Editor’s note: Matt Carlson of Saint Louis University and Seth Lewis of the University of Minnesota have a new book out called Boundaries of Journalism: Professionalism, Practices and Participation. In it, they argue that understanding the nature of boundaries in journalism is essential for understanding how certain people, types of work, and ways of thinking in journalism become accepted (or not) — and why that matters for the changing nature of news.

Their edited book includes chapters from several academic friends of the Lab, including C. W. Anderson, Mark Coddington, and Mike Ananny, and covers a range of issues at the intersection of journalism, sociology, and emerging tech. Here’s an overview of the book.

After hearing about the topic of our new book Boundaries of Journalism, one of Matt’s colleagues stopped in to chat. He had just had a hotly contested debate over whether television sports reporters counted as journalists. He was making the argument that they did, and he looked to Matt apparently to sort things out.

If only it were as simple as consulting some master table to provide a yes-or-no, in-or-out kind of answer! But playing referee is not what is interesting about studying the boundaries of journalism. Instead, what’s much more vital is looking at the messiness and asking: Just what are we fighting over?

If only it were as simple as consulting some master table to provide a yes-or-no, in-or-out kind of answer! But playing referee is not what is interesting about studying the boundaries of journalism. Instead, what’s much more vital is looking at the messiness and asking: Just what are we fighting over?

We came to the book because we were both interested in the same questions about boundaries. Readers of Nieman Lab are well familiar with the parade of new faces and ideas about journalism accompanying the rise of digital media. But what does it all mean? And how can we study it?

We saw the need to clarify how to think about boundaries, and we enlisted an international cast of journalism scholars to help. Before getting into what we wrote, it is important to start with why we wrote it. Exploring the boundaries of journalism is not an intellectual exercise relevant only to those of us in the academy. Definitions matter, because how we think about the issue of boundaries has real consequences. Matt makes this case in the introduction to the book:

Gains in symbolic resources translate into material rewards. Being deemed a “legitimate” journalist accords prestige and credibility, but also access to news sources, audiences, funding, legal rights, and other institutionalized perquisites.

To take one prominent example: Resistance to including blogging under the umbrella of journalism seems as much an artifact of the early 2000s as Nelly’s “Hot in Herre.” But even now, the issue is not settled. The merits of blogging have become a current topic of debate in Australia as a matter of who is eligible for legal protections ordinarily afforded to journalists. Closer to home, the indispensable SCOTUSblog continues to have its Supreme Court accreditation blocked by the panel of journalists who handle credentialing for the U.S. Senate (to which the high court defers). Despite its reputation, the sites lacks basic privileges — like guaranteed access and office space — given to other news agencies.

Certainly, boundaries have practical consequences, but they’re also important on a deeper level. After all, boundaries organize our world for us; we rely on distinctions to make sense of how we know about reality. Or, as Seth puts in the epilogue to the book:

To set the boundaries of a particular place, process or, in this case, profession is to claim a kind of mapmaking authority: to succeed in marshaling the resources necessary to lay claim to a certain space and impose a particular vision about the character, meaning, and distinctiveness of that space.

In other words, the study of boundaries provides a cartography of society. From this viewpoint, questions quickly spring forth: Where are boundaries around journalism drawn? Who makes these distinctions? How do boundaries get made? What are their consequences?

To look at boundaries in a systematic way, we take as a starting point Thomas Gieryn’s pioneering work in the sociology of science. To Gieryn, the boundaries of science emerge out of conflicts that he calls “credibility contests” in which the establishment of borders relates, at core, to the question of legitimacy. Take, for example, the once-admired discipline of phrenology: Its ousting from Science with a capital S both diminishes its practice while protecting other scientific practices. All of this takes place through what Gieryn calls boundary work.

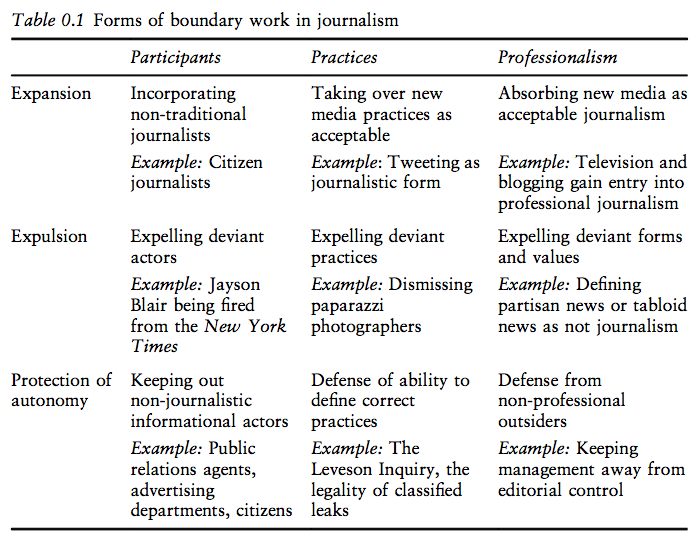

Boundary work is complicated, Gieryn’s work shows. It doesn’t just cut one way. In his book Cultural Boundaries of Science, Gieryn breaks boundary work down into the three categories. In the realm of expansion, one field invades another, taking over its domain. For example, childbirth was long the province of midwifes before being brought under the tent of traditional medicine. By contrast, expulsion leads to the shrinking of boundaries to cast out some practice considered to be unscientific — phrenology, again. The third category, protection of autonomy, concerns the maintenance of control against would-be intruders. In our present age, this can be seen in Congress’s meddling with the affairs of the National Science Foundation.

So, how do we use Gieryn’s ideas to talk about journalism? First, we have to admit that journalism is not science. News has always been more porous, with few formal mechanisms to draw a line between insiders and outsiders. Once we accept this, we can find use for Gieryn’s model. The introductory chapter of Boundaries of Journalism includes the following table, which combine’s Gieryn’s categories with our own topics relevant for studying journalism: participants, practices, and professionalism.

The first two columns differentiate between people and their practices. They get to the who and the what questions. Much of what we think about journalism is really about journalists — who is it that we call upon to report the news? To be a journalist is to be accorded certain rights and recognition. But journalists are also expelled too, as the history of journalism’s scandals shows. Meanwhile, debates swirl around acceptable practices regardless of who is doing them. This can been seen in the questions surrounding how journalists use social media.

The third column, professionalism, gets to the heart of what makes journalism legitimate. By and large, the dominant model of responsible news is that of the professional journalist beholden to ethical norms, rules of practice, and expectations of autonomy. This column gets to the beating heart of journalism; it is where its core identity is forged and contested.

Taken together, this table demonstrates the wide range of activities falling under the umbrella of the “boundaries of journalism.” The chapters in the book explore these and other dimensions, including boundary questions connected with everything from entrepreneurial journalism and native advertising to social media verification and wearable technologies — all toward advancing our thinking about how journalism is changing and what it means. The only clear conclusion is that boundaries will continue to be drawn, erased, and redrawn, each iteration altering how we think about news.

Matt Carlson is an associate professor of communication at Saint Louis University. Seth C. Lewis is an assistant professor and Mitchell V. Charnley Faculty Fellow in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities.