Welcome to Hot Pod, a newsletter about podcasts. This is issue 244, dated February 4, 2020.

New Sony venture. Sony Music Entertainment announced another podcasting venture today, this time in the shape of a partnership with U.K. audio company Somethin’ Else. This continues a recent run of Sony investments in audio — previous examples include Jonathan Hirsch’s Neon Hum Media, Adam Davidson and Laura Mayer’s Three Uncanny Four and Renay Richardson’s Broccoli Content.Somethin’ Else is a slightly different proposition, though, in that it’s a long-established independent media production house. (Neon Hum, Broccoli Content, and ThreeUncannyFour are all new firms.) It was founded back in 1991 and has long been a major supplier of radio shows to the BBC, as well as produced TV shows and branded content. Podcasting has been a more recent development as the U.K. audio market has grown, and so far their output has focused on celebrity-driven shows such as David Tennant Does A Podcast With… and How Did We Get Here? with Claudia Winkleman. Their shows have had partners across the industry, including Spotify, Netflix, and Audible.

I don’t think there’s any remaining doubt that Sony is using this joint-venture strategy to take up a serious position in the podcast industry. That a couple of their investments so far are based in the U.K. feels significant for the market over here — but overall, it’s mostly notable that a music conglomerate is choosing to back so many non-music-related audio ventures. It’s a fascinating dimension to the growing corporate involvement in podcasting that goes beyond the usual Apple vs. Spotify narrative.

Quality control [by Nick Quah]. Over the past week, we’ve seen a noticeable spike in reader emails complaining about the Apple Podcasts platform — specifically about irregularities in the time between uploading an episode and seeing it appear in the Apple Podcasts directory. Which, you know, is an important variable when managing a business contingent on moving product.

At least some of these messages were prompted by the latest edition of a newsletter Apple sends out to individuals who’ve submitted a podcast feed in the past, which contained this section: “Apple routinely checks each podcast RSS feed to detect new episodes as well as metadata or artwork changes. Our system will display these changes on Apple Podcasts within 24 hours after detecting them.”

“Within 24 hours” felt like a vexing hedge, given what that variability implies. One reader who manages a daily podcast expressed anxiety over the uncertainty this can bring to their production: Tuesday morning’s episode might not show up in Apple Podcasts until Wednesday morning? A good number of those reader emails noted that they’ve been experiencing this sort of problem for some time now.

This is a pretty tricky column to write, because when it comes to Apple Podcasts — notoriously a black box — it can be hard to get a full sense of any problem’s size. That was clear in the messages we received, which described a wide range of experiences within the same general dysfunction. One said episodes took 48 hours to appear on the Apple Podcast listings, and a few cited even longer latencies. Some noted that they’d begun seeing the lag in mid-January, while others said it’s been happening as far back as the fall. Some others pointed out another problem, one believed to be longstanding, where episode updates seem to happen more slowly for non-subscribers of a feed than for subscribers — which makes it harder for the podcast publisher to get a clear sense of whether an upload was successful.

At least some readers felt like they weren’t able to get an adequate response, explanation, or acknowledgment from the Apple Podcasts team when they inquired about their situations. And, for what it’s worth, Apple declined to comment for this column.

Historically, I’d have been tempted, for a story like this, to explain it away as just another Apple quirk — something in the vein of, say, the opacity and volatility of its podcast charts or the questionable trustworthiness of its ratings and reviews system. Reality has always been slippery within the Apple Podcasts context — though I suppose that’s also true of internet platforms more generally — and so when I hear about something like this, my gut reaction has been: “Well, that’s just Apple — their mediation of the podcast space has always been kinda weird.”

But that sort of weirdness feels a lot less tenable in a rapidly changing podcast context, fueled by increased financial stakes and the increased platform competition from Spotify. Indeed, it’s getting harder to swallow these technical oddities in the face of any discussion about Spotify vs. Apple rivalry, any speculation of a grand strategy governing Apple’s reported interest in original programming, and any consideration of what appears to be an actual tangible push to expand the Apple Podcasts team. (At this writing, there are 55 open positions at Apple that mention podcasts, including product designers, a server engineer, a business planner, a head of partner relations, a data scientist, an iOS engineer, and a marketing project manager.)

This can’t possibly hold, can it? Something’s gotta change, or something’s gotta give.

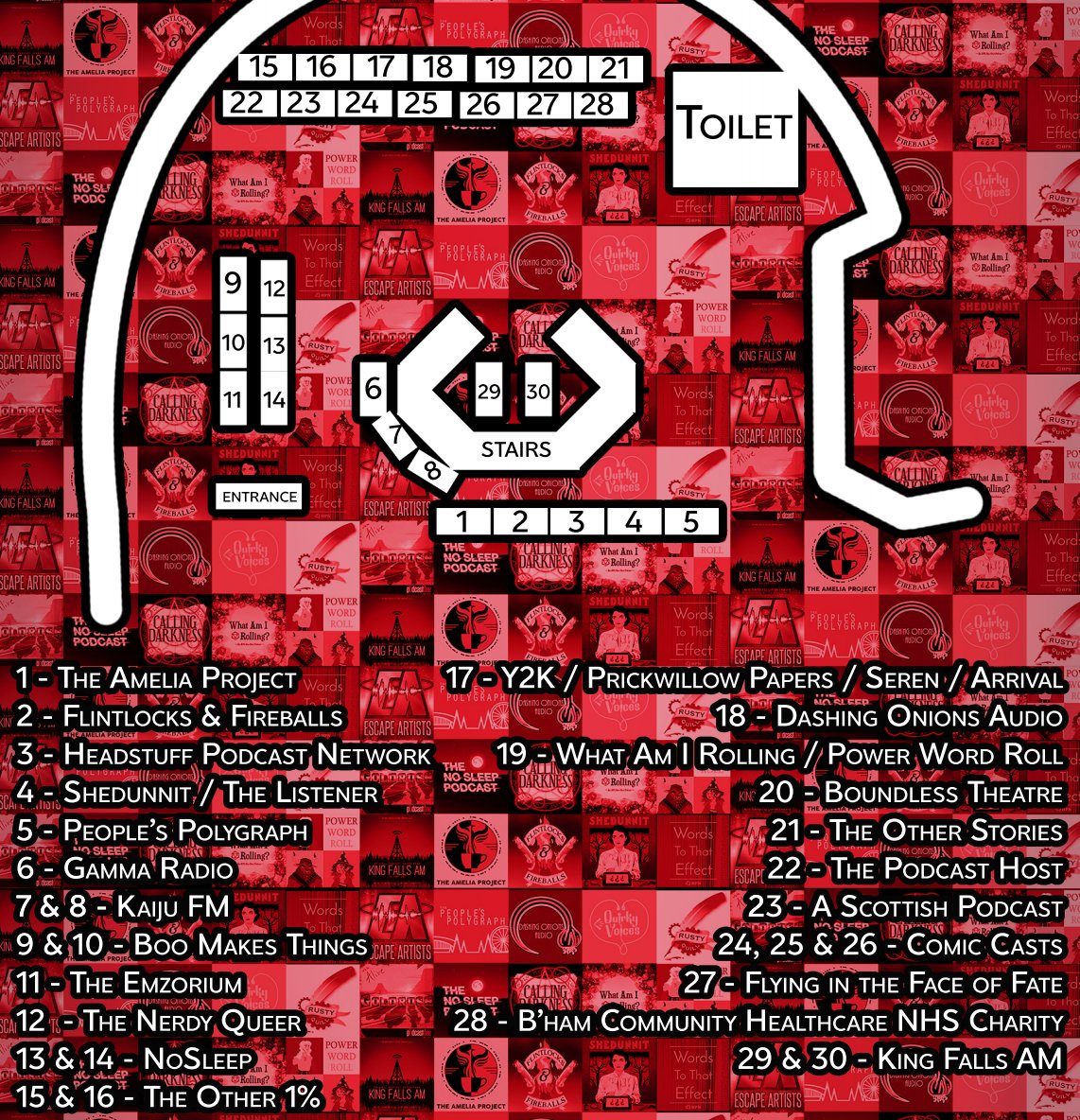

Along with live episodes and workshops, there was a hall where shows could set up stalls. Walking around, I saw a profusion of merchandise on offer — everything from tiny crocheted octopuses and monkeys (an in-joke from the D&D show Flintlocks and Fireballs, apparently) to branded kazoos, along with the more classic badges, stickers, posters, prints, and t-shirts one might expect. Fans were browsing and making purchases, using the merch both as a way to support their favorite shows and to start a conversation IRL with creators.

Selling swag has long been one of the ways podcasters can bring in revenue. That’s perhaps especially true for those operating on a smaller scale or as an independent project. It’s a well-established relationship borrowed from fan-creator relationships in other arenas: For as long as there have been podcasts and people listening to them, there has been merch.

Selling t-shirts and such can integrate well with other forms of direct support — say, by offering a badge in return for a pledge at a certain level on Patreon — or it can exist as a revenue stream on its own. Either way, it’s part of that portfolio of options available to podcasters who either aren’t yet attracting enough listens to make money from advertising or who choose not to go that route. Back in September, I wrote about some of the new startups aiming to capitalize on this connection, and it’s still an interesting growth area. While there’s been plenty of noise around subscription platforms and private feeds recently, I’m not aware of any big effort to disrupt the merchandise space, although perhaps it’s only a matter of time.So what’s the best way to sell podcast merch in this, the year of our lord 2020? How are podcasters grappling with the challenge of converting interest in an intangible audio product into sales of physical goods? And what are the pitfalls of this as a revenue stream?

From talking to podcasters and Hot Pod readers about this cluster of questions, there seem to be two broad options available to the podcaster who wants to start offering merch, and each has its advantages and disadvantages. You can use a third-party service, like Teespring or TeePublic or a whole host of others, and upload designs for them to print on the products of your choice (t-shirts, mugs) as people order them.

The big pro of this dropshipping option is that you aren’t responsible for warehousing and shipping, nor do you have to run a customer-service operation. The downside is that you only get a relatively small cut of the revenue, with most going to the company making and sending your item. This route is high on convenience and relatively low on financial return. Another downside: Depending on your chosen service, you may not get full control over the quality or sourcing of your products — so if things like a transparent supply chain and labor ethics are important to you and your listeners, a dropshipper might slip up in that regard.

There can be unexpected downsides, too. Eric Molinsky, who makes the Imaginary Worlds podcast, told me went the third-party route (with “a well established, mid-sized online print shop”) only to have his listeners balk at the shipping costs. “My listeners were excited until they realized the cost of shipping can be half or a third of the price of the items themselves,” he said. “Everyone’s so used to Amazon prices, or even free shipping with Prime membership, that the sticker shock of what it costs for a small company to ship these items turned a lot of people off.” Ultimately, he managed to negotiate a discount on shipping for his Patreon supporters, but the higher rates remained for everyone else.

The second option? You run the whole show yourself. You work with artists and makers to produce the products you want, and then you keep them in boxes in your home or office, packing and shipping each order as it comes in. The whole thing is flipped from the first option, with the main advantage being full control over your merch and how much profit you take from it. But you’re essentially now running an e-commerce business alongside your podcast.

Ordering and handling your merch yourself also comes with a whole host of issues about stock levels and sizing. Chris Kelly, partner and creative director at the Kelly&Kelly production company in Vancouver, got in touch to tell me about a major miscalculation he once made with t-shirts:

In 2016, we planned a cross-Canada tour for our former CBC podcast/radio show This Is That. We were playing some pretty large venues, so we decided to go big on merch. Or at least t-shirts. We got sooooo many t-shirts, in all sizes. We crunched the numbers and were convinced that we would maybe sell out halfway through the tour.

On that first tour, we sold maybe 20 t-shirts. It took us three years and 40 shows later to finally get rid of all the shirts. By comparison, we published a book in 2017, brought it out on tour, and would sometimes sell 80 in one night. The take away for us was: CBC listeners DO NOT like t-shirts.

This was a recurring theme among those who’d gone the DIY route: You need to be prepared to have a lot of boxes of unwanted merch in your home, for a long time. Jeff Emtman, who makes the Here Be Monsters podcast, told me that the trade-offs between dropshipping and keeping sales in house are something that he and his co-producer go back and forth on every time they launch a new merch item.

“She’s been in the same spacious house for many years, so she volunteered to take care of our merch,” he said. “That being said, she’s also talked about the downsides of living in a warehouse (I mean, I guess it’s not everyone’s dream to live in a commercial space), so we have been transitioning to dropshipping for bulkier items or items which have an uncertain, um, desirability.”

Amanda McLoughlin of the Multitude collective echoed this shift towards a combination of both options. Merch is a big part of what makes their live show tours profitable, bringing in about the same as ticket sales. After trying print-on-demand companies, they now use DFTBA (the e-commerce company owned by YouTubers Hank and John Green) to create and sell their podcasts’ merch. They also work directly with suppliers to create items for the collective’s members and fulfill those in-house.

In the end, it’s all about trading off each approach’s limitations, McLoughlin said: “I researched every single option, and at the end of the day sacrificing some revenue for ease and a better customer experience was worthwhile. DFTBA ships merch items to the cities we’re performing in, we pay friends to work the merch table, and we take home or mail back whatever we don’t sell.”

From all the conversations I had, it seems like this is where we are: There’s no ideal solution on offer, but a combination of dropshipping and personal effort will ultimately do the trick and spread the risk. The big issue for lots of the podcasters I spoke to was design, since audio creators aren’t necessarily also graphic artists, and illustration can be a big outlay on top of the other merch costs.

Something else that came up a lot: how much time this all takes, beyond what’s required to make the podcast itself — whether that’s spent going to the post office several times a week or working with a designer for your dropshipped shirts. Regular readers know this is a bit of a hobby horse for me, the fact that every monetization option seems to require work beyond podcasting itself. It seems that merch is no different from providing bonus content or any other direct-support mechanism: Theoretically, the sky’s the limit on how much you can make — but it’ll cost you a lot of your own time.

The BBC is cutting 450 jobs from its news division, in order to hit its target of finding £80 million of savings by 2022. In addition, two entire TV news programs are also being shuttered — Victoria Derbyshire’s show (which airs on BBC Two and the BBC website) and World Update from the World Service — though, on the whole, executives have tried to trim back teams without taking other shows off the air.

Alongside the announcement of the job cuts, director of news Fran Unsworth signaled a pivot away from traditional broadcasting and toward “modernisation” and digital products. “We need to reshape BBC News for the next decade in a way which saves substantial amounts of money. We are spending too much of our resources on traditional linear broadcasting and not enough on digital,” she said. Part of that involves an internal restructuring so that one team can cover an event for multiple programs rather than having lots of BBC journalists on the same story.

Podcasting is key to this change, too, as part of the effort by the BBC to reach younger audiences with current affairs content. Brexitcast, the political conversation show which topped the BBC’s internal stats release for 2019 Q4, has been rebranded Newscast now that Britain has officially left the EU. A new weekly show about the U.S. election called Americast launches this week alongside the (still up-in-the-air) Iowa caucuses. (The “-cast” suffix as a branding choice for their political podcast stable intrigues me; pun- or portmanteau-based podcast names have traditionally not faired so well with voice assistants on smart speakers. But then again, as the BBC pushes people toward its own BBC Sounds app, perhaps this doesn’t matter so much to them.)

Another major development last week was the announcement by Sarah Sands, editor of BBC Radio 4’s flagship morning current affairs show Today, that she was resigning and would leave the corporation in September. The editorship of Today has been traditionally regarded as one of the biggest jobs in British radio, but I imagine that the application pool might not be as large as it once was — especially since the government has singled out that program particularly for criticism and accusations of “bias.”

Lastly, it was announced Monday that the BBC license fee will go up by £3 on April 1, from £154.50 to £157.50 (just over $200 U.S.). This is part of an annual inflation adjustment implemented by the government in 2017, but it provides yet another news hook on which those wishing to attack the BBC can hang their criticism. The BBC’s own writeup includes a negative response from the Age UK charity and points to the fact that the corporation’s top-paid presenter, Gary Lineker, has recently called for the license fee to become voluntary.

Related: The Times of London has announced that it’s launching its own speech radio station later this year as a direct rival to BBC Radio 4. Times Radio is aiming to “target those disenfranchised by BBC Radio 4 and 5 Live,” and joins several other London-based audio outlets controlled by Rupert Murdoch’s News UK (such as Virgin Radio and talkSport). I think I’ll unpack this news a little more in an Insider later this week, so stay tuned for that.