The soundbite that will circulate in the journoblogosphere for the next 24 hours, from columnist and Newser founder Michael Wolff on a panel discussion with Craig Newmark and Bennett Zier:

The soundbite that will circulate in the journoblogosphere for the next 24 hours, from columnist and Newser founder Michael Wolff on a panel discussion with Craig Newmark and Bennett Zier:

About 18 months from now, 80 percent of newspapers will be gone. The Washington Post is supported by Kaplan’s testing business. The testing business will still be around in 18 months, and they will probably continue to support the newspaper. But that’ll be an exception.

Now, I have a bunch of predictions hanging out there myself — some have come true already, some have already turned out to be off the mark, the rest are wait-and-see — but this one is a real doozy. There are still about 1,430 daily papers in the U.S., so what Wolff’s prediction means that we can expect the extinction of 1,144 of them. Which works out to, let’s see, a little over two per day, every day, for 18 months. Sorry, that’s not happening.

To be sure, the industry is in deep, deep trouble. Most of the top 10 or 15 newspaper owners are bankrupt or close to it, and are in or near penny-stock territory. They don’t have two cents worth of credit left, and couldn’t raise the money for the most lucrative acquisition imaginable. Which (aside to Matt Ingram) is why there’s not much creativity coming from them. (Amazingly, most newspaper firms are slogging on under the leadership of the same CEOs, which is part of the problem.)

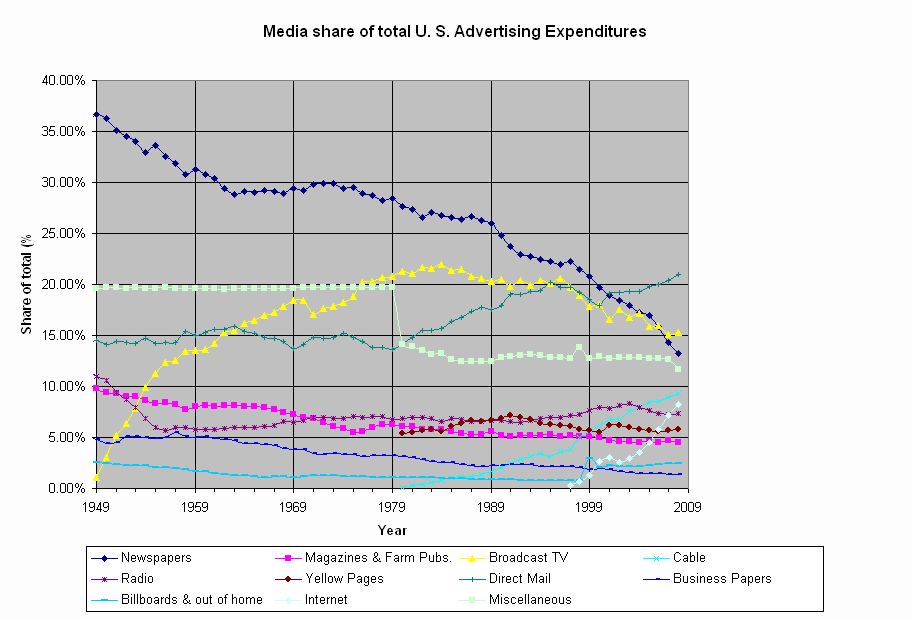

And, to be sure, ad revenue has been heading downward not just for a few years, but in truth, when measured in relation to all other media, for more than 60 years (that dark blue line):

(Data from Universal-McCann via the Television Bureau of Advertising; also from Internet Advertising Bureau, National Cable and Telecommunications Association.)

(Data from Universal-McCann via the Television Bureau of Advertising; also from Internet Advertising Bureau, National Cable and Telecommunications Association.)

Yes, 60 years ago, newspapers took in 37 percent of all ad dollars in the U.S., and it’s been steadily downhill ever since. (A century ago, it was probably 75 percent or more, but nobody was measuring.) In 2008, preliminarily (some figures are still estimated), they’re looking at 13 percent, down from 18 percent five years ago. In a year or two, internet advertising (that’s the upwardly mobile line of light blue diamonds) will have a bigger slice than newspapers. We know the reasons: loss of national advertising to TV, loss of monopolistic ad pricing power, loss of classifieds to Craigslist, etc.

Moreover, circulation is dropping like a stone (down 4.8 percent for the six months ending last September 30, and we’ll get a similar stat for the October-March period any day now). As the print audience is lost, it disperses online and is not retained on newspaper web sites.

This doesn’t look like a formula for survival, so why is Michael Wolff wrong in predicting an 80 percent shutdown rate? Because 73 percent of America’s newspapers have a circulation of 25,000 or less. Another 13 percent were in the 25,000-50,000 bracket. So 86 percent of the daily newspapers in America are in small towns and cities. And yes, some of them lose money, because things are not good in those towns right now. But the vast majority of those papers are profitable. Not as profitable as they once were, but they were profitable during the Depression (I’ve seen some of the old P&Ls), they’re profitable now, and they’ll be profitable 18 months from now.

The problem is that newspaper owners have leveraged their cash flow to the hilt to make risky, ill-considered acquisitions that have now put many of them at, or over, the brink of bankruptcy. Their larger assets — most of the top 100 or so papers (those over 90,000 or so in circulation) — are probably in the red on an operating revenue basis, because they lack the grass-roots small-business advertising support the small dailies have, and are saddled with expensive real estate, distribution arrangements and union contracts. Hence threats to close papers like the Boston Globe and San Francisco Chronicle. But even if all the chains go bankrupt, operationally profitable assets like small-town dailies will be sold off intact, not shut down.

Even those metro-sized papers will, for the most part, survive the next 18 months, although most of them will cut further their distribution, their contents, and if they’re smart, their publishing frequency down to 1, 2 or 2 days a week. In fact, I would agree with Wolff to this extent: 80 percent of the top 100 papers will not be seven-day papers 18 months from now (make that my first 2010 prediction).

In the hinterlands, 18 months from now, we’ll still find most of those 1200 or so small-town, small-city dailies — many with cuts in publishing schedules (to five or six days a week), paging, features, staffing or format, but carrying on as the voices of their communities. Those small dailies have the biggest opportunity, capacity and flexibility to innovate and find new models that can survive beyond the next year or two.  What they need is some leeway from headquarters to experiment so that some of them can discover the models that others can emulate. They need to be digital enterprises 18 months from now. If they don’t make that transition, plenty of new enterprises, including many with print components, will arise to show the way.

I just acquired a wood stove to cut down on my heating bills next winter. I expect to be starting the fires, for quite a few years, with newsprint delivered by my local small-town daily newspaper.

Image from Gawker.com

______________

*Per the most recent compilation available from NAA, which is dated 2007, but the mix doesn’t really change much over time.