Back in November, the Lab’s own Adrienne LaFrance wrote a number of words about Upworthy, a social packaging and not-quite-news site that has become remarkably successful at making “meaningful content” go viral. She delved into their obsession with testing headlines, their commitment to things that matter, their aggressive pushes across social media, and their commitment to finding stories with emotional resonance.

Things have continued to go well for Upworthy — they’re up to 10 million monthly uniques from 7.5. At the Personal Democracy Forum in New York, editorial director Sara Critchfield shared what she sees as Upworthy’s secret sauce for shareability, namely, seeking out content that generates a significant emotional response from both the reader and the writer.

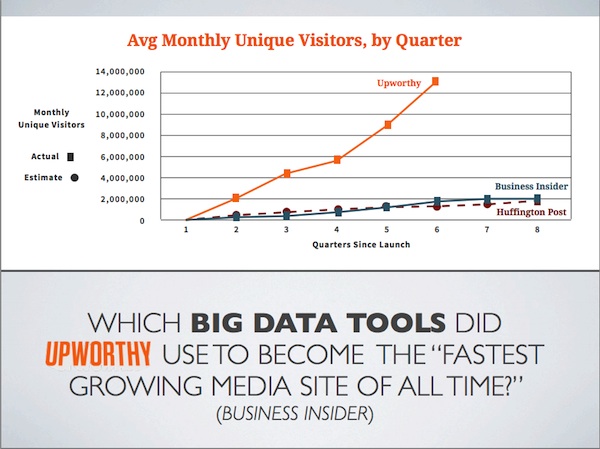

A slide from Critchfield’s PDF presentation.

Critchfield emphasized that using emotional input in editorial planning isn’t about making ad hoc decisions, it’s about making space for that data in the workflow, or “making it a bullet point.”

Here’s how she explained it:

When I spoke with Critchfield after her talk, she underscored the way in which packaging content is Upworthy’s bread and butter (most likely WonderBread and Land o’ Lakes [Sorry, Don Draper]).

“If you watch people shop in a grocery store, 95% of the time they are scanning the shelves for the packaging, making the choices on that before they turn the bottle around and look at the nutrition information. People choose their media that way too. So you can have a piece of media with the exact same nutritional value in it with different packaging and the consumer is going to choose the one that appeals to them most,” she said.

But before you can package content, you have to create it — or at least, select it from out of the vastness of the Internet. The people who do that are Critchfield’s handpicked team of curators.

“Of the things we curate at Upworthy, I think our editorial staff is what we pride ourselves the most on curating. We really focus on regular people. We reject the idea that the media elite or people who have been trained in a certain way somehow have the monopoly on editorial judgment, what matters or should matter. So we focus almost exclusively on hiring non-professionally trained writers,” she says. “To be honest, it’s sometimes difficult for folks who have professional background to come into Upworthy and have success.”

In other words, Critchfield builds the element of genuine emotional response into her team by hiring people who were never trained to worry about what’s news, and what isn’t.

“I tell my writers, ‘If you’re not feeling it, don’t write it.’,” says Critchfield. “We don’t really force people, we don’t let an editorial calendar dictate what we do. There will be big current events, and if someone on staff feels really passionate about it, then we cover it. And if there aren’t, then we don’t.”

The vast majority of Upworthy’s traffic comes from social media sites, where Critchfield says conversation is more valuable to the reader anyway. Some of their biggest hits have been about the economy, bullying and, recently, as displayed in her talk, funding cancer research after a young musician died of pancreatic cancer.

Critchfield says she encourages her curators to have huge vision for their posts. If they don’t expect it to get millions of views, then it’s not worth posting. Adam Mordecai is a great example of that kind of intuition, she says. He’s the guy who posted “This Kid Just Died. What He Left Behind is Wondtacular,” the video about cancer that ended up raising tens of thousands of dollars. (The original YouTube video got 433,000 Facebook shares; Upworthy’s got 2.5 million.)

Trained journalists are often rubbed the wrong way by the idea of writing headlines like that, or being asked to spend so much time on them. (Critchfield says instead of spending 58 minutes writing a story and 2 minutes on a headline, most journalists would be better served by spending 30 or 40 minutes on their piece and 20 to 30 on their headline. “People look at me and say that’s crazy, I don’t have time, I would never do that,” she says, “and they walk away all sad. That’s happened to me over and over again.”)

“I have a broadcast journalist who just came in and said, ‘Sara, I just can’t get over it. Every time I write ‘wanna’ in a headline, I feel like I’m going to hell,'” she says. “You have to match appropriately to the context. You’re competing — people on Facebook are at a party. They’re around friends, they’re trying to define themselves, they’re trying to look at baby pictures. You have to join the party, but be the cooler kid at that party. You’re not going to do it by speaking formally to people who are there to have fun.”

Fighting that training can be hard, which is why Critchfield has so carefully assembled team of “normal people.” “In the curation of the staff, I look for heart. What moves this person? There are people on staff — I have an improv comedian, I have a professional poker player, I have someone who works for the Harlem Children’s Zone, I have a person who used to be a software developer,” says Critchfield. “What they’re trained in isn’t as important as the compilation of a group of people with various hearts and passions.”

Or at least mostly normal people. Femi Oke was a radio producer when she decided to apply for a job at Upworthy. Oke says she was looking for a side gig that would give her experience with social media when she saw an ad for the job. “In typical Upworthy fashion,” she says, “it wasn’t a normal ad. It was a crazy ad — it was really intriguing.”

Oke describes going through an intensive training process at a retreat in Colorado where the curators learned to “speak Upworthy.” At first, she was surprised that the majority of the staff weren’t journalists, but soon the strategy of broadening the audience through diverse hires started to make more sense. But as the site’s popularity grew, Oke says it became increasingly important for curators to embrace traditional media tasks, like fact-checking. “As people started to see them as news, they started doing things news organizations would do,” says Oke. “They have such a fantastic reputation, they don’t want to ruin it.”

Since starting at Upworthy, Oke’s been hired to host The Stream, Al-Jazeera’s social media-centric daily online TV show, a concept born out of the Arab Spring. “At the end of each show, we have a teaser for what we’re doing on the next show. It would be a really heavy, intense, stodgy but accurate breakdown of what the next day’s subject is. I walked in and said, if we can’t make it a one-liner where I’m going to watch the show tomorrow, we shouldn’t be writing that,” Oke remembers. “My producers said, ‘Oh my god, she’s crazy.'”

So for a show on the 50th anniversary of the African Union, she might say “Happy 50th birthday, African Union! Are you looking good — or do you need a makeover?”

“That’s me anyway, but Upworthy made me even more certain that that was the style of broadcast that works for all media. It’s about being inclusive, accepting, and inviting people in.”

The one thing Critchfield says brings all the curators together is their competitive spirit and obsession with metrics. All Upworthy curators have direct access to the analytics for their work, and she says they are obsessed with testing different tricks. (How many more people will click this story if there’s a curse word in the headline?) But Critchfield says no post gets published without gut-checking its author to see how committed they are to the larger cause it’s meant to represent.

“We’ve really clarified internally that we can’t separate data analytics from human editorial judgment. Working to combine those two together is sometimes difficult,” she says. “What makes a thing viral can have just as much to do with how the person writing the piece up or working with the piece feels about it as it does with big data or listening tools.”

Photo by Esty Stein / Personal Democracy Media used under a Creative Commons license.