News is more unevenly distributed in the UK than income is, according to new research from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Antonis Kalogeropoulos and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen found that poorer people consume less news than wealthier people and that the difference is particularly pronounced online, where poorer people are less likely to go directly to news sites for content.

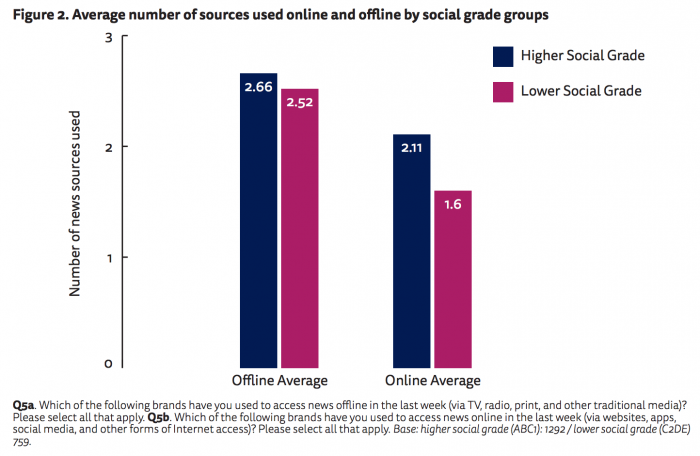

“Whereas higher social grade individuals and lower social grade individuals use the same number of sources offline on average, lower social grade individuals use significantly fewer online sources on average,” the authors write.This is in the United Kingdom, land of the great equalizer the BBC, which reaches a whopping 92 percent of UK adults. There is no media company in the U.S. that comes close. Income inequality is also higher in the United States than in the United Kingdom. In other words: This study focuses on the UK but the problem is likely the same or worse in the U.S.

We find greater social inequality in online than offline news consumption. Whereas higher (ABC1) and lower (C2DE) social grade individuals in the UK use same number of sources offline on average, lower social grade individuals use significantly fewer online sources on average 2/5 pic.twitter.com/toAmmmkhJd

— Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (@rasmus_kleis) October 18, 2018

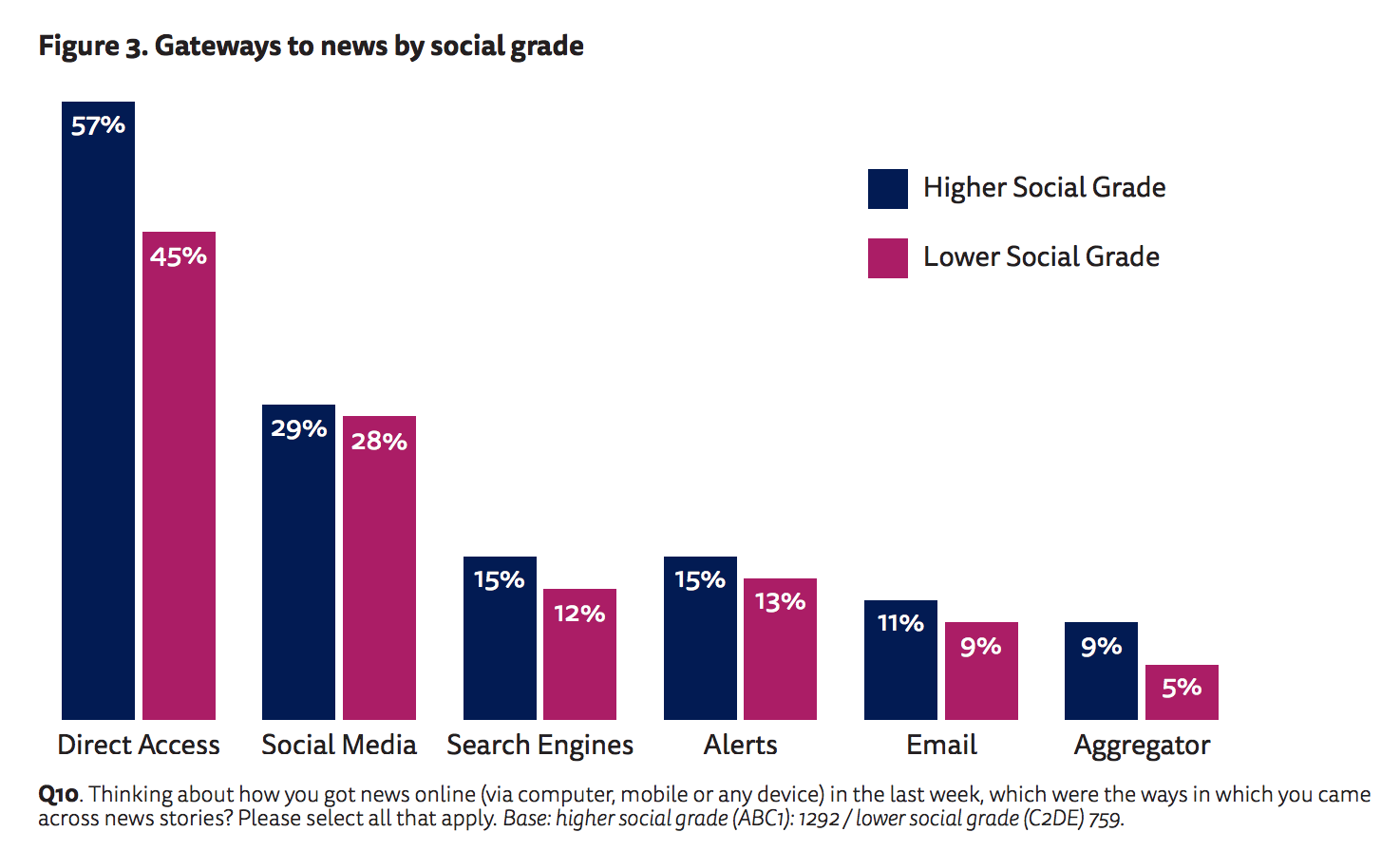

One big difference in income groups in the U.K. is the types of news that they access online. “Lower social grade individuals are significantly less likely to go direct to news providers, whereas lower and higher social grade individuals are equally likely to rely on distributed forms of discovery (relying on social media, search engines, and the like),” the authors write.

There was also “no online news brand among the 32 included in the survey that had significantly more users from lower social grades.”

“Swapping mass for niche media means there are plenty of top-notch news outlets targeting well-off, highly educated people, or demographically appealing young people,” our Josh Benton wrote last year, “but fewer targeting everybody else.”