Since he arrived at The New York Times in 1999,

Steve Duenes has seen a lot of change.

The Times associate managing editor for graphics finds himself in the midst of multiple revolutions. “Graphics” have moved from their supplemental role in the old world to center-stage on our smartphones and laptops. Smartphones themselves now demand unprecedented thinking in miniaturized storytelling. The newsroom itself has become a different place, with budding collaboration slowly easing out members of competing desks.

In my column this week, I focused on the Times’ creation of what I believe to be the most successful mobile news product. Duenes is one of the many behind-the-scenes leaders of its creation. Our conversation about the changing role of visuals in the business, lightly edited and condensed, is below.

In my column this week, I focused on the Times’ creation of what I believe to be the most successful mobile news product. Duenes is one of the many behind-the-scenes leaders of its creation. Our conversation about the changing role of visuals in the business, lightly edited and condensed, is below.

Ken Doctor: Steve, what led up to the current work?

Steve Duenes: Several years ago, there was a project to create more flexibility in the presentation that we could achieve on the phone and, specifically, in the core app. We called it the “mobile imperative.” More than a decade ago, a majority of our work went from being print to focusing on the web, focusing on desktop, and figuring out what “mobile-first” really meant.

It meant a number of things. It meant more than just a design approach; it meant focusing more resources on news coverage and even breaking news. This is a little bit of a shift within the [graphics] department. It meant doing explanatory journalism, visual explanatory journalism.

We wanted it to be faster, and we want it to be lightweight. Then we needed to develop some ways of working that would be elegant on the desktop, with a responsive design that could be built quickly for the phone….We started to make that shift by building out lots of graphic stories.

The Upshot creates a lot of these, with a combination of images, words, and graphics.

Doctor: The Upshot is interesting because it kind of was born into that mobile revolution and seems as if it was one of the first sections in which explanatory graphics were thought of from the beginning of each piece.

Duenes: Yes, as a formal section. Before The Upshot came together as a formal department, it was apparent what was going on with it. Two of the heavy editors from the graphics department,

Amanda Cox and

Kevin Quealy, were a big part of sort of establishing that rhythm. That led in the direction of more explanatory work, faster response, trying to be sort of modular and lightweight in a kind of a template. There’s [now] a pattern of explanatory visuals making their way into the story itself. They are complementary, but don’t really overlap with content that’s in the story. They are standalone pieces that come alongside written articles.

Doctor: You’ve seen quite an evolution in what “graphics people” do in newsrooms.

Duenes: Fifteen or twenty years ago, Graphics was more of a service desk. It’s not a service desk anymore. The graphics department is really a news desk and works in parallel with the other news desks like Metro and National and International.

There is coordination, and there’s a positive effect from that coordination, but especially with news coverage and breaking news, it is independent work. The graphics department figures out lines of reporting, does the reporting, starts to build visuals. There are small teams that form organically and quickly around how we’re going to respond to these stories.

Doctor: Was there an exact time when that switch was thrown and you became more independent?

Duenes: It was gradual. It took time because the culture of the newsroom had to accept it. There are a lot of desks that kind of feel like this is a part of their report and they should order these things up to be part of their report. If it’s an independent desk, and it becomes a different conversation, it takes a little while, culturally, to get to that different conversation.

The graphics desk can publish something on its own and then, the next day, point it out to the national editor and have the value of that piece be apparent. That’s the kind of thing you need to make that cultural change, and that’s what happened in this department. The graphics department decided — before the newsroom really got into the swing of switching into a digital-first operation — that that’s how they were going to work.

It’s just grown from there: The desk has grown, the reporting resources in the department have become stronger and the additions have been people with deeper, specialized skills, developers, cartographers who are also coders.

Doctor: Give me a sense of the size of the department. How much do you have in terms of, say, reporters or reporting resources?

Duenes: There are a quite a lot of people in the department who are capable of pretty good research, people who do decent reporting, and then there are, I’d say, six or seven members in the department who are very strong reporters and are really great at finding information that’s hard to get. The desk itself is a little bit above 35 people.

Doctor: Thirty-five in total, including reporters, designers, photographers, and editors?

Duenes: That’s right.

Doctor: What was that number about two years ago, do you think?

Duenes: It’s probably grown by a few. I think it was at least 10 fewer when I got here and it has gone up and down. Now we actually have to make a couple of hires and I think it will be about 38 or 39.

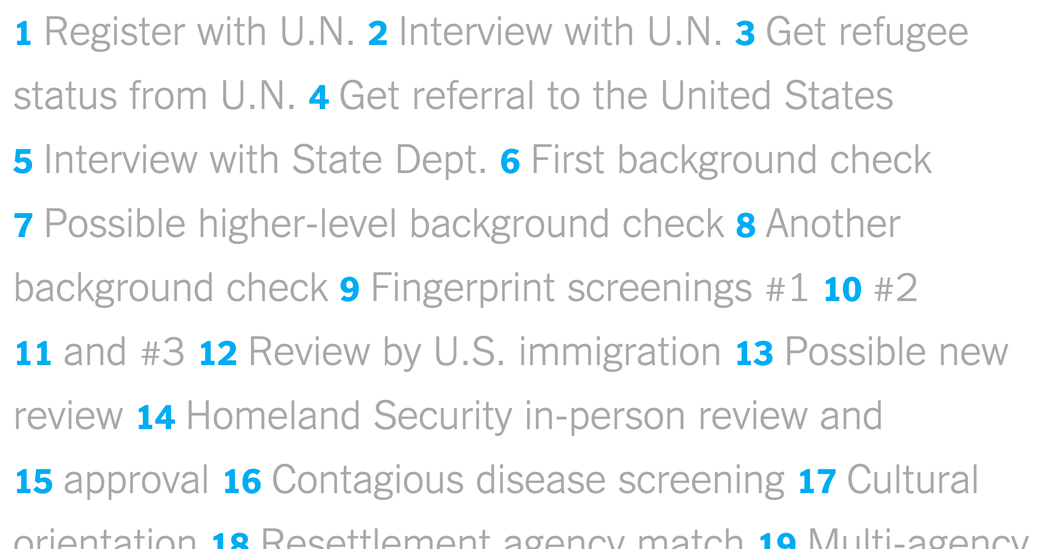

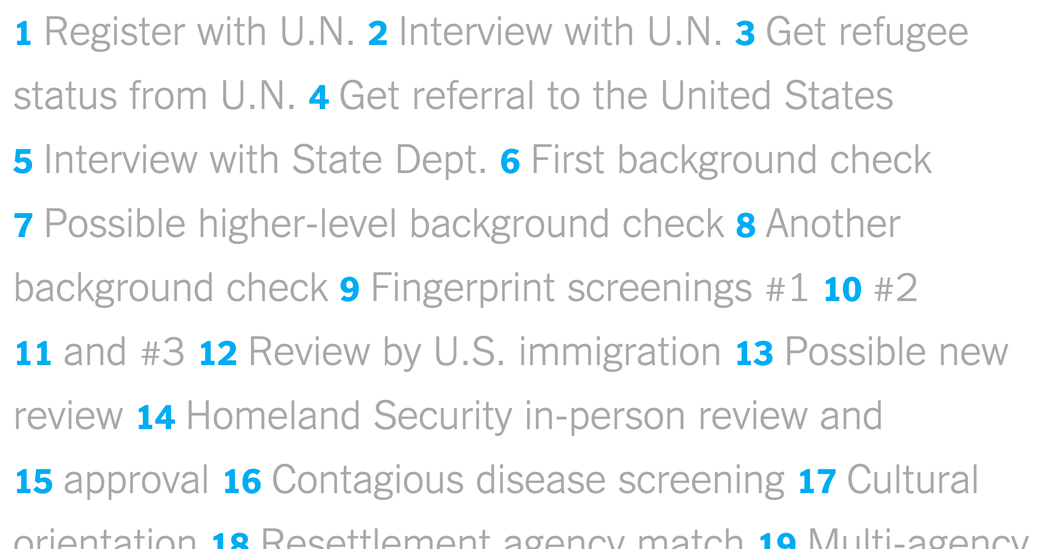

Doctor: For these pieces on the Times’ mobile presentation, I’ve been clipping graphics on my phone. One that stood out is about the twenty steps Syrian refugees have to go through to get into the U.S. You put that at the top of the story, giving it great play on the home page.

Duenes: Yeah, that was a nice piece…I do think it’s, like, getting to a place where you’re sort of on equal terms with a written article. That’s what we want, and I think that’s where we’re going.

Some of the graphics, if we are turning them around quickly, can be as simple as, for example, two visualizations, an extended caption, and applying it together to make a larger point. Some of them are more elaborate versions of those.

Large numbers of people are viewing them. The traffic on the explanatory stuff has been strong, but the question that we were asking ourselves was, “Are we getting a little formulaic?”

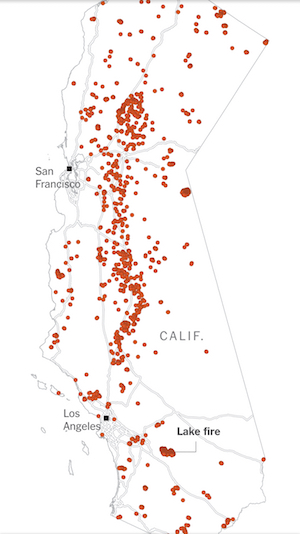

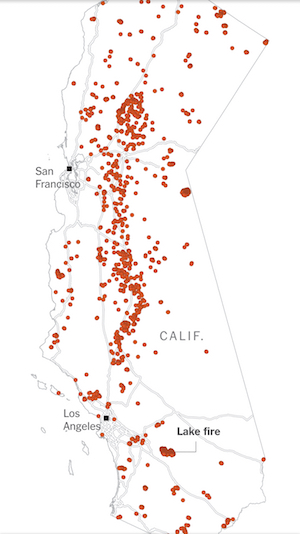

We’re asking, “Do you want to try to take stories that are built around explanatory visuals and push in a narrative direction?” One piece like that was a curtain-raiser on wildfire season in California. One graphics editor had done a lot of reporting and figured out very early in the season that there had already been many more fires than in previous years, and because of the drought, it’s just going to be a disaster.

We’re asking, “Do you want to try to take stories that are built around explanatory visuals and push in a narrative direction?” One piece like that was a curtain-raiser on wildfire season in California. One graphics editor had done a lot of reporting and figured out very early in the season that there had already been many more fires than in previous years, and because of the drought, it’s just going to be a disaster.

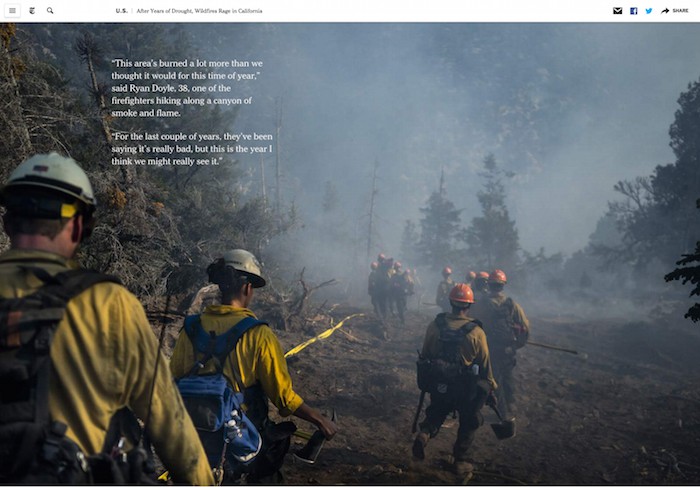

As visualizations, they were a little abstract. They were not necessarily put-you-there kinds of visuals. We started to talk to the national desk and it was a great start to go to a fire, do some on-the-ground reporting, and set this story as: Here’s a fire that’s happening now, here’s the next one that’s coming up.

Doctor: I live in the Bay Area, and I remember it.

Duenes: If you scroll down that story, it started with that map of the entire location from January to July. We started with that, the fly-over aerial survey of all the dead trees, and some of the charts. We were thinking of stringing it together as a graphical kind of explanatory piece: Wildfire season is going to be bad.

The rest of the piece grew out of that. Now, the intro to the story addresses the scene you’re looking at in the photo that sits behind it. With the next photo, you have more copy about firefighters hacking along the canyon of smoking flames, and you’re seeing it.

Ultimately, we’re talking about this relationship between [different types of] visual information. It could be visualization, it could be photography, it could be video, it could be the word. There’s a power to that relationship.

Doctor: As you have developed your new routines, do you have categories of graphics that you talk about? In the old, print days, we would talk about a cartoon, an infographic, two or three other things. Do you have a toolbox where you identify, here are the six major forms we use?

Duenes: Not exactly…There’s a vocabulary across just pure visualization types. We’ve been talking about in the story forms, and one story form was the stack. That’s not an elegant name, but it’s shorthand for the fast response to a breaking story in a form that’s going to read elegantly both on the desktop and on the phone, and that will display visuals that answer readers’ basic questions about a breaking news story.

Photo of Steve Duenes by Earl Wilson for The New York Times, used with permission.

In my column this week, I focused on the Times’ creation of what I believe to be the most successful mobile news product. Duenes is one of the many behind-the-scenes leaders of its creation. Our conversation about the changing role of visuals in the business, lightly edited and condensed, is below.

In my column this week, I focused on the Times’ creation of what I believe to be the most successful mobile news product. Duenes is one of the many behind-the-scenes leaders of its creation. Our conversation about the changing role of visuals in the business, lightly edited and condensed, is below.

We’re asking, “Do you want to try to take stories that are built around explanatory visuals and push in a narrative direction?” One piece like that was a curtain-raiser on wildfire season in California. One graphics editor had done a lot of reporting and figured out very early in the season that there had already been many more fires than in previous years, and because of the drought, it’s just going to be a disaster.

We’re asking, “Do you want to try to take stories that are built around explanatory visuals and push in a narrative direction?” One piece like that was a curtain-raiser on wildfire season in California. One graphics editor had done a lot of reporting and figured out very early in the season that there had already been many more fires than in previous years, and because of the drought, it’s just going to be a disaster.