On January 11, in the midst of a deepening crisis of public trust for the company, Facebook’s Adam Mosseri (now head of Instagram), wrote that the company would be changing how the News Feed worked. It would now de-prioritize publishers’ content in favor of posts from users’ friends.

Publishers were understandably worried. Digiday reported in mid February that “Chartbeat data showed Facebook traffic to publishers declined 6 percent since the beginning of January.” By the end of the month, LittleThings, a publication focused on “a mix of feel-good news and service content” for women, shut down, citing the algorithm change as the key reason. LittleThings’ CEO said its organic (non-paid) traffic from Facebook dropped 75 percent, noting that “no previous algorithm update ever came close to this level of decimation.” In June, Slate summed up the impact of these changes as “The Great Facebook Crash,” showing the remarkable decline in Facebook referrals to its own website. The story noted that “for every five people that Facebook used to send to Slate about a year ago, it now sends less than one.”Just last week, Axios noted that, according to Chartbeat, “a user is now more likely to find your content through your mobile website or app than from Facebook” because Facebook referrals were down “nearly 40 percent”.

At the Shorenstein Center, part of our mission is to bridge the gap between academics and journalists. To that end, we’re currently working with a group of nonprofit publishers through the Single Subject News Project, helping them to grow and engage their audiences and learning best practices in the process. As a part of that collaboration, we took a look at what has happened to Facebook referrals to this group. We suspected that their Facebook referral traffic would be qualitatively different than that of bigger commercial publications.

That appears to be true. We looked at eight nonprofits that are a part of our ongoing research. We selected three investigative news organizations — the Center for Public Integrity, ProPublica, and Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting — and five that cover a single subject (Chalkbeat, The Hechinger Report, The Marshall Project, The Trace, and The War Horse). We used two metrics, sessions and users, and looked at the three months before and after the news feed changes. Together, those measures show both the count of individuals and the average depth of their interaction.

We found that most of the organizations in our cohort did see a reduction of traffic from Facebook, but on a much smaller scale than what some large commercial players like Slate have reported. We also found that traffic overall was actually up across both our metrics.

Of the eight publishers, three saw significant (greater than 20 percent) declines in Facebook referrals. Two were down slightly; two were up slightly. And one saw significant gains, up more than 40 percent in both users and sessions.

Percentage change in users and sessions referred from Facebook in the three months before and after the Facebook News Feed algorithm change at eight (anonymized) nonprofit news organizations.

Percentage change in users and sessions in the three months before and after the Facebook News Feed algorithm change at eight (anonymized) nonprofit news organizations.

Without being overly Pollyanna-ish, there’s a surprisingly positive result for these nonprofit publishers: Regardless of what Facebook does — something no news organization could ever hope to control — there are still paths to growth in audience. Put another way, there are other acquisition strategies that can take the place of Facebook.

While we hoped there would be trends in those strategies, the results, shown in the table below, were not as enlightening as we had hoped. While these groupings may be a useful management tool — consistent growth in Direct and Email traffic could be expected almost regardless of the vagaries of a platform’s algorithmic change du jour — in the case of our cohort, there was little consistency.

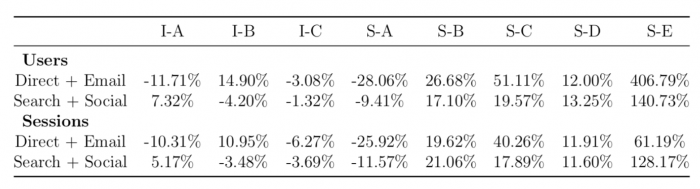

Percentage change in the three months pre- and post-News Feed change, combining the Google Analytics channels more directly controlled by publishers (Direct and Email) and those controlled by technology platforms (Search and Social).

While the analytics data alone can’t tell us why these non-profits didn’t see drops in Facebook referrals, if one takes Facebook’s change announcement at face value, it could be that the company never intended to impact this group of publishers. If, for example, the primary way that an organization’s links are shared on Facebook is by users instead of by the organization’s own Page, its standing in the News Feed could improve as a result of this change.

More bluntly, it could be that these organizations were never equipped to game the system in the way that larger publishers could. Indeed, in the same piece where Slate’s technology columnist lamented the decline in Facebook traffic, Will Oremus explained how the company actively bought traffic using various intermediaries, all of which contributed to Facebook referrals. In the case of this nonprofit cohort, some had attempted to buy traffic, but only on a small scale.

It would also be useful to conduct preliminary research on the methods that small news organizations could use to conduct these experiments (on how to best use the Facebook News Feed for growing traffic) on their own. One could imagine a repository of methods that helps publications learn which kinds of advertising A/B tests to run and what to learn from them.

Bottom line: The decline in referrals to publishers from Facebook is not universal, and in the face of those declines, other sources of traffic are more important than ever.

Andrew Gruen is a research fellow at the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy. With Aisha Townes, a data science consultant at Shorenstein, he cowrote “Facebook Friends? The Impact of Facebook’s News Feed Algorithm Changes on Nonprofit Publishers.”