The Boston Globe, the first local newspaper to have more digital subscribers than print, is now investing in more local coverage. In Rhode Island.

After past investments in covering marijuana, the Catholic Church, and health and life sciences (and spinning off the latter two), the Globe’s newest vertical can be found about 50 miles down I-95. Three Providence journalists with more than four decades’ combined experience reporting on Little Rhody news are now officially a remote part of the Globe’s newsroom, writing for residents of the state and not just Bostonians. The Globe is making a bet that the Ocean State is fertile new ground for new subscribers (and they don’t have to worry about printing and distributing newspapers for them).“This is in many ways kind of a digital-age version of what we did many years ago in the suburbs,” Globe editor Brian McGrory said. But now “you don’t have to be directly adjacent to Boston. We saw opportunity in Rhode Island where quite honestly great newspapers like the Providence Journal were seeing significant cuts and that market is particularly engaged in news. We saw the opportunity to create a digital regional enterprise by heading down there and hiring local reporters.”

The reporters are Amanda Milkovits, the Providence Journal’s longtime crime and safety reporter; Ed Fitzpatrick, a recent university spokesperson and former Providence Journal columnist (he and Milkovits started on the same day both at the Journal and now at the Globe); and Dan McGowan from WPRI 12, who spearheads a nearly 7,000-member Facebook group on Rhode Island politics and now the daily Rhode Map newsletter. Their coverage so far has ranged from a Q&A with the state’s senior U.S. senator, in-depth looks at a fancy-pants bridge/community convener that went $20 million over budget, struggles in the Providence public school system, and a profile accompanying breaking news of the local bishop’s homophobic tweet on Sunday. They all seemed terribly thrilled, when I talked to Milkovits and McGowan on Monday’s launch day, to be working for a news outlet that’s actually investing in its journalism.

“The intention of the Globe, and definitely my intention, is to tell more of the [Rhode Island] stories and tell different stories. It’s not to hurt the Journal,” said Milkovits, who spent almost two decades there. “I want the Journal to survive. I love that paper, and I think Rhode Island needs a newspaper. The relationship between the two — there’s room. There’s a lot of room for more journalism in the state.”

Mr. Henry, I know another paper that needs saving HT @IanDon @urbanophile: Boston Mag: Will John Henry Save the Globe http://t.co/9VB12i34Hc

— Amanda Milkovits (@AmandaMilkovits) February 22, 2014

“For the better part of forever, we weren’t focused on Rhode Island because the Journal was so strong. It didn’t leave a lot of room for us,” McGrory said. Now…well, things are different.

Rhode Island isn’t quite close to being a news desert, by UNC’s Penelope Abernathy’s standards. It has six daily newspapers and 20-plus weeklies for a population of 1.1 million. But total circulation dropped by 54 percent between 2004 and 2019, and it doesn’t help that GateHouse’s Providence Journal has consistently — like many other newspapers — dwindled. (GateHouse also owns The Newport Daily News down the road.)GateHouse bought the Journal from Belo in 2014. At the time, its weekday circulation was 74,400. By 2018, that was down to less than 44,000, and another round of layoffs hit in February. What was once a total newsroom of more than 300, back in the 1980s golden age, now has fewer than 15 reporters on staff.

The Boston Globe, while it certainly has its own share of struggles, has seen continued growth in its digital subscription business: As of March 31, it’s now the proud parent of 112,241 digital subs. And those don’t come cheap at $360 per year after initial discounts, a price higher than The New York Times or The Washington Post.

And just as the Times has viewed Australia and Canada as prime targets for expanding its revenue footprint, the Globe — on a smaller scale, obviously — sees Rhode Island as territory to fuel further growth.

“I have so much respect for the folks at the Providence Journal. We’re not coming to work every day thinking that our goal is to squish the paper of record in Rhode Island,” McGowan said. He noted that in a Globe Google form asking Rhode Islanders for their story suggestions that received “hundreds” of responses, one replied “more of everything.” “Rhode Island is very small, but we publish way above our weight when it comes to the news and our on-the-ground journalists…That’s a testament to the other journalists in the market and the work that the three of us have already been doing.”

But the locals won’t go down without a fight: “We’re not about to cede Providence coverage or Rhode Island coverage to anyone,” the Journal’s new publisher, Pete Meyer, said in an April article about the previous publisher’s retirement. WPRI pointed out the story did not directly reference the Globe, though Meyer also said he “would double down to protect our turf” and was “up for a good fight.”

The most important word for the newspaper industry in 2019 has been consolidation, as Ken Doctor has documented here many times. That’s generally been about huge, nation-spanning scale: little chains getting eaten by bigger chains that get merged into enormous chains. Much of that has been about regionalized efficiencies: five or six nearby dailies that can now share a printing press, an ad-sales team, and an executive structure.

But there’s also a more local path: a relatively strong paper deciding to expand into nearby markets where the daily’s ownership might be more focused on cost-cutting than producing a good product.

The Advocate in Baton Rouge is probably the best example of this we’ve seen. Bought by wealthy businessman (and occasional politician) John Georges in 2013, The Advocate has seen the rest of south Louisiana as rich expansion turf. It launched The New Orleans Advocate (actually shortly before Georges’ purchase) to compete with The Times-Picayune when it cut back print days. It launched the Acadiana Advocate to compete with the declining Daily Advertiser in nearby Lafayette; earlier this year raided the Advertiser’s newsroom to hire away most of its best-known reporters. The Advocate now publishes in three markets stretched out over about 150 miles. And when The Times-Picayune announced it was giving up and selling to Georges last month, it was clear the strategy had some staying power.

It’s interesting to think about in what other markets a strategy like this might make sense. Could Hearst’s Houston Chronicle and San Antonio Express-News decide to go hard for the audience of Austin’s GateHouse-owned daily? Glen Taylor’s Star Tribune looking to reach further into the upper midwest? Would The Seattle Times want to pursue hometown readers in Oregon (where Portland’s Oregonian has also cut print days), eastern Washington, or Idaho? A version of this sort of manifest destiny happened in the 1980s and 1990s, when a few big dailies aspired to distribution across an entire region — but it’s a lot cheaper to try if you’re pushing electrons instead of paper.

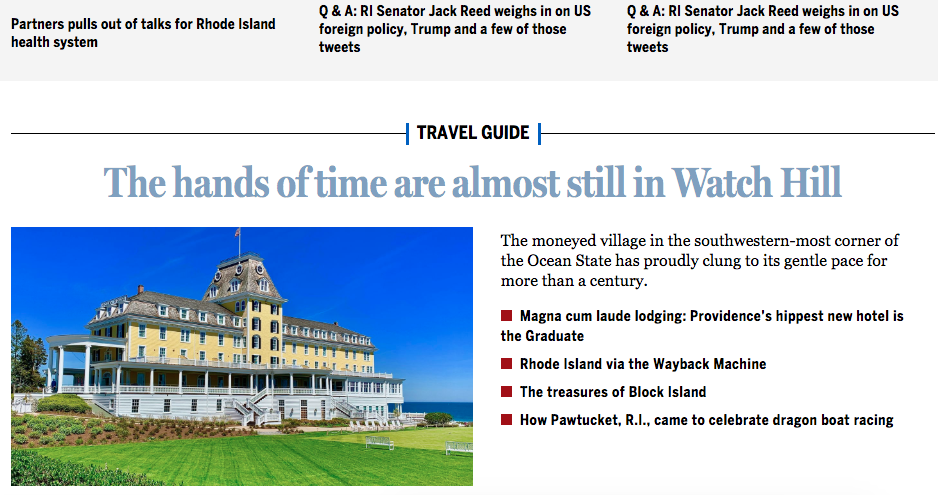

Rhode Island is a first step for the Globe, but McGrory acknowledges they’re considering expanding into more markets in New England. Dan Kennedy originally pointed out that the URL for the vertical, bostonglobe.com/rhodeisland, redirects to bostonglobe.com/metro/new-england/rhodeisland. “The Globe has looked north far more than it’s looked south,” McGrory said, with decent circulation and coverage in Maine and in New Hampshire, especially with the presidential primaries. Many of the potential targets, like Providence, are currently served by GateHouse, which is currently in merger talks and has become well known for its cost-cutting. Just last week, GateHouse announced it was condensing 50 of its Massachusetts weeklies into 18 regional papers.Already the Globe team’s Rhode Island reporting — available in the newsletter, the website, and soon an interview-based podcast — signals that the Globe is aiming for impactful stories that fill in the blanks around what a pinched team at a sliced local outlet might do. There’s also plenty of crime reporting, Milkovits’ specialty. (“We didn’t hire her to be a crime reporter, but hiring her gives us the benefit of seeing what the crime is, and it’s an issue that affects people…on the guttural level,” McGrory said.) And there’s a curious “travel guide” currently featured on the vertical’s landing page that he says is just there while the team builds up content.

“First and foremost, we are writing about Rhode Island for Rhode Islanders,” McGrory said. “We didn’t want to throw people in there from the outside and didn’t want them to think that we’re Bostonians looking at them through a fishbowl.”

So how is The Boston Globe going to convince Rhode Islanders to trust — and maybe even pay money to — their northern neighbor?

Doing the same job I’ve always done.

— Dan McGowan (@DanMcGowan) April 13, 2019

“We had hundreds of new Rhode Island subscribers before we even launched the initiative, just based on word that we had hired these three,” McGrory said. Live events and a Providence newsroom presence will also be part of the concoction. And just doing the regular work of local journalism while living in the same area that they serve as reporters doesn’t hurt. Fitzpatrick caught this scoop while out at lunch:

Lincoln D. Chafee, the Republican-turned-independent-turned-Democrat who served as Rhode Island’s governor and as a US senator, is now a member of the Libertarian Party…A Globe reporter ran into Chafee on Tuesday as he was having lunch at the Wayland Square Diner with his brother, Assistant US Attorney Zechariah Chafee. He said he was back in Rhode Island for his niece’s wedding.