There’s a kind of experience that’s particular to Twitter: A casual user, curious about the latest bit of Trump news, checks the service to see what people who have experience with these issues are saying in real-time, glimpsing a tweetstorm punctuated by egg-avatared trolls, irrelevant replies, and maybe a few good criticisms. It can be overwhelming. (Even in a crazy election year, Twitter added no monthly active users in the U.S.)

Sidewire — proclaiming to be “where experts chat in public” — wants to squeeze out the trolling and abuse prevalent on platforms like Twitter and clear a space for calm discussion free of social media “noise.” It limits chat participants on the platform to vetted “newsmakers” and trims conversation topics to just a handful of the most consequential or debateworthy news events. Launched in September 2015, it now hosts around 800 “verified experts,” around a third of whom are journalists, in its politics vertical, and around 100 in its newer tech vertical.

“There’s just not a lot of junk or noise. No one’s trolling, no one’s beating up on each other. There’s a really different kind of discourse going on here than anywhere else on the Internet,” said Jon Allen, Sidewire’s head of community and content. “We’ve got people on the platform who are as far right and as far left as it gets in modern politics. But we’ve cultivated a community that is, by design, respectful and informed above all else.”

Sidewire invites “newsmakers” to the platform, and they can in turn invite others (if you qualify as an “expert” of some sort, you can apply to join here).

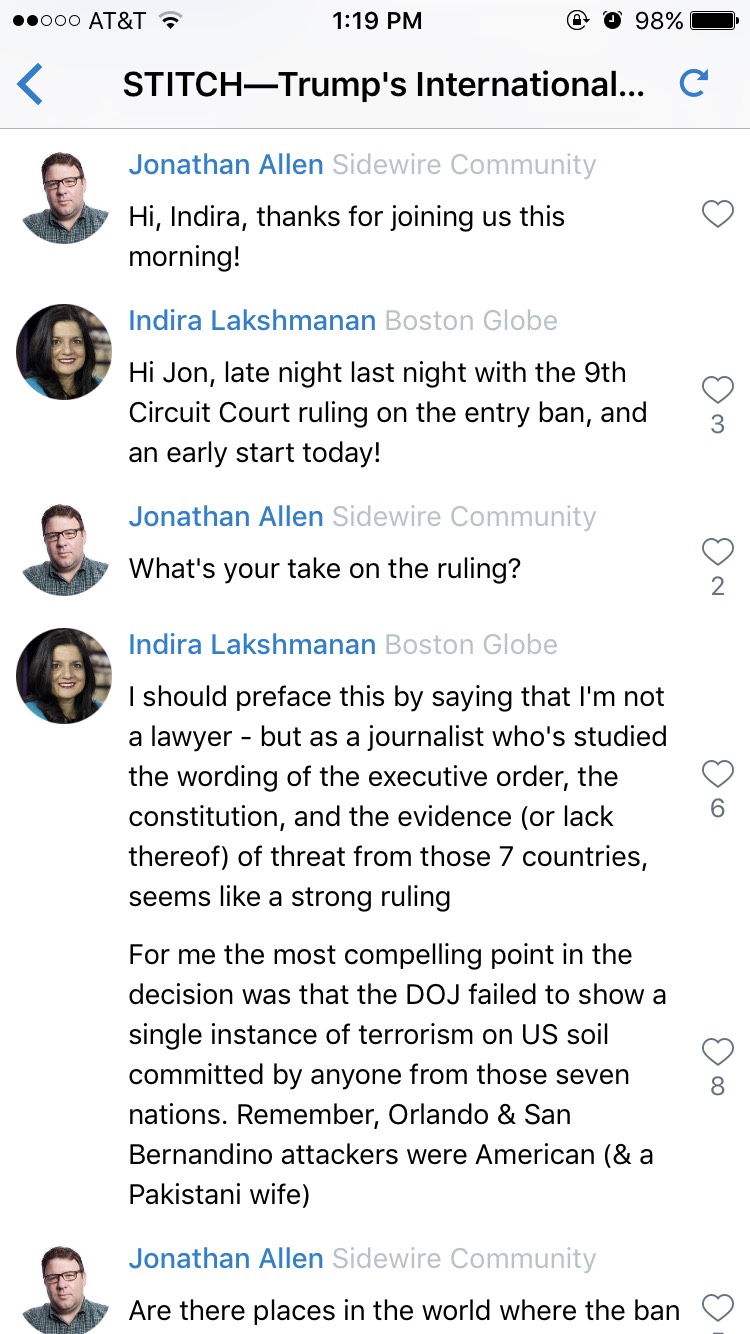

What’s the discourse like? Consider this recent example of a very controversial topic:

The Conservative Political Action Conference had rescinded a speaking invitation to right-wing troll and Breitbart News editor Milo Yiannopoulos after a video surfaced of Yiannopoulos defending sexual relationships between “13-year-olds” and “older men.” (Yiannopoulos ultimately apologized and stepped down from Breitbart. He said he still plans to launch an “independent media venture.”)

The Conservative Political Action Conference had rescinded a speaking invitation to right-wing troll and Breitbart News editor Milo Yiannopoulos after a video surfaced of Yiannopoulos defending sexual relationships between “13-year-olds” and “older men.” (Yiannopoulos ultimately apologized and stepped down from Breitbart. He said he still plans to launch an “independent media venture.”)

“As a Republican…I view Yiannopoulos as a comic book character,” the host of the online radio show Backroom Politics wrote on Sidewire. “I am still amazed that he has alt right fans!”

“Maybe it’s because the president defends him personally,” replied the former director of international economic affairs under the Obama administration.

“Can I play devil’s advocate for a moment: He’s a performance artist and being disinvited plays into his ‘art,'” Vice News’ Washington bureau chief Shawna Thomas offered.

“Can I play devil’s advocate for a moment: He’s a performance artist and being disinvited plays into his ‘art,'” Vice News’ Washington bureau chief Shawna Thomas offered.

Sidewire staffers curate chats by posting news stories and ping relevant people on the platform to come discuss them. Those approved to use Sidewire can also open up their own chats around a news topic, inviting other people who they think would be insightful participants. The relative civility on the platform is due in part to Sidewire’s focus on only the top couple of political or tech stories in the news cycle each day, despite the current administration’s turbulent, story-dense first weeks in office. It’s also due to the fact that readers can’t do much to weigh in except “like” the statements made by newsmakers.

Vice’s Thomas, who was invited to Sidewire last year while she was at NBC News’s Meet the Press, said that the platform hasn’t exactly been part of her “regular social media diet,” but she’s found push alerts from the app about new chats and Q&As useful as a way of finding new sources for her own work.

“I’m interested to see what conversations are going on, if only to get ideas about people to talk to, [like] former administration officials about policy changes we’ve seen. Jon Allen is really good at getting these people together to have discussions,” Thomas said. “If another expert is talking, it could be a good way for me to get something answered, or to explore another point of view.” (She’s not as interested in the other journalists on the platform: “I see what journalists say on Twitter all the time.”)

Only a few chats take place on any given day; some days there’s just one. Sidewire staffers highlight the best insights from within each day’s chats (the biggest day so far was November 8, Election Day, with 14 total chats). In anticipation of a big policy decision or a scheduled announcement, Sidewire might line up a set of newsmakers and schedule a chat in advance.

In February, when news broke that the Trump administration was relaxing certain sanctions on Russia, “the Twitter universe went nuts with the idea that Trump was bending over backward for Russia,” Allen said. “We posted the story to Sidewire and invited newsmakers to weigh in. Within a few minutes, we were determining the substance and significance of the policy changes, the political ramifications of it, and had everyone from a former State Department spokesperson to reporters from Bloomberg and Vice weighing in on what they were hearing.”

In February, when news broke that the Trump administration was relaxing certain sanctions on Russia, “the Twitter universe went nuts with the idea that Trump was bending over backward for Russia,” Allen said. “We posted the story to Sidewire and invited newsmakers to weigh in. Within a few minutes, we were determining the substance and significance of the policy changes, the political ramifications of it, and had everyone from a former State Department spokesperson to reporters from Bloomberg and Vice weighing in on what they were hearing.”

Sidewire recently started offering the option of “shielded” posts that hide the identity of the newsmaker weighing in. (So far, this hasn’t resulted in any increased trolling on the platform.) Its next area of focus, said Sidewire CEO Andy Bromberg, will include ways to let newsmakers get feedback from readers within Sidewire itself, while still keeping trolls at bay.

On Twitter and even Facebook, the news and takes and jokes (as well as the terrible abuse) come at you fast and furious, giving users an infinite firehose of stuff to consume. But is there enough content to read on Sidewire to keep people coming back? “We care more about being a place where the content’s created than where it’s consumed,” Bromberg said. Sidewire chats can be shared on Twitter and Facebook, embedded into other sites, and followed on Facebook Messenger.

Sidewire is running on $4.85 million in seed funding and plans to raise more money down the line. (Possible revenue model, still a ways away, might involve ads or white-label versions of Sidewire for other news organizations.)

Talkshow, another service focused on public discussion, shut down six months after launch. And Twitter Moments, the platform’s attempt to offer easier-to-understand slideshows around notable events, was demoted to a broader “explore” tab in the app in January, and often fails to capture well the essence of an event (see: its confusing moment from this year’s Oscars). Will Sidewire succeed where similar efforts have stumbled? Bromberg declined to disclose how many users (i.e., non-newsmakers) Sidewire has, but said most of them are in D.C., New York, and San Francisco, with a fairly evenly split between men and women. There’s also “an amazing community in Iowa,” where Sidewire officially launched its app back in 2015. And there are “strong coalitions of local newsmakers in a lot of the early primary states,” Bromberg said. Sidewire is also looking to add verticals in sports and entertainment.

Bromberg declined to disclose how many users (i.e., non-newsmakers) Sidewire has, but said most of them are in D.C., New York, and San Francisco, with a fairly evenly split between men and women. There’s also “an amazing community in Iowa,” where Sidewire officially launched its app back in 2015. And there are “strong coalitions of local newsmakers in a lot of the early primary states,” Bromberg said. Sidewire is also looking to add verticals in sports and entertainment.

As criticism of journalistic navel-gazing mounts and President Trump positions many news organizations as enemies, I asked Bromberg if a highly vetted discussion app featuring only the “top experts” might not appeal to a particularly broad audience — especially if the audience is purposefully held at arm’s length.

“Certainly, Sidewire right now is not a fit for everyone to read,” Bromberg said. “But if you put those ‘elites’ in dialogue with each other, and all of a sudden their ideas are being questioned by the other side, it changes the texture of the dialogue a lot.”

“The normal person might struggle with all the long thinkpieces being published now,” he added. “They are hard to sit and read; they carry so much weight. We bring a level of simplicity and level of readability to what the ‘elites’ have to say, which can often be tremendously valuable. It can open your eyes to this idea that different perspectives exist, without needing to seek out dueling essays on something.”