Remember Rafalca? Ann Romney’s horse? The one who was competing in the Summer Olympics while Ann’s husband Mitt was running for president against Barack Obama?

Rafalca wasn’t a huge hit at the judges’ table — she finished 28th; I mean, you try and out-point a stone-cold legend like Valegro — but she did introduce a new audience to the world of dressage, a word so evocative of third-tier continental royals that it seems to demand italics.

In Rafalca terms, dressage asks horses to perform a set of predetermined moves, most derived from Jason Sudeikis’ dances on “What’s Up With That,” maximized for precision and only a hint of guidance from whoever is sitting on top of them.

In media terms, though, dressage means something different — something closer to the word’s meaning in French, “training.” It comes from the French Marxist intellectual Henri Lefebvre and his posthumously published book Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. (Content warning: French Marxist intellectual content.)

To enter into a society, group or nationality is to accept values (that are taught), to learn a trade by following the right channels, but also to bend oneself (to be bent) to its ways. Which means to say: dressage. Humans break themselves in [se dressent] like animals. They learn to hold themselves. Dressage can go a long way: as far as breathing, movements, sex. It bases itself on repetition.One breaks-in another human living being by making them repeat a certain act, a certain gesture or movement. Horses, dogs are broken-in through repetition, though it is necessary to give them rewards. One presents them with the same situation, prepares them to encounter the same state of things and people. Repetition, perhaps mechanical in (simply behavioural) animals, is ritualised in humans. Thus, in us, presenting ourselves or presenting another entails operations that are not only stereotyped but also consecrated: rites…

Breeders are able to bring about unity by combining the linear and the cyclical. By alternating innovations and repetitions. A linear series of imperatives and gestures repeats itself cyclically. These are the phases of dressage. The linear series have a beginning (often marked by a signal) and an end: the resumptions of the cycle [reprises cycliques] depend less on a sign or a signal than on a general organisation of time. Therefore of society, of culture.

Here it is still necessary to recognise that the military model has been imitated in our so-called western (or rather imperialistic) societies. Even in the so-called modern era and maybe since the medieval age, since the end of the city-state. Societies marked by the military model preserve and extend this rhythm through all phases of our temporality: repetition pushed to the point of automatism and the memorisation of gestures differences, some foreseen and expected, others unexpected the element of the unforeseen! Wouldn’t this be the secret of the magic of the periodisations at the heart of the everyday?

To be slightly less French about it, think of dressage as the socially influenced repetition of a behavior to the point that it becomes both habit and ritual.

Before the internet, the consumption of news was profoundly driven by habit and ritual. A typical person might read the same newspaper at the same time every day; listen to the same radio station while driving the same route to work every day; watch the same news broadcast at the same time every night; and hear jokes based on headlines from the same late-night host every night. Some of those habits were driven by personal choice. (Did your house watch Peter, Dan, or Tom?) But others were created by outside structures. (What time was the newspaper delivered? What anchor was on air during your morning commute? Would you like your TV news at 5, 6, or 11 p.m., or not at all?)

The internet (and, especially, smartphones) exploded most of these habits and rituals. News suddenly existed everywhere and at all times, packaged into all formats, backed by all ideologies, and aimed at all audiences worth showing a banner ad. This was exhilarating, but it also opened doors to all sorts of bad actors. And when habits disappear, new ones grow to replace them. What shape do our new digital news habits take?

That’s the question behind a paper in the new issue of Digital Journalism, by Henrik Örnebring and Erika Hellekant Rowe. The abstract:

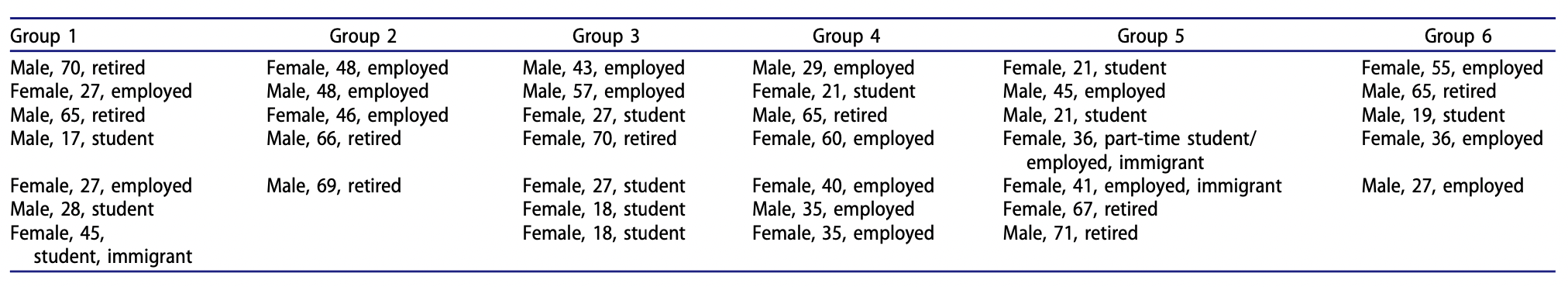

Studies of hyperlocal journalism and news have not adequately taken into account audience members’ everyday experiences of their own hyperlocal communities and the ways in which audiences’ everyday information environments are integrated with their social and affective community environments.In this focus group study (six groups, 5–7 participants/group, total N = 38) of neighbourhoods in Rivertown, Sweden (a mid-sized Swedish municipality) we combine Henri Lefebvre’s theory of rhythmanalysis and his idea of “the media day” with Ray Oldenburg’s concept of third places to analyse the spatiotemporal aspects of hyperlocal information environments.

The focus group participants created individual “media day” timelines and then discussed them, and their neighbourhoods, in the groups. Our findings are in line with other recent studies on digital and local news and information consumption, but also highlight how the media context has changed since Lefebvre’s and Oldenburg’s studies.

In particular, we found that their juxtapositions of “authentic” interpersonal communication and “inauthentic” mediated communication still have some relevance in the contemporary media landscapes (particularly as related to the existence of neighbourhood third places) and that some hyperlocal digital information sources (Facebook groups) appear to contribute to dressage in Lefebvre’s sense.

(My usual Scandinavian disclaimer: This study was done in Sweden, an imaginary faraway land filled with sugar-plum fairies, mighty Vikings, and — through a combination of language isolation, state policy, and general civicmindedness — a media ecosystem that is unusually healthy in many ways. Elsewhere, YMMV.)

I am very much on board with the core argument here: Both journalists and academics have spent more time thinking about the supply of local news than the demand for it. That’s understandable! The supply side has been under fiscal threat for the past two decades, and if there’s no supply, demand doesn’t much matter. And in the old days of habit-driven news consumption, how many people an individual story actually reaches was both unknowable (Did anyone read that brief at the bottom of page A31?) and not all that important to the business model. But in digital, you can’t count on a monopoly distribution channel to make sure important news is reaching an audience at scale. Which is why the general turn to the audience the past decade or so has been both welcome and insufficient.

There is widespread concern about the information needs of audiences and the lack of mediated information about community concerns…However, this kind of “information ecology/news ecosystems” research on local news audiences has provided limited insights into how audiences make and construct meaning in everyday social contexts, as well as into aspects of community engagement and belonging not strictly linked to information provision…By contrast, these latter issues are addressed in some recent qualitative research on people’s online news and information habits that highlights the complexities, contradictions, and situatedness of news media use, hyperlocal or otherwise. Memorable summaries from some of these studies for example note “…news users do not always use what they prefer, nor always prefer what they use”; that “…time spent does not necessarily measure interest in, attention to or engagement with news”; and that (from a study of temporal aspects of everyday news/information consumption) “in neither of the examples presented here do we see an audience which is disoriented, distracted, overloaded or uninterested.” News audiences defy expectations: their stated preferences may not match their actual behaviours; they may not even perceive categories news producers and scholars see as self-evident; and they may care about particular types of contents or communication channels for reasons entirely unintended by producers.

The authors here use Lefebvre’s concept of “the media day“; from Rhythmanalysis:

Producers of the commodity information know empirically how to utilise rhythms. They have cut up time; they have broken it up into hourly slices. The output (rhythm) changes according to intention and the hour. Lively, light-hearted, in order to inform you and entertain you when you are preparing yourself for work: the morning. Soft and tender for the return from work, times of relaxation, the evening and Sunday. Without affectation, but with a certain force during off-peak times, for those who do not work or those who no longer work. Thus the media day unfolds, polyrhythmically.

That polyrhythmia — different layers of your environment (media and otherwise) pushing at different speeds, all at once — is one of the key ideas being used here. Another is Lefebvre’s aforementioned dressage: “techniques and strategies to ensure that bodies accord with and conform to dominant rhythms.” The third is Ray Oldenburg’s idea of “third places” — cafes, bookstores, libraries, bars, and other spaces that serve as places to hangout that are neither your home nor your workplace. These third places can strengthen feelings of community, and they can shape how a community thinks about itself.

Örnebring and Hellekant Rowe do their research in the anonymized city of “Rivertown,” a place with 94,000 residents and what, by U.S. standards, is a pretty healthy media ecosystem:

There are two daily newspapers (currently they have the same owner but were in competition until their merger a few years ago), one weekly newspaper, several local freesheets of variable periodicity, a local public service television station, a local public service radio station, and a local community radio station.

For comparison, some American cities with about 94,000 residents: College Station, Texas; Fall River, Massachusetts; Livonia, Michigan; Portsmouth, Virginia; Yuma, Arizona. Not a lot of two-newspaper towns left at that weight class.

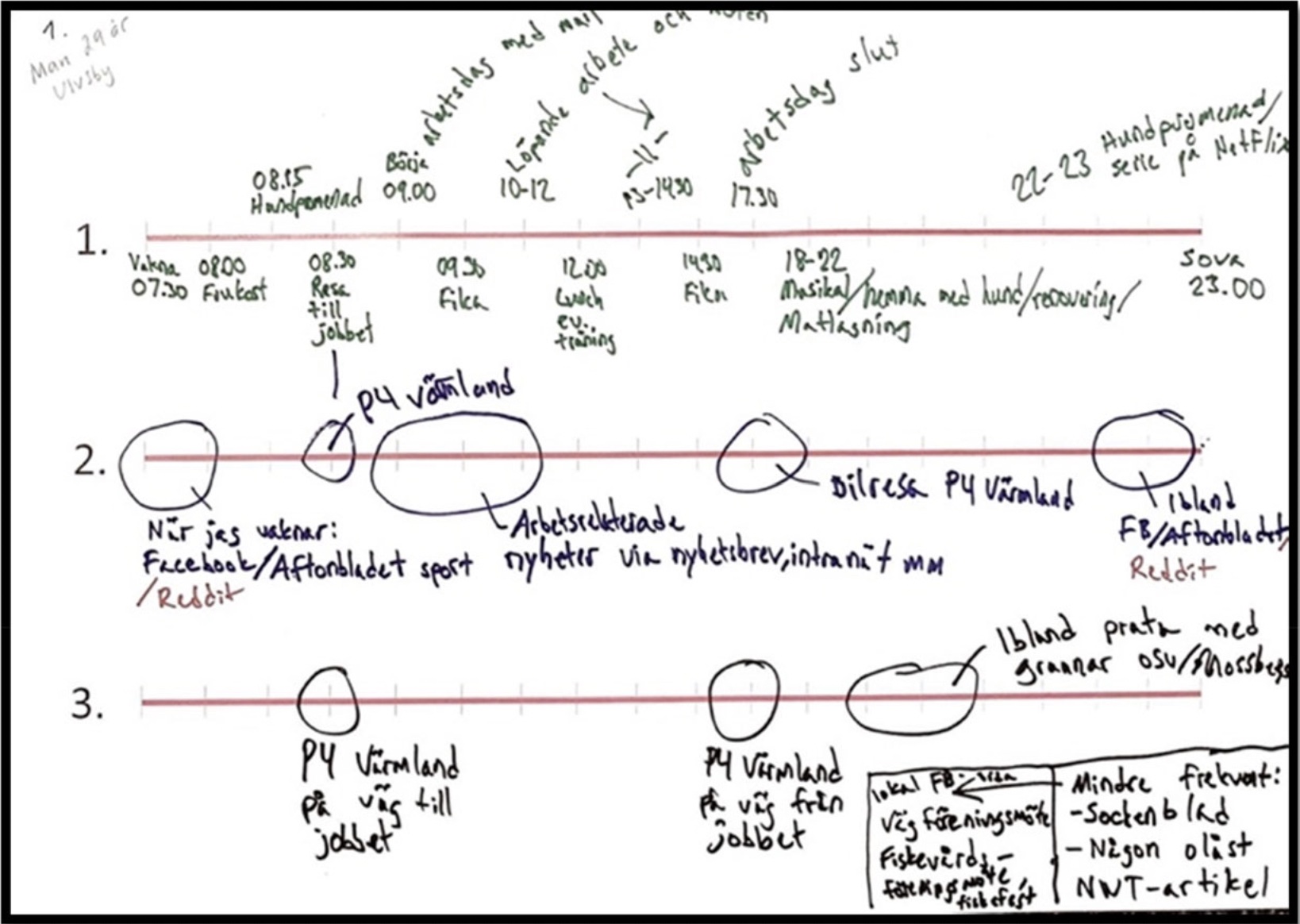

They held six focus groups, with people drawn from six different neighborhoods (selected to generate “a mix of urban/rural, city centre/suburban, and high/mid/low income”). Each participant was asked to chart out the key events of their “typical ordinary day,” followed by “when and what type of news and information” they consumed along the same timeline. Then the same question just for local news and information, followed by whatever else they felt like adding. Their timelines ended up looking something like this:

Örnebring and Hellekant Rowe then assembled all the focus group timelines and looked for commonalities and patterns. This is what they got (click to enlarge):

The different times marked by participants on their individual timelines where all noted on this common media day timeline, ranging from morning through midday and into the afternoon and evening. We counted the number of mentions by individual participants using a particular type of medium at a particular time, and noted this down on the media day timeline (these are the numbers within the geometric shapes)…This is not intended as a systematic quantification, merely as an illustration of what patterns were more and less common in this specific, small group of people (other groups may well have different habits and rhythms). The different news outlets were grouped by type and differentiated in the diagram using different-coloured geometric shapes…

Some participants mentioned using their mobile phones to continuously check social media platforms and digital news publishers throughout the day (i.e., not linked to particular times), and some mentioned getting news notifications from their mobile phones throughout the day. We represented this by creating two “lines” of star shapes that stretch along the whole of the media day. The sizes of all these geometric shapes are proportional to the number of participants who mentioned using that media/news type at that particular time.

I don’t think there’s anything shocking here, at least for the Swedish, who are much more into print newspapers than Americans are. The most shared rhythms involve starting the day with news sites on your phone in bed; reading a print newspaper at the breakfast table; listening to the radio in your car; a digital check-in for news around lunch and after work; then sitting down in front of the TV at night. Social media and news alerts slip into any available crevice throughout waking hours. Broadly speaking, pre-internet media still seem anchored to time and habit, while digital spills everywhere like water — though visiting digital news sites seems more schedule-bound than other online activity.

But the subjects reported the ritual-tied and ritual-less behaviors felt different, somehow:

It was clear from the focus groups accounts that there still is some relevance to Lefebvre’s distinctions between an authentic presence and an inauthentic, media-driven present, at least in terms of people’s affective reactions. Broadcast scheduling — so central to Lefebvre’s analysis of the media day — still retains its important role in people’s everyday lives and help anchor other rhythms (e.g., people planning meals to fit around watching desired TV programs)…Yet these legacy media were viewed as the authentic or alternative to the extended and individualized “now” of digital and social media feeds. Discussing the newspaper with family members in the morning or discussing the TV broadcast with family members in the evening was viewed as a nice way to get away from the rhythms of constant social media checking. In the contemporary context, the scheduled rhythms of legacy media were naturalized enough to feel like a relaxing presence (i.e., often linked to synchronous dialogue with other people), as opposed to what we could call a rhythm of the feed linked to social and mobile media that could sometimes be perceived as a stressful present.

Rather than being linked to specific times, regular intervals, and often particular places, the rhythm of the feed was continuous, often ambient, characterized by irregular spikes of attention, and (because it often comes via the mobile phone) particularly linked to places associated with waiting and/or inactivity (e.g., bus stop, on the bus on the way to work). Yet the rhythm of the feed still had regularities: concentrated in breaks and interstitial times during the day, used to fill the gaps in other rhythms. The rhythm of the feed was associated with social media but not limited to a single platform…

Lefebvre’s distinction between the perpetual “now” of the present provided by the media and the authentic presence provided by other people in everyday life thus applies to the rhythm of the feed — more so than the rhythms of scheduled legacy media, which today sometimes seem quaint, old-fashioned, and “real” compared to social media feeds and mobile flows.

And the sources of local news and information participants considered important weren’t limited to the products of media companies.

In some of the areas, particular individuals or groups of individuals were mentioned as particularly important sources of hyperlocal news/information via direct, face-to-face dialogue: the woman at the cash register in the local grocery store (in Wolf Village); a woman at the local high school (in Bonfire Hill). These people all worked at third places in the community…and as such it was easy for a variety of people to come across them as part of other rhythms (e.g., household rhythms of consumption, in the case of the grocery store, or the rhythms of the school day and the school year, in the case of the school). Everyday rhythms intersect in interpersonal meetings and create information exchanges that are characterized by dialogue rather than communication.

In all, participants found it harder to identify the daily rhythms of their local news consumption than for national and international news. Some of the irregular sources of local news they identified:

Notice how many of those are associated with “third places” — a church, a library, a school. You’re probably not going to get the latest from Ukraine on a corkboard in an apartment building lobby, but it might be precisely the place to learn about a local political issue or an interesting speaker coming to town.

Örnebring and Hellekant Rowe describe local Facebook groups as a sort of virtual third place, sharing a common space but without the physical presence of a common place. Of particular note were local “crime-watch” Facebook groups:

Crime watch Facebook groups were an essential part of the daily media rhythm for some participants; one participant had subscribed to continuous notifications from the local crime watch group, with a particular interest in the part of the neighbourhood closest to him (i.e., wanting to be notified if there were any crimes reported in his particular street).We can thus make no general conclusions about virtual spaces (in our case mainly Facebook groups) as third places. Some groups, such as the ones clearly linked to local community organizations in Wolf Village, either have some third place characteristics or function as extensions of other local third places. Crime watch groups, by contrast, functioned more like what we would call hyperlocal dressage: community members learning about what is “Other” and what is acceptable and what is not acceptable as they moved around in their neighbourhood. These Facebook groups were used to keep track of the neighbourhood — particularly the areas closest to one’s home — and watch for suspected criminal activity or other inappropriate actions — not as third places.

In all, the authors find that there’s still some air in Lefebvre’s critical tires, despite the fact he was writing for an ink-and-broadcast-towers world. Back then, he argued that the artificial rhythms of media — the morning newspaper, the 6 o’clock newscast, the top-of-the-hour bulletin — were inauthentic when compared to the authentic presence of face-to-face contact. But now:

The scheduled media rhythms deemed inauthentic by Lefebvre now seem more authentic that the continuous present created by news notifications, feeds and mobile digital flows. Dialogue is extended through time and space via new media and not in opposition to mediated communication — yet the continued (if weakened) existence of third places point to the still-important role of face-to-face-communication in hyperlocal information environments…News organizations historically contributed independently to rhythmic dressage through teaching people to read the newspaper every morning or watch the news broadcast every evening, but today their attempts to keep audiences hooked through apps, newsletters, notification schemes and other things are an adaptation to an infrastructure not under their direct control. This infrastructure…is designed to intrude into our everyday life — particularly those aspects of everyday life related to information consumption.

As news organizations attempt to assert their continued relevance and legitimacy under these new infrastructural conditions and using the new digital tools at their disposal, they must also reflect on whether their complicity in and indirect support of this “like economy” is consistent with often-invoked values of democracy and participation.