Editor’s note: The Front Page is a biweekly newsletter from The Objective, a publication that offers reporting, first-person commentary, and reported essays on how journalism has misrepresented or excluded specific communities in coverage, as well as how newsrooms have treated staff from those communities. We happily share each issue with Nieman Lab readers.

This issue is by Holly Piepenburg and Janelle Salanga with a Q&A from Siri Chilukuri and editing by Curtis Yee.

McDonald’s Sausage McMuffins are not the breakfast of champions. They’re the breakfast of white supremacists, according to The Atlantic.

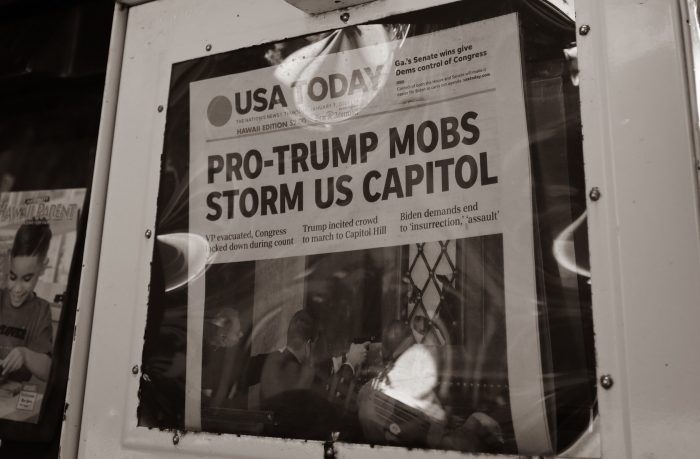

Coverage of the insurrection at the Capitol has varied wildly among outlets and reporters, revealing, yet again, the media’s failure to adequately cover the white supremacy that existed in the United States long before the rise of President Donald Trump. Journalists of color remain unsurprised.

Some have made comparisons to “third-world riots,” like Jake Tapper, who commented, “I feel like I’m talking to a correspondent reporting from Bogotá,” ignoring the reality that mobs had not stormed the Colombian congress for decades, and that America has often incited the violence that prompts people to organize. Alex Kapitan urged people to avoid the words “crazy” and “insane” when describing the violence at the Capitol, given it was a “logical result of Trump’s rhetoric and white supremacy culture.”

Related: A Q&A with Alex Kapitan, a “radical copyeditor”

And there were efforts to marginalize those who stormed the Capitol, like Caitlin Flanagan’s Sausage McMuffin insurrection story in The Atlantic, placing them on the fringes of society with derogatory language, so as to highlight the differences between insurrectionists and other, more cultured white supremacists:

“Here they were, a coalition of the willing: deadbeat dads, YouPorn enthusiasts, slow students, and MMA fans … It would not be hard for a tyrant to compel men like these into violence. Like the original patriots, they were ready to crack heads and convinced they were paying too much in taxes.”

Industry norms sweep white supremacy and racial tension under the table, or shape them into a more palatable package by portraying racists as uneducated societal aberrations.

Our Body Politic host Farai Chideya called out FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver as one of the editors who has “acted like they were protecting the truth from her” to demonstrate how Black journalists’ attempts to cover racial resentment and white nationalism have been routinely shut down. The Associated Press, in its guidance for covering the insurrection, said that reporters should avoid expression of “personal opinion about these political events.”

“Racism has always been about power,” wrote Nikole Hannah-Jones. So has white supremacy. It’s time for industry leaders to recognize elevating largely upper middle-class white male staff gives them the power to shape a narrative — devoid of historical, class and race analysis — that leaves people surprised at the insurrection.

Op-eds shouldn’t incite violence. There is perhaps no better proof of an organization’s unyielding commitment to bothsidesism than a poor op-ed — and there were plenty last year.

Beyond eliciting eye rolls and Twitter ratios, disingenuous opinions often give way to dangerous behavior, as was the case with Vice President Mike Pence’s June op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, which falsely claimed there was no Covid-19 second wave, writes Jacob Sutherland. Rather than address the issue, the publication claimed “cancel culture” was the real problem.

Similarly, The New York Times did not condone, let alone acknowledge, the actions inspired by Senator Tom Cotton’s opinion in an editors’ note, and apologized for little more than “factual questions” and a “needlessly harsh” tone. Why columns are not consistently reviewed under the same editorial standards as the news department is suspect, but eliminating this separation altogether doesn’t have to be the answer. Sutherland writes:

This separation of sections is by no means in and of itself a bad thing. Having a separation of news and editorial staff and leadership helps to ensure that news coverage remains objective.

Publications, however, all too often use this separation between opinion and news sections to deflect criticisms for controversial pieces, avoiding accountability for both reprehensible opinions and factually inaccurate arguments, which dilutes trust of the publication as a whole.

Realistically, if outlets take measures to ensure readers know the difference between the two sides, publications may be able to continue publishing their beloved op-eds — as long as they don’t inspire violence or disregard facts.

You can read more here.

Anna Wintour responds to Vogue cover. On Tuesday, The New York Times published an interview with Anna Wintour, in which the longtime Vogue editor-in-chief addressed controversy over this February’s cover featuring Vice President-elect Kamala Harris.

Wintour said she understands the reaction to the cover — which many have called disrespectful due to its informality and apparent lack of reverence — but did not aim “to in any way diminish the importance of the Vice President-elect’s incredible victory.” Additionally, she said there was no formal agreement about the cover, which contradicts the Harris team’s claim.

It might be easier to accept Wintour’s explanation if a similar blunder had not been made six months ago with the release of another unflattering cover featuring gymnast Simone Biles.

.@voguemagazine is hot arse mess. Kamala Harris print cover is not visually on par w/what V cover epitomizes and visuals audiences expect. It’s a snap w/crinkled drape. Didn’t they learn from their Simone Biles cover?

Respect Black Women.

My comment is not re: subject herself. pic.twitter.com/SclqacQz9p

— Sarah Glover (@sarah4nabj) January 10, 2021

Even if Wintour did not intend to select the less powerful image, her inclination to select a photo that presented Harris as “welcoming and relaxed” speaks volumes about her bias, which has been covered extensively in recent years. Wintour says the magazine “is extremely committed to diversity, and inclusion, and to listening to everyone,” but puts an emphasis on the Vice President-elect looking “approachable.” Do recent pandemic-era covers evoke the same warm feelings?

Q&A: Chika Ekemezie on the difference between writers and journalists. Large barriers still exist to entering the media industry. There has been a concerted effort to try to change this, as evidenced by the amount of upstart newsletters, new union membership, nonprofit newsrooms, media collectives, and worker-owned co-ops that have emerged in the past few years.

These entities are trying to put the power back into the hands of media workers, rather than the few people who run media conglomerates, and empower people to work together while navigating the journalism industry.

Study Hall is one such entity; it has been expanding ever since its inception in 2015, and now offers a Slack, email listserv, and webinars. The team also recently hired freelancer Chika Ekemezie as a part-time operations manager to help the team manage all its moving parts.The Objective sat down with Ekemezie to talk about professionalism, the difference between being a “writer” and a “journalist,” and how Study Hall helps remove barriers to entering the media. You can read the rest here.

The Objective: What does objectivity mean to you?

Chika Ekemezie: For awhile, I was focused on policy and law and I thought I was gonna go to law school, so objectivity is something that I always struggled with, even then. It doesn’t mean anything, It means an objective person would think this, would think that. Objectivity is what we consider normal, which is whiteness, which is maleness, which is a tendency towards logic and rational decisions and taking emotion out of it. Being objective means you’re not emotional, but I just don’t think that’s right or that’s necessarily important when we make decisions or we think about how to write things.

What’s happening. $$$ denotes a paid event.

A bit more media.