Even if they haven’t changed the world in the way some hyped, chatbots have become a compelling way for news organizations to experiment with telling familiar stories in a new format. Some big challenges stand in the way of widespread adoption, though. One is acclimating users to the format; another is winning over reporters.

The BBC News Labs and the BBC Visual Journalism team are trying to solve both issues with a single solution: a custom bot-builder application designed to make it as easy as possible for reporters to build chatbots and insert them into their stories. In a few minutes, a BBC reporter can input the text of an article, define the questions users can click, and publish the bot, which can then be reused and added to any other relevant article. BBC reporters can even repurpose existing Q&A explainers into bot-based conversations.

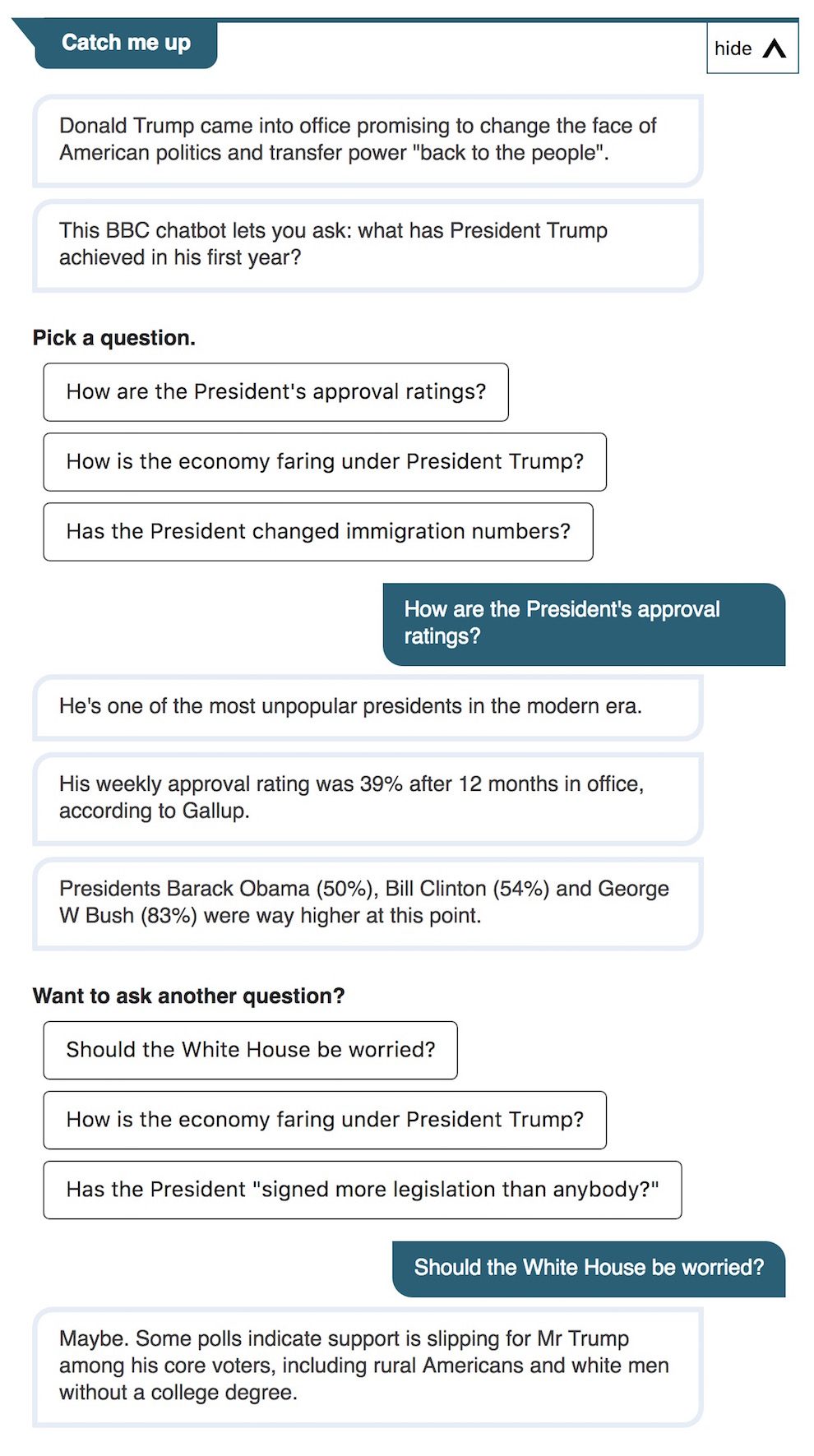

So, on this story about a typo on State of the “Uniom” tickets, a “Catch me up” module says: “Donald Trump came into office promising to change the face of American politics and transfer power ‘back to the people.’ This BBC chatbot lets you ask: what has President Trump achieved in his first year?” Three potential questions are offered. (How are the President’s approval ratings? How is the economy faring under President Trump? And has the President changed immigration numbers?) Pick one and a chat interface expands with answers. (“He’s one of the most unpopular presidents in the modern era.”) With each answer, one or more new questions pop up as options; the Trump chatbot contains more than a dozen in all.)

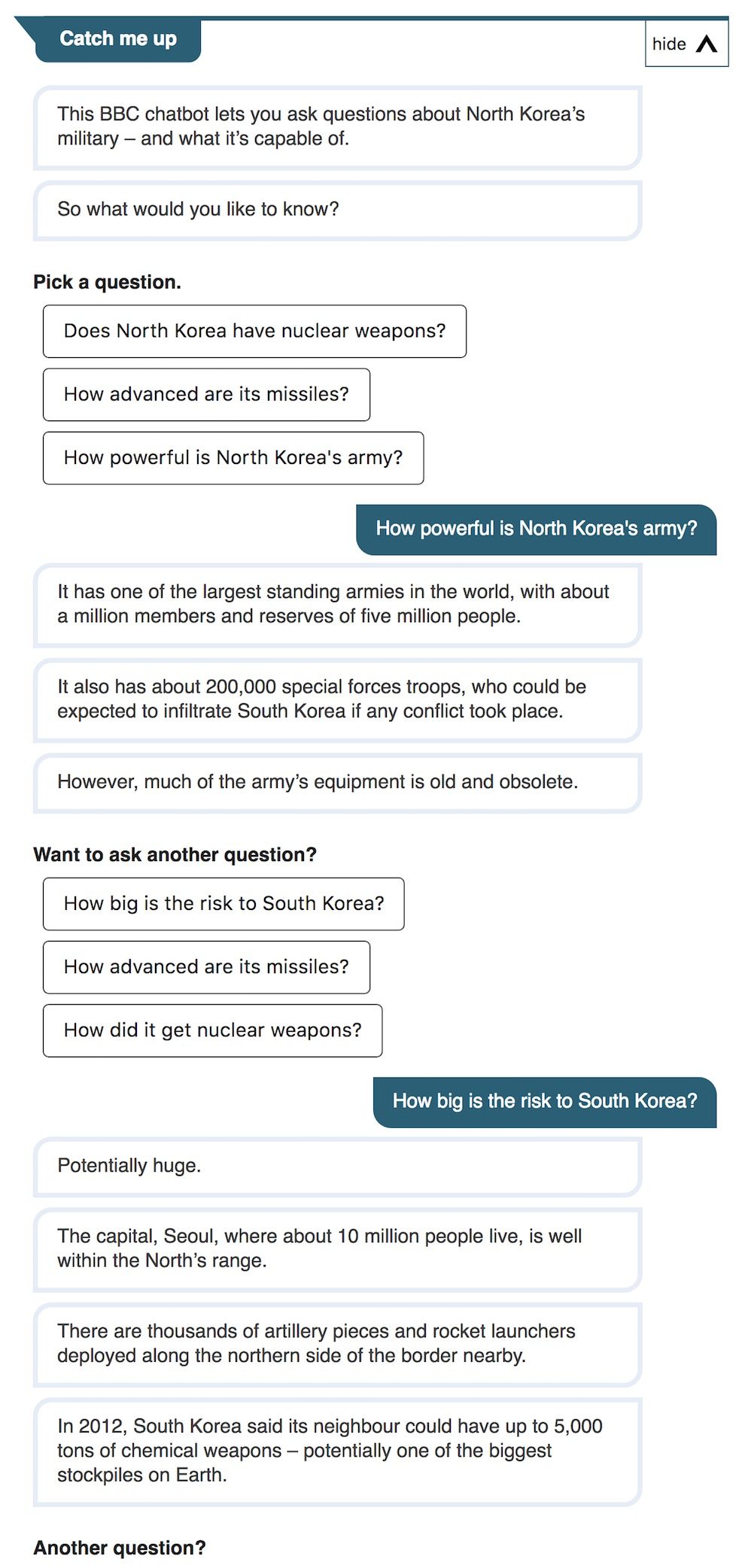

For the BBC, bots represent a new way to reach and inform readers who are not deeply engaged in complicated news stories, said Heinrich. One recent bot set out to help users understand how the sharp rise in personal lending might affect them. BBC has also used the tech to help readers catch up on the situation in North Korea and understand the latest flu outbreak. And these bots can all be reused in any piece that reporters think will benefit from deeper background information; the Trump’s-first-year chatbot had run in at least 10 BBC stories.

“These topics, like Brexit, are complicated ones that people often struggle with, and the bots are designed to help demystify them,” said Heinrich. “Readers can be a bit younger, or come into the story midway. They may not know who the important people are, or what the story is. Journalists are much more involved in these stories day-to-day and your average 16 year old won’t be as familiar.”

The BBC News Labs and the BBC Visual Journalism team have tweaked and experimented with various parts of the bot project, such as the placement of the bot module on pages, bot design, and whether the bot modules should appear on pages by default, versus forcing users to click a tab before using them. The teams also want to determine how effective the bots within breaking news stories, or even in coverage of entertainment stories such as the Oscars. Another variation on the current bot modules in development now is a timeline feature, which will let users catch up on key events that lead to the current story they’re reading about. The teams are also exploring ways to track where people stop interacting with a bot — particularly a verbose one covering a complex topic — which will let them ping users down the line if the story changes.

A few lessons have become clear already, however. For one, the BBC has found that every bot tends to attract a small, but highly engaged subset of users who spend a lot of time interacting with the modules. In other words, certain topics that the bots cover might not be relevant to most people, but those who are interested in their topics “will devour anything that explains them,” said Heinrich. “It’s that audience that bots are for.”

Ultimately, Heinrich said that it’s important for news organizations to be realistic about what chatbots can accomplish. “They’re not applicable to every story and there are going to definitely be stories where it’s not worth the effort of building them,” Heinrich said. “But if you have a really complicated, long piece and you want people to grasp the basics very quickly, they’re very good. Our goal isn’t to prove to readers that the chatbot is the wave of the future for every form of journalism.”