Half the population of Syria has been displaced. Hundreds of thousands have died in the conflict and millions are fleeing. For those who remain in the country, critical infrastructure is unstable and might be under the control of warring factions at a given moment. The Internet is constantly interrupted. Cell phone coverage can be spotty.

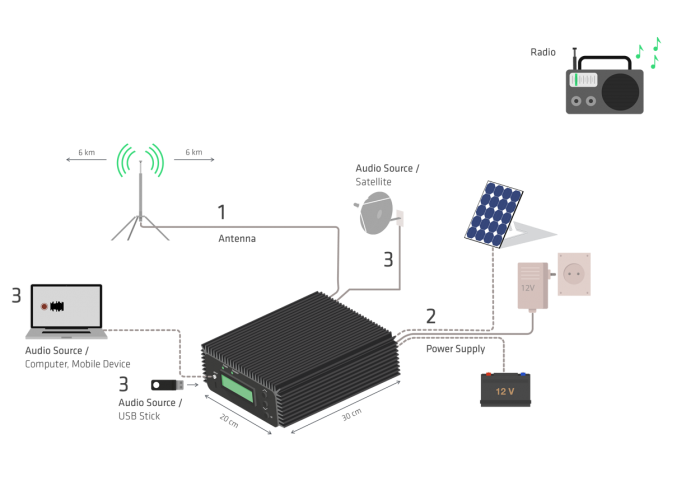

Enter Pocket FM, a portable FM transmitter the size of a shoebox that starts working as soon as it’s connected to a small antenna, a power source, and an audio signal. Pocket FM resembles a radio receiver more than a transmitter, and a single device can air radio programs over a radius of about six kilometers. At its core is Raspberry Pi, an affordable mini computer that can easily be further developed and modified with different features for different scenarios.

Pocket FM was developed by the Berlin-based nonprofit Media in Cooperation and Transition in collaboration with design firm IXDS. MiCT, which focuses on media development in crisis regions and doesn’t usually create hardware, had been working to set up an independent Syrian radio network known as the Syrian Radio Network, or Syrnet, with support from the German Federal Foreign Office. The network combines programming from stations within and outside the country and circulates local reporting from those stations more widely.

As part of its Syrnet project, MiCT helped design the modular, portable Pocket FM to spread the FM signal to areas where it may not be possible to set up a large FM transmitter. (Syrnet shows can also be downloaded from the Internet, but small Pocket FM transmitters set up in the country broadcast the programs locally.)

“The challenge in Syria is that it can be scary, in some areas, to set up big FM transmitters, because they are easy to detect, easy to destroy, and expensive to run,” said Klaas Glenewinkel, MiCT’s co-founder and director. “We had the idea of bringing in many small ones and creating a mesh of radio transmitters so people can access local information where TV and other means have failed.”

Big radio transmitters, Glenewinkel said, were sometimes stolen by people who then demanded money for their return, or could be co-opted to broadcast certain messages. But a decentralized network of hard-to-spot transmitters circumvents those obstacles and is simpler to set up in remote areas. Pocket can also find new frequencies to broadcast on if one is jammed, and can even send out quick text messages to listeners using the RDS protocol.

“When there is no existing infrastructure that is stable for any kind of media, we thought, let’s come back to good old radio,” Glenewinkel said. “But FM transmitters have not really developed in past 20 or 30 years. So we thought, OK, let’s go back to this and think about what FM transmitters of the future could look like.”

The team that participated in the initial creation of Pocket involved not only staff from MiCT and IXDS but also software developers, people from NGOs, radio engineers, and logistical experts who helped coordinate transport (both legal and illegal) of various pieces of Pocket FM equipment to difficult-to-reach areas. “This is not just an app that you can download from the store. It’s still a physical device. If you want to bring equipment from Germany to Syria, into Aleppo, you need a lot of coordination,” Glenewinkel said.

Critical to the process were Syrian activists and journalists intimately aware of the on-the-ground situation in their home countries. Among those who fled Syria and now reside in Germany, Glenewinkel said, were many qualified journalists with connections to peers and colleagues still in Syria.

Syria isn’t the only country where MiCT is using radio systems to spread information. The first iteration of Pocket FM is also beta-testing in Sierra Leone in collaboration with the Freetown-based Culture Radio, in an effort to target communities that haven’t had access to any media campaigns around the prevention of the spread of Ebola. Various villages across all the country’s provinces received FM transmitters, as well as receivers, to broadcast education and awareness-related content tailored to that region.

MiCT also has initiatives ongoing in other countries such as Yemen and Tanzania. (At the moment MiCT has distributed 23 units of the first prototype of Pocket FM inside Syria, one in Yemen, two in Tanzania, and eight in Sierra Leone.)

The team dedicated to Pocket FM has grown quite a bit since it was first piloted, and is hurrying to finish the new version by the end of the year. (A Slovenian company is manufacturing the hardware.) Developers are working to add features that will bolster security for the journalists and activists who might use the device, including the ability for someone running the transmitter to turn it off remotely via a mobile phone. Other new features include a built-in solar panel, GPS, and Internet connectivity. The more powerful version of Pocket FM will cost about $2,000 (USD).

Glenewinkel said that the team has been getting a lot of requests from people who want to use the device, and he hopes their affordable new version will be on the market soon. When that time comes, the team will be have to be careful about who gets a hold of it.

“Right now the twenty to thirty pieces we have are within our control,” Glenewinkel said. “Once we advertise it and sell it, we will need to have some kind of serious vetting process to find out whether this person who called is actually who they say they are.”