When I walked into a public event at WGBH’s headquarters in Boston last Thursday, I was struck by how the race against time was so…silent. About a dozen WGBH volunteers and staff members had assembled with laptops and headphones, playing with and testing some tools developed by WGBH’s digital team and archivists. (The AAPB is a collaboration between WGBH and the Library of Congress, and this project is funded by the Institute for Museum and Library Services.) Staying silent was true to the goal of this event, the station’s first “transcript-a-thon”: enlisting the public to re-evaluate computer-generated transcripts and related metadata on recordings from the station’s 30-year-old working archive.

The name of the event might not be the most glamorous (especially when transcription is frequently the bane of journalists’ existence), but with around 1,000 players in just under a year since the tool’s launch, the team wants to see if the game experience they’ve built can catch on with the public.

“This is a game we want people to enjoy playing, but the goal is to correct the transcripts and get them out,” said Casey Davis Kaufman, WGBH’s media library associate director and project manager of the AAPB. “We had to think about the best way to develop the pipeline and workflow.”

In 2013, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting provided funding for more than 100 public radio stations across the country to take stock of and later digitize their archival closets. WGBH and the Library of Congress became the permanent home for more than 40,000 hours of programming, or about 68,000 programs and pieces of original material and growing, through the AAPB. Every five years, the AAPB aims to keep the archive current by migrating the files to updated formats — so there’s a lot to sort through.The team wondered if a gamified version of transcription checks might entice public radio fans to help assemble the metadata. They decided to start with open-source speech-to-text software developed in conjunction with the Pop-Up Archive, an online platform for transcribing and organizing audio files acquired by Apple last year.

“The machines have done the first pass at trying to turn the recordings into text, but it makes lots of mistakes — lots and lots of mistakes. The machine is pretty good at turning sounds into words, but not so good about grammar and flow and logic,” said Stuart Rubinow, a WGBH volunteer at Thursday’s event. Working on these transcripts in a group “is more fun, and I’m not sure why,” he said. “There’s relatively little interaction between people, because we’re all working with our own files on the machines. But it’s nice to do here.”

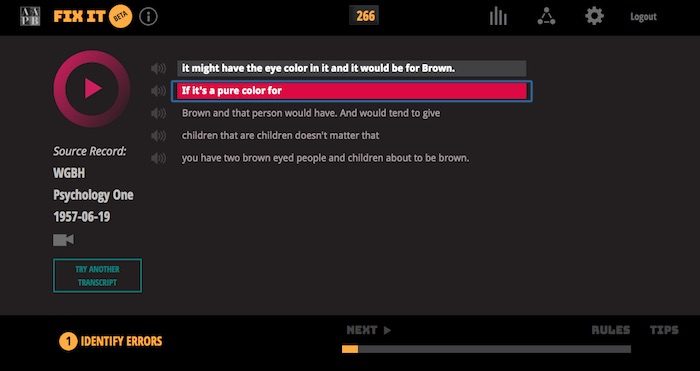

WGBH created three tools in-house: Fix It, Fix It Plus, and Roll the Credits. Fix It encourages players to score points by identifying errors, suggesting corrections, and approving other players’ suggestions. “You’re racking up points — there’s a leaderboard where you can see how much you accomplish in comparison to other players — but in general, I think the primary motivation for people contributing to these type of efforts is because they have time and want to give back to a worthy cause,” Kaufman said.Anyone can access Fix It, to work on files ranging from the scientific arguments for nature and nurture to Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, covering the digitized inventory of stations nationwide. Users can choose their preferences for the first part of the game, where you listen closely to recordings to identify errors in the transcript; the recordings are a grab bag in the second round of suggesting corrections, and in the final component of confirming other players’ suggestions. The random decades-old recordings are spliced into manageable five-minute segments in Fix It, providing just enough incentive to play a few rounds. A teacher in Seattle, for example, is having her high school students compete in Fix It as part of their homework assignments, Kaufman said.

The game is surprisingly fun, and the osmosis-like learning process adds to its charm. In a few rounds last week, I listened to a Harvard professor lecture on biological inheritance in 1957, tried (and failed) to decipher lyrics of a rock song, and reviewed others’ suggestions for edits on Mississippi Public Broadcasting’s Elvis 25th-anniversary-of-his-death special. It’s the kind of random stuff — source material from back in time — that I never would have listened to on my own.

The other parts in the AAPB’s transcript-a-thon toolkit, Fix It Plus and Roll the Credits, are more tools than games. Fix It Plus was showcased for the first time at last week’s WGBH event; it removes the segmented three steps from Fix It, so you can more satisfyingly follow through on a transcript from beginning to end (though the completed transcript is always still sent to another person for independent verification). It was adapted from a transcript editor framework set up by the New York Public Library.

Roll the Credits, meanwhile, delves into the visual archives by taking stills of the first and last two minutes of a program to capture the metadata for those items. Roll the Credits works with a platform called Zooniverse to upload the images and asks players to record the information from the credits, such as the copyright year and the names of people who contributed to a segment.

“The tools we’ve developed were all grant-funded, and our grant is still underway. This has been an opportunity for people to physically come in so we can we can test the tools,” Kaufman said. The small group at the event was divided up into smaller groups to hone in on a tool for 45 minutes before taking a break to debrief and share feedback, and then continue on.

WGBH won’t be the only station hosting transcript-a-thons; other stations have expressed interest in getting their audiences to play along as well. “This is also a chance to meet with archivists and get to learn more about the artifiacts from the vault,” Kaufman said. “[Participants] get to learn not just about the transcripts they’re working on, but about the work we do to preserve WGBH’s history.”