Mansfield, Ohio’s story is a common one. The Rust Belt city, located about halfway between Cleveland and Columbus, has endured many of the same economic troubles that other industrial Midwestern cities are facing as manufacturing jobs disappear.

But Mansfield is more than its industrial decline. In 2013, Carl Fernyak, the CEO of local printer and copier supplier MT Business Technologies, founded Richland Source, a for-profit online news site covering Mansfield and the surrounding Richland County.

As Jay Allred, the site’s publisher, describes it, Fernyak was inspired to start Richland Source after participating in a Chamber of Commerce leadership program that asked participants to go out into the community and learn what was impeding growth in Mansfield. Many of the people Fernyak talked to wanted an improved media ecosystem.

“He really made the decision that day,” Allred said. “He said, ‘We need something that tells the story of Mansfield in a more complete way.'”

Allred joined the company in May 2013, and the site began publishing that June.

The Source is not yet profitable, but it is on track to generate over $500,000 in revenue this year — up from last year and ahead of projections. The site has nine full-time employees, two part-timers, and a small network of freelancers. It averages between 85,000 and 100,000 unique visitors per month, Allred said.

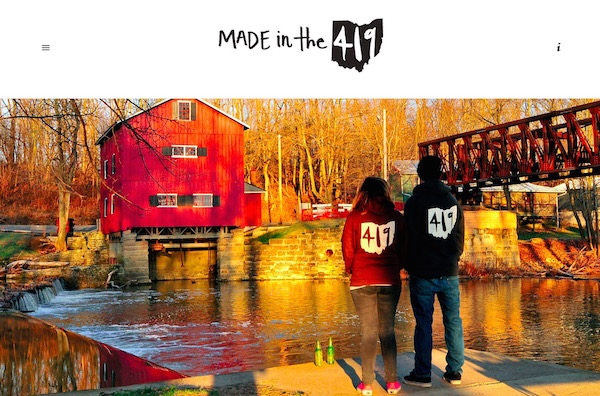

The vast majority of Richland Source’s revenue comes from advertising, though the site is diversifying how it makes money. Last year, for example, it launched Made in the 419 to sell apparel designed and made in northwest Ohio (which uses the area code 419 — hence the name.)

I spoke with Allred about the Richland Source’s business model, how it’s diversifying its operations, and how it plans to build a membership program. Here’s our conversation, lightly edited and condensed.

The way we reach out is pretty simple. I use the word “team” a lot, but in our context it’s really not corporate speak. The content we produce drives our success as ad sales people. When we started, we didn’t have an audience. But we had 15 advertisers on board before we even launched. The reason we were able to do that was that we went out to potential advertisers who had a stake in the community’s success — banks, hospitals, institutional advertisers — and told them what we were going to do. We offered them very reasonable rates.

It was very intentional on our part that this created pressure for our editorial team on day one — that we had advertisers and revenue coming in and that we were going to tell the story of the community in a constructive and proportional way, without living off the blood of the wounded. We didn’t want to chase pageviews through crime, blood, and drugs.

In the first six to nine months, we found that the community reacted very positively to our content. It didn’t necessarily generate massive pageviews, but the reaction to it was very real. I spent $150 on Richland Source t-shirts for our journalists, and they were actually proud to put them on. Those little signals told us that the content we were producing made people feel valued, and that we were a constructive force in their community.

That allowed us to build. We started to have some verifiables that we could bring back to our existing or prospective customers — our Facebook growth, our engagement numbers, our top 10 stories.

Our advertisers realize that they could probably buy their CPMs for less on a programmatic exchange — they could reach a larger audience through more established media in town. But they want to be associated with us because they value the attitude and the engagement of the audience that we’re reaching. That’s been crucial. We’ve been able to cultivate an audience that expresses its opinions, particularly on social media, in a way that’s demonstrably different from the way they express their opinions on our competitors’ websites. Advertisers notice that.

That was really important to me. If there’s an editorial initiative coming up, [editorial will] invite the business side into the meetings. On the business side, when we do things like sales promotions, we see what ideas the editors have for creating content that advertisers might buy into. Are there sponsored content opportunities that could supplement editorial content that maintains its independence? We’re very mindful about cross-pollinating, all the time.

I read The New York Times report on innovation. The thing that struck me most was the division and the hostility between sales and editorial in the old New York Times. I thought: My God, how did they accomplish things? Of course, it’s through the sheer scale and prestige of being The New York Freakin’ Times. We just knew we couldn’t be that way or we’d end up eating ourselves. So we’ve always been very careful to respect and admire the job that either side does.On the advertising side, I hammer into our sales people that if editorial doesn’t do the job that editorial does, then you have nothing to sell, so your job is to do every single thing you can to support the editorial team. And I tell the editorial side that if the sales people don’t sell ads, then I can’t pay your salaries. We have to work together. When we bring on a new team member, that’s part of the hiring process. We explain, and we ask them open-ended questions on how they feel about collaboration.

Out of respect [to the journalists], we essentially create a time block, so if [an editorial person] spends four hours on something, those four hours get charged to the business side, not the editorial side. That helps the editorial side get over the fact that sales asked them to ghostwrite a piece of sponsored content. They can say, “For 40 hours a week I was a journalist, but for four hours I worked for an in-house PR agency, and that cost got billed to the business side of the house.”

We don’t do that very much any more, though, because as we’ve grown we’ve been able to afford to move a person who was in editorial but had a social media and PR background onto the business side. All the sponsored content we do now runs through the business side unless we’re just jammed and need the help.

We reached out to every high school in our coverage area and said we wanted to donate popcorn bags to their concession stands for the entire school year. Fifty thousand popcorn bags cost about $5,000.

Last year was our first year doing this and we couldn’t get any advertisers to sponsor the bags because it had never been done before, so we had to go at it alone. In that case, we sunk $4,000 into it.

This year, we turned a $4,000 cost into a profit. We went out to advertisers that had an interest in the high school audience. An ophthalmologist bought a small portion of the bags, a driving school bought a huge portion, and the Air National Guard, which wants to recruit kids, bought a huge portion. We completely sold out. Now, every time a high school has a game and someone buys a bag of popcorn, Richland Source and one of its three advertisers reaches a crucial, targeted audience member.

No one else is doing that. We want to have advertising streams that are unique and not tied to banner ads, but that allow our advertisers to reach people in creative ways.

We try to tie everything we do back to our core missions, which is to tell a constructive and proportional story about the region that we cover. Made in the 419 gets more interest than any other thing we do — even though I’ll tell you it generates the least amount of revenue; we’re basically break-even on it.

In places like Detroit and Cleveland, little clothing companies have sprung up that sort of raise the collective middle finger to the rest of the country. [People in these regions] have endured a slow-motion, 25-year ass-kicking, and we’re kind of done with it. There’s a generational shift happening right now: People in their 20s and 30s don’t remember what it was like when it was good. They only remember when it sucked. So it can continue to suck, or they can make it better.

We saw that Detroit and Cleveland were making cool stuff that people were buying and wearing, that doesn’t look like it came from some committee or some Chamber of Commerce. We did some market research in the 419 area code, which is a really large geographic swath of Ohio, and there was nothing — we couldn’t find anything Made in Toledo, or Made in Mansfield, or Findlay Rocks.

So, we thought, how hard could [designing apparel] be? We’re connected with tons of great graphic designers who work as contractors designing ads for us, we have some business experience, it fits our mission, and it’s a relatively low cost of entry. Setting up an online storefront is ridiculously easy and cost-competitive. We thought, what the hell, let’s try it. The worst thing that can happen is that we make this stuff and everyone hates it. Then we can give it away at high school football games by throwing it into the stands, kill the website, and move on.

So we did it. We started the project in October 2014. We launched the website, with product, on December 1, 2014. We sold out of nearly the entire collection by the end of December, and generated about $6,000 in revenue in a month. We pretty nearly broke even at that point.

The region was right for it. They loved it. Every time I wear a Made in the 419 T-shirt, I get comments on it. We give the t-shirts out to staff and encourage them to give them away as Christmas presents. They’re great promotional items for advertisers. And it created a brand that was associated with Richland Source. I was never going to be able to sell Richland Source t-shirts, but I can sell Made in the 419 T-shirts. If you can do community pride in a cool way that is well designed and on high-quality apparel, people like it.

We’ve started to develop wholesale relationships with select coffee shops and boutiques in town, and that has helped us with local distribution.

We’re in the planning stages of building a membership program now, but we didn’t want it to be subtractive — we didn’t want to take away content or value from someone if they didn’t pay us. That didn’t feel like us. What we’re working on, instead, is more of a nonprofit model, where the membership program is additive. We’re reaching out to initial partners to create benefits and a value proposition program where individuals can purchase a membership to Richland Source, probably in two or three tiers. None of those tiers includes a paywall.

We’re thinking of an electronic or physical card, like a punch card or an app, that gives the cardholder discounts or special benefits at area advertisers. We’d start with our current advertising ecosystem to build out what that benefit package would be.

We’re starting to hold events now, and they’re another potential revenue-generating stream. Our first major event is planned for October; we’re hosting a mayoral debate along with four other area partners. We’re having it at the local theater in town, and a Richland Source member might get preferred seating at the debate, or we might have a member reception. We’ve brainstormed with editorial about a guest column. Or someone from our team might speak at a Richland Source member’s organization, or a charity they’re involved in.

Another idea we’re kicking around is that, at a certain tier, a member would be able to designate a charity to receive a credit for display advertising on Richland Source. Let’s say Joseph Lichterman became a member at Richland Source at the highest level, $200 per year. You’d be able to designate, from a dropdown list, a local or national 501(c)3 of your choice, and then we would create a credit account for that charity in the amount of, say, $100 for display advertising. That credit amount would continue to go up for every single member who designates that charity for advertising.

We’re going slowly on this. We want to be mindful. We want to let people to participate at a level where they really feel as if they’re getting more than they put in.