This week, the BBC devoted attention to a series on the spread of false information:

The BBC is launching a series today on disinformation and fake news, with documentaries, reports and features on TV, radio and online. There are conferences in Delhi and Nairobi, and new research from India and Africa into why people spread fake news. https://t.co/YaWajNNDWC

— BBC News (World) (@BBCWorld) November 12, 2018

As part of its reporting, the BBC researched how ordinary citizens in India, Kenya, and Nigeria interact with fake news: “Participants gave the BBC extensive access to their phones over a seven-day period, allowing the researchers to examine the kinds of material they shared, whom they shared it with and how often.”

This is really extensive research, including in-depth in-person interviews in multiple native languages across cities and regions plus the analysis of news in English and local languages across social media. The reports are long and worth reading in full, but here are some of the findings from the India report, which was written by Santanu Chakrabarti, head of the BBC World Service audiences research team, with senior researchers Lucile Stengel and Sapna Solanki. (The Kenya and Nigeria report is here.)

The boundaries between different types of news (information, analysis, opinion) has collapsed in India. “With the definition of news becoming expansive and all encompassing, we find that anything of importance to the citizen is now considered ‘news.'”

Data costs and the costs of smartphones have dropped significantly in the country, and as a result people report getting notifications as often as every 2 to 4 minutes:

We find our respondents inundated with messages on WhatsApp and Facebook. There is a near constant flurry of notifications and forwards throughout the day on their phones — encompassing from news organizations updates to a mindboggling variety of social messages (for example, “inspiring quotes” and “good morning” forwards, the latter of which seems to be a peculiarly Indian phenomenon, even the subject of discussion in the international media).

News providers — and there are tens of thousands of them in India — do not make it any easier, by sending regular, even incessant, notifications to phones.

The researchers found that the respondents’ default behavior was to keep notifications on and “we believe this behavior is quite widespread, for many respondents, when asked how they come to know about a news event, say that it’s ‘because of notifications’…In India, citizens actively seem to be privileging breadth of information over depth.” In a striking difference from America, the researches found that “Indians at this moment are not themselves articulating any kind of anxiety about dealing with the flood of information in their phones. If anything, they only see the positives of social media.”

This doesn’t mean that people haven’t found ways of dealing with the information deluge — they have. They often don’t open notifications at all, or they screen them and only open some from certain senders. One 27-year-old Mumbai man said: “I trust anything my Mamaji sends, he knows a lot about the world. There are my other uncles who stay in our hometown, I instantly mistrust anything they send. I don’t even open most of their forwards.”

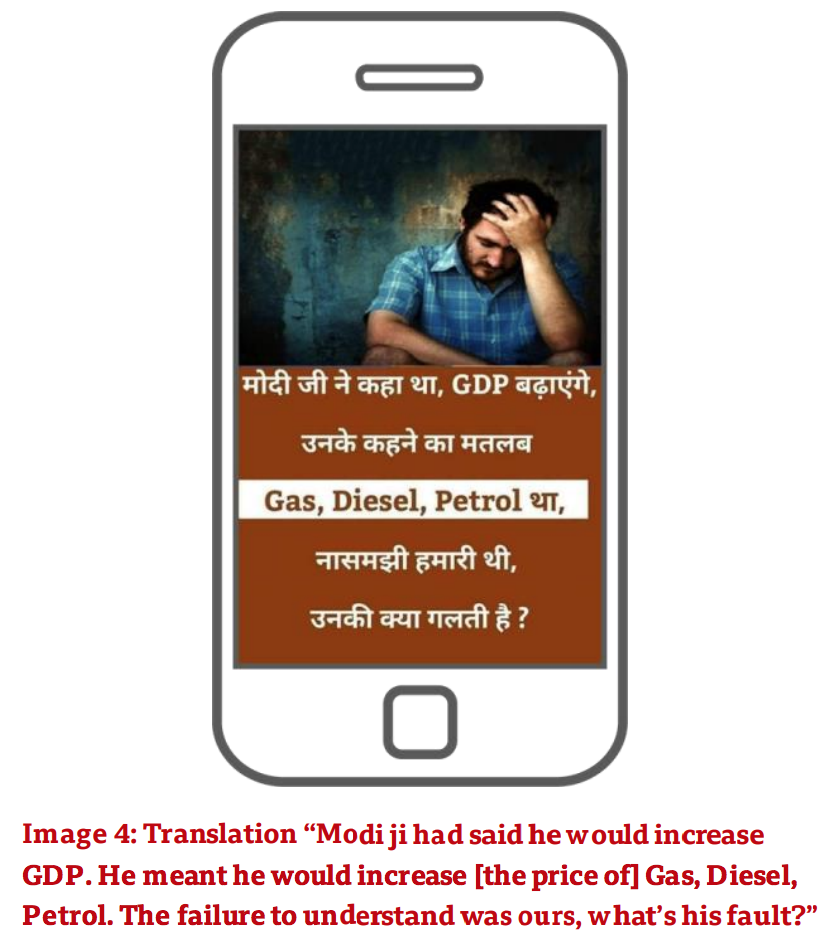

Images are “overwhelmingly preferred for consumption or to engage with.” This, the researchers write, is one of their most important findings about fake news in India:

The canonical example of fake news, for example, the story about the Pope endorsing Donald Trump, created by Macedonian teenagers, and circulating all over social media, does not seem to be that prevalent in WhatsApp feeds in India. To be clearer, stories as a collection of words on a website, circulated in the form of the url, do not seem to be the most prevalent means of sharing information (and disinformation). The form of information that is consumed or engaged with more, is visual information, sometimes layered with a minimum amount of text.

Sourcing of the actual information shared is usually totally absent; rather, “the credibility of the sender is what gives legitimacy to the message. The original source, if at all present in the message itself, is often ignored or unnoticed in Facebook, or completely absent in WhatsApp.”

People are very careful about which messages they share in which WhatsApp groups. “Every group in WhatsApp has something that bonds the groups together — and makes it behave like a group,” the researchers write. WhatsApp group sharing is “very targeted” and “people are “acutely conscious of which messages belong in which groups.”

This suggests that the chances of a fake news message spreading on a nationwide scale on WhatsApp might actually be quite limited. The defining feature of WhatsApp groups in India might then not be its reach or scale or speed of transmission of messages, but the fact that it is enabling homophily, or the drawing together of people in tight networks of like-mindedness.

But because of this tightness, then, we suggest that it is possible to use WhatsApp to mobilize. This starts to explain why WhatsApp has seemed quite central to some cases of violence in India. It’s not the speed, or the reach of WhatsApp that has been central to these issues, but the homophily of its groups that has enabled mobilization in the cause of violence.

The “working definition” of fake news in India is “largely limited to scams (all kinds of schemes, offers, and attempted cons)…or messages in the realm of the fantastical, which are just too incredible to believe,” the researchers write; beyond this, “our analysis suggests that people in India are not that concerned about fake news, no matter what they say in quantitative surveys.”

In fact, even knowledge of fake news messages associated with violence is fuzzy at best — and recalled vaguely from media reports rather than from encountering those messages themselves. There is certainly no recognition that it might be getting harder and harder to differentiate between what’s fact and what’s not. And in many ways, there is a level of overestimation of their own abilities to detect fake from fact. As part of the research process, respondents were exposed to a mix of real and fake news messages. And almost no respondent was adequately able to identify the fakes. But one of the more concerning things that we observed happening, though, is that those some looked at legitimate news items or sources and judged them to be fake.

As a result, Facebook and WhatsApp’s attempts to curtail the spread of false information may not work in India at all, the researchers write.

For instance, WhatsApp, under government pressure, added a “Forwarded” tag in India to show that messages might have originally come from an unknown source. But “we observed that citizens for the most part had either not quite noticed the tag or if they had noticed they had misinterpreted what it meant. In what is possibly an isolated case, a respondent even thought that the tag was encouragement to further forward the message on!”

And Facebook warned Indian users not to spread fake news — but since, as noted above, most Indians think of fake news as being money-related scams, “citizens don’t think they themselves have a role to play in this.”