Not many people remember it now, but the Atlanta Journal-Constitution was one of the leading pioneers of the early Internet age. It was the first newspaper on the Prodigy Internet service — one of America Online’s two main competitors back in the early 1990s — and within 90 days of launching its Access Atlanta service, it had twice as many online subscribers, 15,000, as any other newspaper in the country. Eight months after launch, Neil McManus wrote in the magazine Digital Media that all other newspapers interested in pursuing a digital strategy should visit Access Atlanta “with notebook in hand.”

But that was the apex. Prodigy’s membership stopped growing, crushed by the less staid and more freewheeling America Online, and within a year and a half the AJC was forced to end its association with Prodigy, turning to the web later than many other large newspapers. Because the company viewed the digital strategy as a supplement to the print product rather than an eventual replacement, the paper did not see the web as an impetus to change its print-based business model. In short order, the pioneers became also-rans.

Obviously, the Journal-Constitution bet on the wrong horse — and, in this case, the wrong technological platform, since after AOL drove Prodigy and Compuserve out of business, the World Wide Web rendered AOL’s proprietary service irrelevant. But it’s hard to fault the Journal-Constitution for failing to predict the future correctly. After all, nearly every newspaper failed in that. Even though the AJC guessed wrong on the answers, its management and editorial staff asked a lot of the right questions. And they placed a decent-sized bet on their guess.

At the time of Access Atlanta’s launch on Prodigy in March 1994, AJC technology columnist Bill Husted interviewed Internet analyst and provocateur Josh Harris about the newspaper’s moves. Harris believed the paper was on the right track, though he sensed (probably correctly) the lack of organizational urgency regarding the venture.

“In about six months, all your key management will be saying, ‘Why didn’t we do this five years ago?’” Harris told Husted. “This project was cigarette change for Cox. I don’t think they believe in their guts, or their wallets, in what they’ve done. In time, they’ll see what a smart move they made.”

“In about six months, all your key management will be saying, ‘Why didn’t we do this five years ago?’”

Harris was right. Even though partnering with Prodigy was a bad decision, investing serious money in a unique electronic identity was a smart move. In some ways, the Journal-Constitution’s digital rise and fall mirrors that of the San Jose Mercury News, which Michael Shapiro wrote about in the November/December issue of the Columbia Journalism Review. The Merc started out on AOL but quickly abandoned it to build its own website, Mercury Center, which quickly became one of the indispensable sites for Silicon Valley — but then crested and cratered along with the rest of the newspaper industry.

The Journal-Constitution had a number of smart people pushing it forward, including director of information services Chris Jennewein, who left Atlanta to perform a similar role at the Mercury-News, and webmaster Chad Dickerson, who is now the CEO of Etsy. The AJC and Cox had enough clout within the news industry for their executives to be able to persuade other papers, including the Los Angeles Times and Newsday, to make similar deals with Prodigy.

And they had enough clout for a Cox executive, Peter Winter, to become the interim CEO of the New Century Network, the industry’s abortive 1995 attempt to form a web cartel and control access to their journalism. But the collective was sunk by the inability of all the principals — including Cox, Knight-Ridder, Advance, Tribune, Times Mirror, Gannett, Hearst, The Washington Post Co., and The New York Times Co. — to agree on strategy. The failure of the New Century Network prefigured the web woes that each company would experience in the decade to come.

The idea of digital newspapers had been around for a long time. Going back to the 1970s, decades before Craig Newmark started Craigslist and eroded newspaper dominance in classified advertising, newspaper companies realized that their business models depended on preserving their monopoly on classifieds — and they were afraid that a new competitor could weaken that position through a new technology.

So, in the early 1980s, the Associated Press led a number of newspapers (including the AJC) in an 18-month experiment in digital newspapers hosted on an early version of Compuserve.

So, in the early 1980s, the Associated Press led a number of newspapers (including the AJC) in an 18-month experiment in digital newspapers hosted on an early version of Compuserve.

But not many people had access to modem-enabled personal computers in those days — Compuserve had around 12,000 subscribers across the country — and the low audience and difficulty of using the cutting-edge technology paradoxically led most of the newsmen to affirm, rather than challenge, the status quo. “They perceived it as less of a threat after having been party to it,” said Henry Heilbrunn, an AP executive who led the experiment.

Chris Jennewein was an early advocate for the Journal-Constitution’s digital future. In the late 1980s, he started working on audiotex and videotex, two technologies aimed at combatting the informational time lag associated with a daily newspaper.1 The first was an automated system of phone numbers that would allow users to call for up-to-the-minute stock prices, sports scores, and weather reports. The second was a primitive dialup system that would allow them to check out news archives and the next morning’s classified ads.

Beginning in 1990, the AJC dialup service was called “Access Atlanta,” and rather than following the phone company’s paradigm of per-minute pricing, they charged a flat $6.95 a month for it. (That was the same price that they would charge four years later, when they launched on Prodigy.) In the meantime, flush with cash, the company was in the mood for experimentation. “[It’s] a classic skunk-works venture,” said Cox executive vice president Jay Smith in 1993. “We put our toe in the water.”

The technology was ahead of the consumer base, but that was fine with Cox. “Archives, movie reviews, primitive email, primitive chat, and we had, most interestingly, the business section up early at 9:00 pm the evening before,” Jennewein told me. “I think at the height we had 600 subscribers.”

In late 1992, the AJC decided to move Access Atlanta from an in-house operation to a third-party service. Cox looked around and even considered purchasing Prodigy, which was number-one at the time, with more subscribers than either Compuserve or AOL. Prodigy also offered the newspaper a far larger cut of subscription revenue than AOL was willing to offer, and far greater flexibility for the paper to create its own branded version of Prodigy’s software.

Access Atlanta was a proprietary service on a proprietary service: Subscribers could pay either the standard $6.95 a month, or if they subscribed to Prodigy for $9.95 a month, they could add Access Atlanta service for an additional $4.95 a month. But while the service itself was getting appreciative nods around the news industry, Prodigy’s growth was already stalling.

One reason is that, unlike those of America Online, Prodigy’s executives wouldn’t allow unmoderated bulletin boards, requiring that every user comment be edited before it was published. Another was Prodigy’s retail strategy, influenced by its corporate parents, Sears and IBM. Unlike America Online, which targeted computer manufacturers to install AOL software on new computers and flooded mailboxes with a seemingly infinite stream of AOL disks, Prodigy sold its software in stores — and separately branded Access Atlanta software was also sold for people who didn’t want to subscribe to Prodigy. Retail was hardwired into Prodigy’s corporate culture. As Fred Lowy, who headed the Access Atlanta team over at Prodigy, explained to me: “The hidden agenda was always to promote IBM and Sears.”

“I was thinking, ‘Who are these people who signed up with Prodigy? No one uses Prodigy. Everyone uses the web.'”

As the first paper on Prodigy, the AJC had an incentive to try to get other newspapers to join the service, so that more readers would want to subscribe. Cox moved all the papers it owned over to Prodigy and also worked on persuading selling other newspaper companies to join them. They were successful with Times-Mirror, which owned the Los Angeles Times and Newsday. They had been on the cusp of a deal with America Online, but switched to Prodigy after a successful eleventh-hour pitch by Cox.

Cox, Times-Mirror, and Prodigy soon formed what they called a “newspaper alliance,” in which Cox and Times-Mirror would get a cut of the proceeds whenever a new paper signed up with Prodigy. But the partnership was already nearing an end. When Access Atlanta was launched in March 1994, its publisher, David Scott, announced his hopes of obtaining 10,000 subscribers by the end of the first year and 40,000 by the end of the third. It reached the first milestone, announcing its 20,000th subscriber in August of 1995. It awarded twenty free months of service to the lucky 20,000th customer, Seth Ehrlich.

It never reached a third year, though, and Ehrlich never got all twenty months of service. Prodigy had fallen behind Compuserve and AOL by late 1994, and subscriptions had plateaued for both Prodigy and Access Atlanta. Finally, the Journal-Constitution moved Access Atlanta off Prodigy and onto the free World Wide Web in late 1996.2

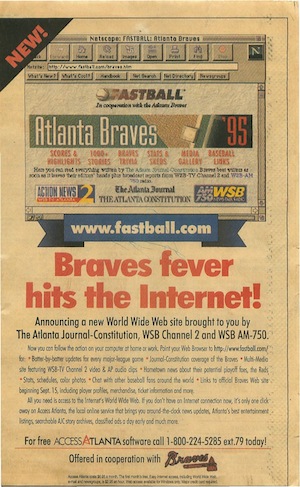

Before that happened, the newspaper had very little content on the web. The Access Atlanta team was kept separate from the web team, which maintained a barebones placeholder at www.ajc.com that linked to several other websites the newspaper created, like a baseball-focused one called fastball.com. The newspaper also maintained other sites that it didn’t link on its front page, including a Southern humor site called yall.com and a sex humor site called brazenhussy.com.

Chad Dickerson was hired out of college in 1995 as a webmaster for all the newspaper’s content that was not on Access Atlanta, and he could see that restricting online access to proprietary subscribers was limiting growth. “I had just turned 23,” Dickerson told me. “And I was thinking, ‘Who are these people who signed up with Prodigy? No one uses Prodigy. Everyone uses the web.’ That was what motivated me to get them out of this stranglehold.”

At that point, the newspaper started putting its content on accessatlanta.com, but the site was maintained more as a neighborhood and lifestyle portal rather than as a breaking news site. So, in 1998, the newspaper launched AJC.com as its news site, and ever since then, the newspaper has operated both accessatlanta.com and AJC.com.

After spending most of the decade selling subscriptions for its online content, the newspaper offered its web content entirely free. But the newspaper was still so overwhelmingly profitable that the change in online revenue streams hardly made a dent — and hardly mattered. And that was hardly surprising, said AJC.com editorial director Hyde Post. “How many folks are willing to think, ‘I’m gonna make a decision that’s gonna cost me $100 million on the newspaper side, in the hope that I’ll get it back in five years on the other side’?”

“I think the industry could see the future, but were not prepared to take the risks,” said Heilbrunn, the former AP and Prodigy executive. “The newspaper industry looks at itself as a local franchise with a local brand, but isn’t willing to step out of that particular perception so that it invents Monster.com for employment ads or Zillow for real estate. There were a lot of opportunities for individuals or industry to do these things.”

Though the Access Atlanta brand name survives in a website and a free weekly paper, the pioneering Internet service remains nearly forgotten today.

Access Atlanta was a way to re-imagine the Atlanta Journal-Constitution on a new platform, but it could never replace the print newspaper’s revenue stream. “Except for the forward-looking groups, it was the old railroad paradigm,” said Fred Lowy. “‘We’re not in the transportation business, we’re in the railroad business.’” And that applied all the more to advertising revenue. Dating back to the 1970s, newspapers thought they were in the classified ad business, when they were actually in the much broader business of serving their communities by connecting people with the information, news, products, and services that they wanted. Cox made a few savvy investments in the new world order, such as founding AutoTrader.com. But neither Cox nor its competitors made those types of moves with any kind of urgency.3

Back when Cox was flush enough to afford spending money on a skunkworks, Access Atlanta could be brilliantly innovative. But when it became clear that the market had shifted, the Journal-Constitution was caught on its back heels, and it didn’t have the same financial cushion as before to continue to innovate from comfort. And though the Access Atlanta brand name survives in a website and a free weekly published by the AJC, the pioneering Internet service remains nearly forgotten today, so that as of this writing, it does not even have a Wikipedia page.

The Journal-Constitution could not predict the changes in their business that the Internet would bring about; few did. The newspaper industry failed to take advantage of Web 1.0, and a decade later, it failed to take advantage of Web 2.0, standing by as social media redefined how people learned what was happening in their communities and in the world. If large news organizations want to survive the next wave of technological change, they will need to do more than just dip their toe in the water. They will need to dive in.