This is the important part: Read the post below for more details if you’d like, but the important thing here is that we’d like you to take a brief survey to help us better understand how press passes and other media credentials are being issued today.

→ → → This is the link to click. ← ← ←

Taking 10 minutes or so will help us understand the current state of play and help us identify what further action we can take. And we want to make sure we get responses from a wide variety of newsgatherers — journalists at traditional news organizations, bloggers, citizen journalists, and more. Thanks for your help.

In an earlier era, “who deserves a press pass” wasn’t that complicated a question in the United States. The title of “journalist” generally went to people who worked for a specific subset of news organizations — newspapers, wire services, television stations, radio stations, magazines. There might be some questions on the edges regarding freelancers, but for the most part, it was settled territory.

But with the web’s democratization of the power to publish, access to press credentials has become contested ground. Can a police department choose to keep a local news blogger from crossing police lines? Should a nonprofit news organization have the same access to the Senate gallery as a for-profit one? Should a citizen journalism project have the same access to government office space as a newspaper?

In other words, the institutional infrastructure that surrounds journalism hasn’t always kept up with the changes in the field itself.

A number of institutions that care about journalism — the Digital Media Law Project, the Investigative News Network, the National Press Photographers Association, Free Press, Journalist’s Resource, and us here at Nieman Lab — have teamed up to try to understand where American institutions (both governmental and private) stand on these issues. And to do that, we’re asking you to take a brief survey to tell us your experiences.

Here’s an introduction to the project:

Even as the very concept of journalism evolves to accommodate dramatic new ways of gathering and interacting with information of critical public importance, the idea of media credentials remains deeply embedded in the practice of journalism in the United States. Dozens of laws at both the state and federal levels condition the right to engage in newsgathering activity on the receipt of credentials; police departments use press identification to separate journalists from protestors subject to arrest; and political parties limit access to vital aspects of the democratic process to those approved by campaigns. And yet, systemic understanding of credentialing practices and standards is very poor, with public attention normally being limited to discrete issues as they arise.

“In many ways, newsgathering rights in the United States are a structure built on shifting sands,” said Jeff Hermes, director of the Digital Media Law Project. “It is crucial for the future of journalism that we learn more about how these rights are allocated by those who control access.”

The new study is designed to develop a nationwide overview of credentialing practices over the last five years, in order to identify emerging norms and systemic issues in how credentials are used by government entities and private organizations to control newsgathering activity. The core of the study is an online survey that asks journalists and others who gather and report information of public importance to provide information about their experiences in applying for and obtaining media credentials from federal, state, and private entities in the United States. The survey will generate data that can be made available to the public, be used as a platform for further study, and form a basis for developing measures to improve conditions for journalism as a whole.

We welcome participation in the survey from all who consider themselves to be involved in gathering news for publication, including professional and citizen journalists, activists who publish news content as part of their activism, and independent bloggers who write about current events. If that sounds like you, you can take the survey at http://www.dmlp.org/survey. We hope you will join with us in this effort!

For this research to be reflective of reality, we need a broad selection of people to participate. And in particular, I want to make sure we have a broad selection of Nieman Lab readers, since so many of you work for the kinds of new news organizations that can sometimes get caught in these gaps.

So: Please take the survey. You’ll be helping journalism.

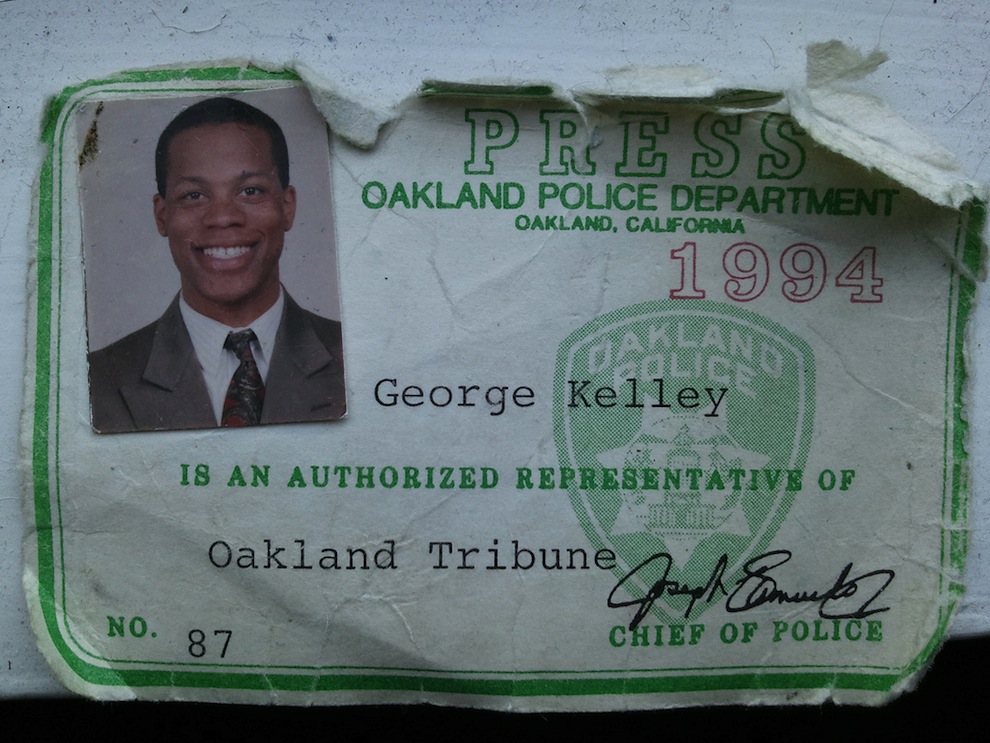

Photo of an Oakland PD press pass from 1994 by George Kelly used under a Creative Commons license.