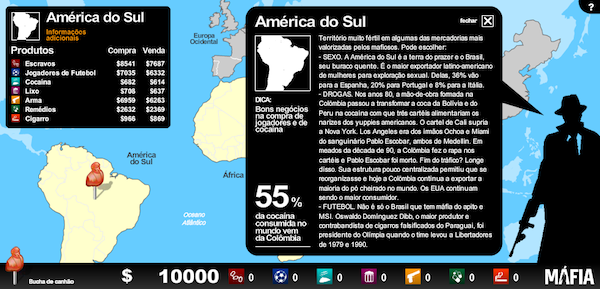

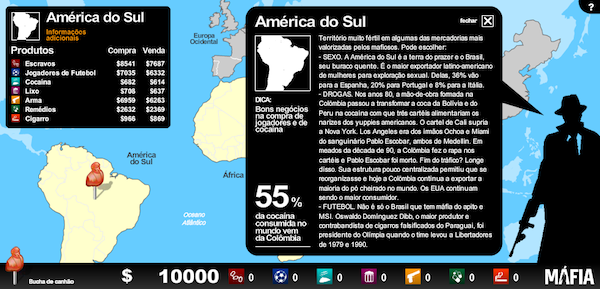

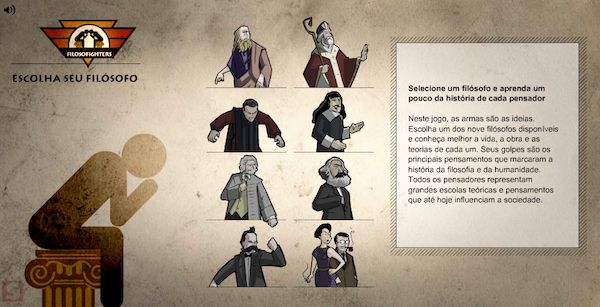

Picture this: In order to understand how the mafia works, you take on the role of an undercover cop posing as a globe-trotting drug trafficker. You answer questions about sex education to continue a strip tease performed by a model. To better understand the teachings of major philosophers, you engage in a battle of theories with them. Though it may sound like a joke, video games are gaining traction as a new way to deliver information on news and current events.

Newsgames are a relatively new format for storytelling, spanning the divide between reporting and video games, and gaining more credibility in the journalism world.

Media outlets like The New York Times, CNN and El Pais have experimented with stories where readers become players in a simulated world. In Brazil, Superinteressante, a magazine from the youth department (Núcleo Jovem) of publisher Editora Abril, is making significant strides in the production of newsgames.

One of those responsible for its success is Fred di Giacomo, who until July of this year was Núcleo Jovem’s editor and is now pursuing an independent career. In this Q&A di Giacomo discusses how newsgames were developed at Editora Abril and offers tips for those seeking to create their own games.

Natalia Mazotte: How did your interest in digital infographics and newsgames begin?

Fred di Giacomo: I worked seven and half years at Abril. After I graduated college, I completed the

Curso Abril de Jornalismo (Abril Course on Journalism) in 2006, and I ended up in the area of digital content. A month later, I was contracted to work for the online section of two magazines,

Bizz and

Mundo Estranho (Strange World). When I began working at Mundo Estranho, I began to work on developing one of the first games launched by Abril,

Strip Quiz. Targeted at adolescents, the user had to respond to questions on sexual education (there were editions on sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy, questions on ejaculation, etc.) and each correct response prompted a model to take off an article of clothing, until she was left with only a bra and underwear. It was one of the site’s main highlights.

Mazotte:Did that promote the development of newsgames for the publishing house?

di Giacomo:The beginning of newsgames at Abril was already planned. The Núcleo Jovem section at Abril (which includes the magazines Superinteressante, Mundo Estranho, Guia do Estudante, and Recreio) had already been a leader in infographics for a long time — the magazines always received awards in Brazil and abroad in that field — so we already had the know-how in visual content. We didn’t know we were doing newsgames, that term wasn’t used. We created infographics, digital magazines, games, and videos. Each brand at Abril had its own policy and different incentives for those things. At Núcleo Jovem there was that incentive; in 2008, the editor for that section was Rafael Kenski, who was a pioneer in Brazil for

Alternate Reality Games (ARG), a type of role-playing game (RPG) based on real life. He was responsible for the first newsgame at Superinteressante, named

“CSI – ciência contra o crime,” which put the player in the role of a forensic cop that demonstrated different investigative methods. It was linked with the cover of the October 2008 edition and was all based on investigative journalism. Kenski thought he was creating a new genre because we still didn’t know about products in other countries.

Mazotte: And when did the term began to be used in Brazil?

di Giacomo: In Brazil, 2007 seemed to be the year that the newsgame format started. That was when, outside of our department, [Brazilian media outlets] G1 and Estadão began to experiment with games. After “CSI,” we made

“Jogo da Máfia,” in 2009, and reporter André Deak wrote a

review about it and used the term newsgames. In other words, during the first games we thought we had invented the wheel, only to discover later that other newsgames had already been made.

Mazotte: How were those first games developed?

di Giacomo: In that time, our team had programmers, designers, and journalists. The programmers used Flash, so we didn’t have a database and gamers’ information couldn’t be saved. That meant the game needed to be relatively simple in order to complete in one session. Players couldn’t return and continue later. On our team we took care of the journalistic part, the testing, and we also thought about the mechanics of the game. Whether it is a question-and-answer game, buy-or-sell game, or some other game. The design was on us.

Mazotte: Is there a difference in the testing process of a newsgame?

di Giacomo: In testing proper there’s no difference. But the way you need to think about the material changes a lot. They are two parallel things, one is traditional testing, which is the same, and the other is the need to think about the mechanics of the game, think about the game design. When you’re building a game, the reporter needs to bring many visual references and should be thinking about images related to the theme in order to recreate the scene. So I would say the big difference is that focus on what will be illustrated.

Mazotte: Outside of the Núcleo Jovem products, a pioneer in the format, how have newsgames advanced in Brazil?

di Giacomo: I have seen some advances from big companies as well as independent ones. At the big companies, the best year was 2011, when Estadão, Globo and RBS also created great newsgames. In 2013, the magazine Contigo! launched a social game called “Cidade de Famosos” (City of Famous People), which had some traits of newsgames

I created a list of Brazilian newsgames. Of the indie games I would cite

“Game Diferenciado” and “Zangief Kid,” which are more like cartoon games that satirize true events.

Mazotte: What’s important in producing a newsgame?

di Giacomo: First you need to think about when it’s worth creating a game. Is the story I want to tell best told through a game, a post, or an infographic? If I wanted to explain how to avoid catching swine flu, for example, I would never do it in a game. Will making a game facilitate understanding of information? That is the starting point. To make a newsgame, you have to ask two questions: Does the game inform? If it doesn’t, it’s only a game. Does the game entertain? If not, it’s only journalism. It’s also necessary to have references. A person who wants to work with a newsgame has to play games, either through a tablet, cell phone or some other platform, or, at least, research them. So one tip is to play a lot and create an ample repertoire. Another thing is to know the theories that already exist. In the United States, Ian Bogost in his book

Newsgames: Journalism at play discusses newsgames and their mechanics. For larger platforms, it is important to have integrated multimedia teams. A journalist needs to understand a bit about programming and design in order to be part of the team.

Mazotte: Who do you follow in the world of newsgames?

di Giacomo: I have more idols in the world of games and infographics than in newsgames, because, even abroad, the format is still very new. One of the most well-known people is

Ian Bogost, who is among the biggest theorists of newsgames. He popularized the term and was one of the first to experiment with the format. Another is

Gonzalo Frasca from Uruguay. In the area of infographics and visual journalism, I would point to

Luiz Iria, a Brazilian and one of the best in the world, also [Spanish visual journalist]

Alberto Cairo, and [Brazilian game developer] Fabiano Onça. Finally, David Cage, of

Quantic Dream, who makes very intelligent games and is taking it to a more mature world.

Mazotte:What has been the response to the games developed by Abril?

di Giacomo: The games vary differently. My experience is that our publication is not necessarily made for avid gamers, but for people who are interested in the topics those games are about and their playability.

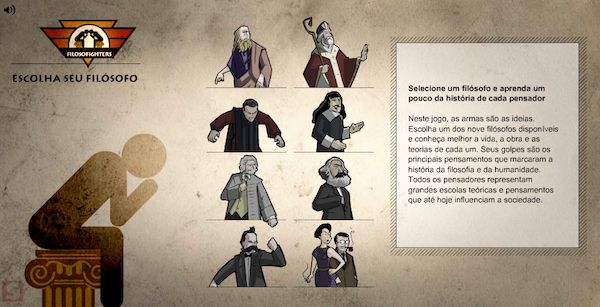

Filosofighters, for example, is a game that brings the teachings of some of the foremost philosophers into a wrestling ring. It had 150,000 visits in the first 45 days. It was a top 10 of the semester. Even today it has to be one of the top 50 most visited sections of Superinteressante. We had another real simple game called “BBB: Paredão da Personalidade” which was the second most visited section of the site year. Later we did a game called

“Corrida eleitoral,” which caused a bit of controversy.

Mazotte: Can newsgames also be a good format for smaller media outlets?

di Giacomo:The difficulty with working with newsgames in independent journalism is the cost. This type of work requires a multimedia team that not every small outlet has. That’s the reason we see a lot of video on independent sites, but still not a lot of games and infographics. But it’s a format with a lot of potential, not only because it can bring more attention — with its enormous simulation power and involvement with the audience — but also to diversify the content and add value to brands. Games are powerful tools, especially for denunciations. There are some interesting examples, such as the game denouncing the civil war in Sudan, and one about narcotrafficking in Mexico.

Mazotte: Have you thought of ways to make this format profitable?

di Giacomo: I think the simple fact of being a new format already gives it value and brings in new audiences. That happened at Superinteressante. Many sponsors began to seek the magazine to promote their own game-like ads on its site. So newsgames will help consolidate a digital image that brings publicity.

We also had an experience with charging for content when we tested social games. At the end of September 2011 Superinteressante launched its first game for Facebook, “Quiz City“, in which the player constructs a city and sees it grow while responding to questions about general knowledge. In that game we created a system of micro-payments in which the user bought credits on Facebook or subscribed to the magazine to win tokens and continue playing. Few people invested while they played. Our intention was not to make an addictive game that tested people’s vanity, like other pay games do, but it was still interesting. We also need to think about whether this is the best way to monetize newsgames. Zynga, one of the best social pay games company, is in crisis, and I would not bet on that path. You end up not prioritizing the information and the best playability of the game. We still need to test. We’re still at the beginning.