A declining newspaper is better than no newspaper. A rundown newspaper is better than no newspaper. A bad newspaper is better than no newspaper.

Some people will disagree with me there. There are those in the local digital news world who argue that it’ll take the final shutdown of a city’s daily to trigger the changes that can make vibrant local online news workable — and, by extension, that any help given to those declining dailies is just postponing that glorious transition. Maybe. But my strong suspicion is that, whenever a local newspaper closes, whatever evolves next is unlikely to replace whatever journalistic firepower has been lost.

Apparently, we’ll soon get a chance to find out.

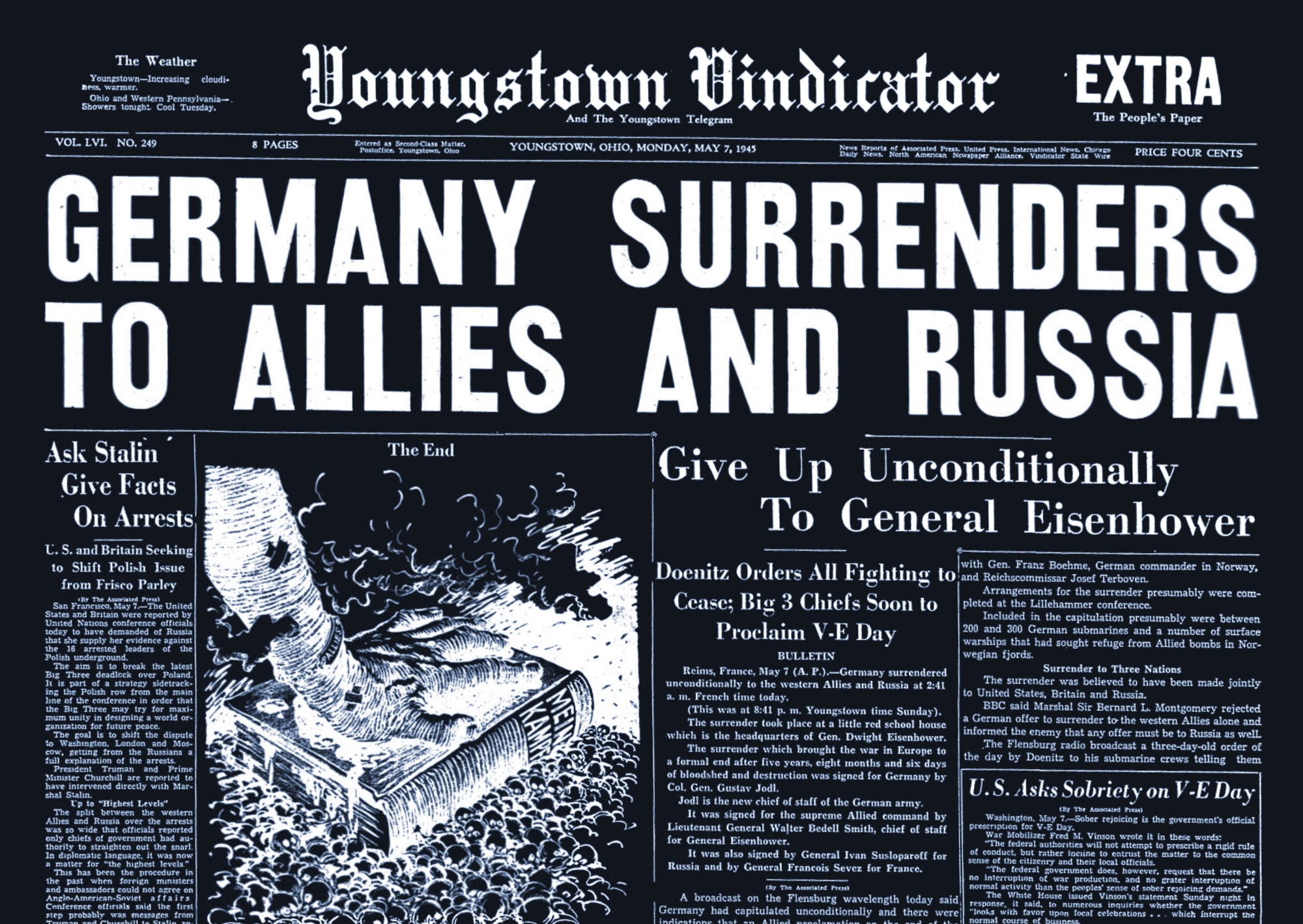

For the past decade, daily newspapers have been shrinking, not shutting down; since 2004, only about 60 U.S. daily newspapers have closed out of more than 1,300. Most of those were two-paper cities becoming one-paper cities or two or more neighboring dailies merging into one. But now we’ll have a decent-sized American city with no daily newspaper at all. On Friday, The Vindicator of Youngstown, Ohio announced it would be shutting down for good at the end of August. Youngstown is a city of 65,000 anchoring a metro area of 540,000. The Vindy, as it’s known, was only a few days past celebrating its 150th birthday.

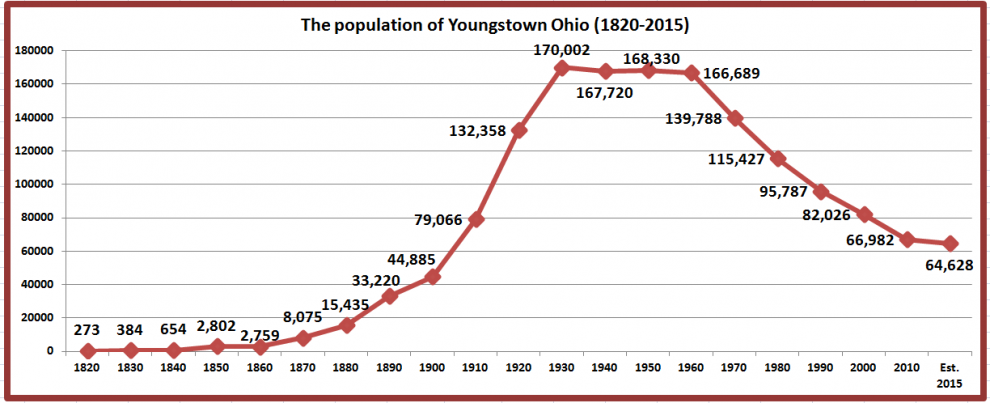

It’d be relatively easy to think of this as a Youngstown story. If you had to come up with the single American city that best evokes the phrase “Rust Belt decline,” Youngstown would probably be your choice. Its flagship employer, GM’s Lordstown Assembly, stopped production in March and is being sold to a company that may or may not be able to do anything with it. And Youngstown’s decline goes back much farther; population charts over time aren’t supposed to look like flat-top mesas.

But I don’t think this is a Youngstown story. I fear we’ll look back on this someday as the beginning of an important (and negative) shift in local news in America.

Because there are, broadly speaking, two groups that are going to determine the near-term futures of local newspapers: on one hand, family and small-scale chain owners, and on the other, the big national chains seeking to maximize scale and efficiencies on the cheap. And neither of those groups could see a way to keep a daily newspaper alive in Youngstown.

First consider the Vindy’s current owners, the Maag-Brown family. William F. Maag, Sr. bought The Vindicator in 1887. Control of the paper passed to his son, then his son’s nephew, then the nephew’s widow, then their son — four generations of family ownership. The family matriarch, publisher Betty J.H. Brown Jagnow, has worked at The Vindy in some capacity for the past 71 years. If you want to lionize family ownership of newspapers, this is your kind of family.

The family, like a lot of its peers in the mid-20th century, was smart enough to expand into broadcasting; they own the NBC and CW affiliates in town. And those TV profits made it easier to swallow losing money in print; general manager Mark Brown (Betty’s boy) said the Vindy has lost money in 20 of the last 22 years. The Vindy’s website shows a still relatively well-stocked newsroom, the sort that a chain owner might have stripped to beams years ago. I count 24 journalists, assigned to the meat-and-potatoes beats that need covering in a community: city hall, education, police, social services, health, politics. Back in the 1990s, a newspaper rule of thumb held that you could afford one journalist for every 1,000 in daily circulation it had; given that the Vindy’s daily circulation today is 25,000, that means its owners hadn’t cut to the bone.

When we talk about newspaper ownership in America, the focus is usually on the biggest players — Gannett, Tribune, McClatchy, and so on. And in larger metro areas, those chains do own a healthy share of the nation’s dailies. But they are each still a small fraction of the total newspaper market. (Gannett, Tribune, and McClatchy combined would still only own about 1 in 9 U.S. daily newspapers.) There are still a ton of newspapers that are either still owned by families or by smaller regional chains that, while perhaps not local, generally aren’t pillaging newsrooms to meet a Wall Street earnings target.

A lot of those families are tired. They’ve been fighting the demise of print advertising for more than a decade now, they see the direction things are headed, and they don’t like the idea of treating breakeven as a stretch goal. They’re pretty sure convincing their sons or daughters to move back from Brooklyn someday to take over isn’t going to happen. They want to get out.

Families have been wanting to get out of the newspaper business for generations, and their path out has usually involved some version of that second group — newspaper chains. Gannett and others built themselves up for decades by having the capital to offer liquidity, the capacity to run distant newsrooms at scale, and a business model that investors found appealing. If you owned the monopoly daily newspaper in your community and wanted to sell, you’d hire a broker and find no shortage of offers. There was always someone willing to buy. Always.

But…not in Youngstown. The Vindicator hired a newspaper broker in December 2017 and got substantial interest from only two chains. Each eventually backed out, and “so we ended up with no potential buyers,” Brown said.

He wouldn’t name the chains, but one was almost certainly GateHouse, which owns six other daily newspapers within a 90-minute drive of Youngstown. GateHouse exists in its current form for one reason: to buy up newspapers. It’s spent more than $1 billion doing so in the past five years; it’s the sort of company that gets called “omnivorous” in headlines. And yet it apparently wasn’t interested in adding The Vindicator to its stable.

Is that because Youngstown is a uniquely bad market? Maybe. But in per-capita income, the Youngstown metro area ranks 180th out of 280, not down at the very bottom. Its unemployment rate is 6.2 percent — not great, but also not apocalyptic. No one is saying Youngstown is some great blue-ocean media market, but it’s also not all that far from where a lot of cities are economically away from the coasts.

It’s the combination here that’s a very bad sign: a small-scale owner that wants out and a large chain that says “nah, we’re good.” The energy in the newspaper business for the past half-decade-plus has all been toward consolidation: roll all these individual papers and small chains into one giant GannettHouseDFMTribClatchyCorp and let corporate efficiency buy everybody a little more time. But in at least in this one case, the consolidators have decided that financially there’s nothing of value left to consolidate. The tricks they’ve been using — cut staff, outsource editing, outsource production, regionalize ad sales — apparently weren’t worth trying in Youngstown. And that’s scary as hell.

What’s going to happen to Youngstown? It still has TV stations. There’s a public radio station. There’s a news radio station (current headline: “Body Partially Eaten by Alligator Being Investigated by Florida Police”). Maybe a paper a town or two over will decide to start a Youngstown edition with a few stories every week. There’s a young man who has proclaimed, apparently not up on trademark law, that he would be starting an online site called the “Valley Vindicator”; he calls himself “The Godfather of Advertising,” so who am I to doubt him?

But is anything actually going to fill that Vindicator-sized hole? I’d love for someone to prove me wrong.