Have you bought a lonely single copy of a newspaper lately, from a newsstand or a newspaper box? Probably not. Neither are many other people.

Single-copy newspaper sales — which not that long ago made up as much as 15 to 25 percent of sales — are obsolescent, dropping in double digits per year and, for many papers, 25 to 50 percent or more in just the past three years. Single copy is just one corner of a disappearing world, and it’s one we’ve paid little attention to. In its decline, though, we can see the print-to-digital transformation from another angle.

Why the drop? Of course, digital reading is a prime reason, propelled by the smartphone revolution; more than one billion smartphones were shipped for sale around the world last year, a mind-boggling number.

But it’s not the only reason. Right up there on the list would be newspaper company strategy, as expressed in its pricing decisions. Call it quarteritis — a piling on of quarters, raising single-copy prices from 50 cents to 75 cents and then to a dollar and more.

Publishers have applied the same pricing theory to both home delivery and single-copy selling over the last four years or so: Get a lot more money from somewhat fewer readers, and come out financially ahead overall. In revenue, the theory has worked, driving flat-to-positive circulation revenue in a time of declining subscriber bases — though publishers’ pricing power may have peaked quite quickly. Look at a company like Gannett, whose circulation revenue was down 0.9 percent for 2014, despite — or because of — some of the most aggressive price increases in industry. Gannett’s 25 percent-plus price increases for home delivery aren’t unusual for the industry.

The upward pricing of newsstand copies across the industry has also been dramatic, as measured by the Alliance for Audited Media last year. For the first time, the most common price for a daily newsstand paper hit $1; the most common price for Sunday is now $2.

These higher prices have driven these major single-copy declines. They prompt a major question: Has the newspaper industry further accelerated its own decline through its shock treatment of single-copy buyers?

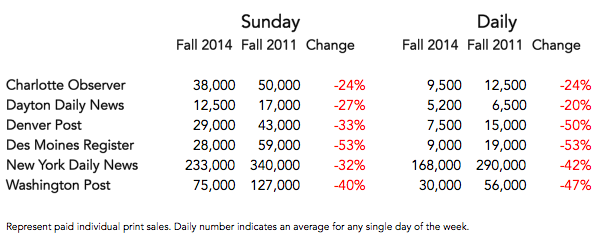

Let’s take one of Gannett’s largest papers, the Des Moines Register, once a must statewide read for the civically involved. On an average weekday, it sells just 9,000 single copies. For both Sunday and daily, it has lost 53 percent of its single-copy sales in just three years. Its home delivery sales have dropped substantially as well over the same period, down 23 percent on Sunday and 14 percent for daily. Still, the rate of single-copy loss runs double to triple that of home delivery.

It’s a pattern that repeats itself in the data.

Let’s take a paper recently put up for sale, Mort Zuckerman’s New York Daily News. It too has seen sharp drops in single-copy sales, 43 percent daily and 32 percent on Sunday — again, in just three years. Its daily home delivery decline over the same period (20 percent) is only half as bad as its single-copy one. (It’s a cruel irony that the only thing that can make their home delivery loss look decent is the size of their single-copy loss numbers.)

We see the same pattern of loss elsewhere — reaching 50 percent or more for the Register and the Sunday Denver Post, with The Washington Post showing losses in the 40 percent range. Even the smaller market Charlotte Observer and Dayton Daily News show 20 percent-plus losses over the last three years.

It’s curious — and maybe indicative of the newspaper industry’s woes — that it’s nearly impossible to get an apples-to-apples comparison of single-copy volume (number of copies sold) and revenue over the past decade. Some reporting systems have changed, and much of the data is piecemeal, obscuring our — and the industry’s own — understanding of what’s happening. There’s much good data work in progress at the Alliance for Audited Media, Inland Press, and the Newspaper Association of America, but not a lot in this area.

NAA’s survey of members last year provides the best window into the overall loss — and its key driver. The volume of sales loss generally correlates directly with higher pricing, says John Murray, the Newspaper Association of America’s vice president for audience development. In general, the greater percentage price increase, the greater the loss in volume: “If you don’t price up, it’s at most 5 percent erosion,” he says.

Think back to the days when a cup of coffee cost 50 cents and the morning paper half as much. For less than a buck total, you could browse through the day’s news at your leisure at the corner coffee shop — days that seem as faded as Garrison Keillor’s private detective Guy Noir on Prairie Home Companion.

Today, stop by Starbucks on a Sunday morning, and a cup of artisanal joe and a Sunday Times may well set you back more than ten bucks.

In the digital-reading era, single copies of magazines have tanked as well. Take newsmagazines, the once-healthy sector dominated by Time, Newsweek, and U.S. News and World Report. In 2008, newsmagazine single copies lost 11 percent of their sales in a single year. In no year since have they lost less than 8 percent; in 2013, they lost 10.4 percent.

Overall, U.S. magazines lost 14 percent of their newsstand sales last year, part of a vertiginous and one-way decline. The bankruptcy of one large newsstand distributor contributed, but then again, when things start going south in a business, the collateral damage just cascades.

So let’s return to the why.

NAA’s data shows that pricing makes a major difference. The detail of that pricing may surprise you. 44 percent of U.S. dailies now charge $1 for a weekday paper, according to a 2014 AAM 2014 study, while 39 percent charge 75 cents. It wasn’t that many years ago that 50 cents replaced a quarter as the standard. And five years ago, half (48 percent) of newspaper publishers charged 50 cents; now only 15 percent are at that price.

For Sunday editions, $2.00 is the prevailing charge, with 40 percent of dailies using it. Another 28 percent charge $1.50. 12 percent of Sunday editions are sold for more than two dollars.

We have to ask how long an industry can offer less and less and charge more and more.

What’s happened in newspaper pricing is that too many publishers have doubled their prices while halving the size, and quality, of their products. I can’t think — nominations invited — of other industries that have done that with longer-term success.

It’s like selling a 20-ounce bottle of Coke for a buck — and then three years later hawking a 10-ounce bottle for two dollars.

We can tick off a few other reasons for single copy’s dramatic drop. One is self-fulfilling: With fewer rack sales per location, and a keen eye toward cost reduction, newspaper companies then gradually decrease the number of locations selling single copies — improving ROI but limiting availability.

Then there’s the old coin combination theory, about which any old circ hand can wax on about. What kinds of coins do you have in your pocket? Demanding more quarters of the single-copy buyer now on the hunt for a paper puts just one more barrier up to a sale. (Americans are light years behind our Nordic friends in embracing the cashless economy.)

So this single-copy decline is, at least in part, heavily self-inflicted. The industry’s gains in overall circulation revenue — driven by those broad price increases for both home delivery and single copy — has been an important offset against declines in print advertising. Is that a smart strategy?

We know that the circulation revenue gains — as measured by NAA — have been real, 3.7 percent in 2013 and 5 percent in 2012. (2014 data will be out in May.) That added revenue has salved the painful hurt of deepening print ad decline — not offsetting it, but helping to ease the trauma. But if it’s only a two- or three-year balm — if numbers like Gannett’s 0.9 percent decline start to be seen more widely — too-aggressive single-copy pricing may be a prime suspect.

From the data we have, it’s tough to know how much of those circulation revenue gains have been driven by home delivery vs. single-copy sales. What is clear: By trading off volume of papers sold for added revenue, the industry has narrowed its most loyal customer base. (And, yes, fewer copies sold at higher prices does save on manufacturing costs. Still, circulation declines don’t make for good strategy for an industry that badly needs reader customers.)

It would make sense that single-copy buyers would make up one of the most qualified sets of would-be digital buyers. In that funnel of potential digital subscriber acquisition, occasional single-copy buyers would have to be considered good prospects. Clearly, they like the news brand. They buy it, at least once in a while. And they, like almost everyone else, are transitioning, however slowly, to digital news.

Perhaps the big trade-off of more revenue for less volume — fewer customers — is a smart one, and you can make the case that publishers had little choice. In the medium term, though, they’ve clearly pushed aside some print readers who might have transitioned over to paid digital or all-access subscriptions.

Why does that matter? Most of the new circulation revenue we’ve seen associated with paywalls comes from print readers paying a little extra, either as part of single print/digital bundle or as an upcharge. So the industry has narrowed its likely subscription prospects, even as it’s benefited in the short term from more revenue. That becomes even more problematic if, as I believe, the industry’s final 2014 circulation revenue increase will slow further — or possibly even turn negative — just three years into the paywall game.

There’s one other financial impact of single-copy loss: preprint ad revenue. It’s true that some big-box advertisers have been cutting back on preprints in single copies, but they still constitute important revenue overall. With other ads declining, those circulars for Macy’s and Best Buy now contribute a larger and larger part of ad revenue. What do you do with circulars? You insert them into papers, and if you’re selling fewer single copies, preprint orders necessarily decline, reducing revenue. Publishers can offset some of that decline by putting circulars into free “Sunday Select” distribution, but that may only mitigate the loss.

Step back from the nuances of pricing and volume, and we see the larger prism of reading change. The airport magazine stands and big-city kiosks all feel the loss. Tablets and Kindles have made a dent in print magazine buying; smartphones not only offer more news choices than any single print paper, but — let’s remember — they offer today’s news, not yesterday’s. We do indeed live in a swirling world of “single copies,” but they’re stacked atop each other in almost infinite depth, though only millimeters deep, on our phones. In Internet mythology, the second copy is free — but in the world of still needing to pay journalists to produce that first copy, somehow those second, third, and subsequent digital copies must be accounted for.