Editor’s note: Longtime Nieman Lab readers know the bylines of Mark Coddington and Seth Lewis. Mark wrote the weekly This Week in Review column for us from 2010 to 2014; Seth’s written for us off and on since 2010. Together they’ve launched a monthly newsletter on recent academic research around journalism. It’s called RQ1 and we’re happy to bring each issue to you here at Nieman Lab.

“Stick to sports”: Evidence from sports media on the origins and consequences of newly politicized attitudes. By Erik Peterson and Manuela Muñoz, in Political Communication.

How do people come to see areas of society, or media sources, as political where they hadn’t before? That’s the question Peterson and Muñoz are addressing in this study, and it’s one that many of us have wondered over the past several years, as subjects like vaccines and Dr. Seuss have become widely perceived as fundamentally political ones.

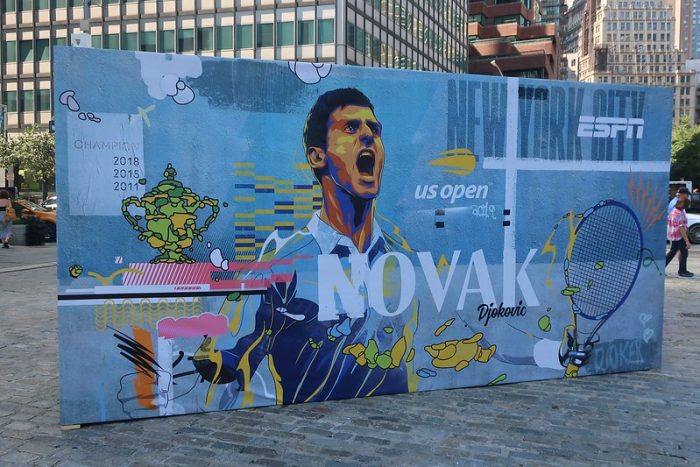

Peterson and Muñoz examine an interesting example in the sports broadcasting behemoth ESPN, which has seen its longstanding apolitical perception dramatically shift in the face of sustained conservative attacks on its impartiality over the past decade.

The authors hypothesize two potential routes to politicized attitudes about ESPN: viewing it as political because they perceive public opinion (and especially conservative media) as seeing it as political, and viewing it as political because of their actual experience with ESPN content. They also try to determine if politicization makes people more likely to reduce their consumption of ESPN.

Peterson and Muñoz address these issues in a remarkably thorough article consisting of three studies — two survey-experiments and a third survey. They find that people are much more likely to see ESPN as political based on consumption of political (i.e., conservative) media with commentary about ESPN than based on actually watching ESPN.

But the influence of these partisan media-induced cues doesn’t extend into action. The authors found no partisan differences in ESPN use during a time (2016-17) when they found massive partisan differences in perceptions of ESPN. (The biggest factor driving ESPN use was, of course, interest in sports.) Partisan media, they suggest, may be very effective at generating antipathy toward media sources, but much less so at changing media consumption behavior.

How investigative journalists around the world adopt innovative digital practices. By Jessica Kunert, Jannis Frech, Michael Brüggemann, Volker Lilienthal, and Wiebke Loosen, in Journalism Studies.

Investigative journalism has had a conflicted relationship with technology. It’s often seen as one of the least technologically reliant subdisciplines of journalism — the domain of “pounding the pavement” — but it’s been much more closely tied to data journalism over the past decade.

Kunert and her coauthors took an international look at how investigative journalists adopt and adapt to technology, interviewing 133 investigative journalists from 60 countries and analyzing the results through the lens of the diffusion of innovations, one of communication studies’ longest-standing theories.

They found that while investigative journalists are hungry to learn about new technological aids to their work, “they are overwhelmed with acquiring digital skills and feel helpless in the light of the complexity of the digital practices that are potentially at their disposal.” To cope, they often collaborate with specialists — largely technologists — and hang onto some traditional methods.

But the authors also found that social structures affect adoption far more than diffusion of innovations has typically held. Specifically, they characterize investigative journalism as a social system operating at two different speeds, with those in Global South dramatically limited in their ability to access advanced digital tools. “The gap between South and North is widening,” they wrote. “While in the Global North more and more digital practices are becoming part of everyday work in the newsroom, the Global South often continues to struggle with the preconditions for the use of digital practices.”

Harassment of journalists and its aftermath: Anti-press violence, psychological suffering, and an internal chilling effect. By Changwook Kim and Wooyeol Shin, in Digital Journalism.

Journalists around the world have been subject to increased amounts of derogatory rhetoric, harassment, and violence over the past decade. A wave of recent studies has examined the effects of that harassment on journalists, finding that it tends to make journalists less willing to pursue emotionally oriented tasks, cover particular types of stories, and view audiences as rational.

Kim and Shin provide a notable addition to these studies by examine the psychological and emotional effects of harassment and coping mechanisms among journalists in South Korea, where anti-press sentiment is severe. They argue that anti-press discourse has been normalized through the widespread adoption of the word giraegi, a portmanteau of the Korean words for “journalist” and “trash,” and the violent and abusive rhetoric around it.

Kim and Shin conducted interviews with 10 journalists and an analysis of 18 self-reflective articles written by journalists in response to harassment. They found that harassment, which is especially intense against women, produces senses of anger, helplessness, and fear in journalists. They try to cope through perfectionism (which isn’t effective, since the harassment rarely comes in response to actual mistakes), putting emotional boundaries between themselves and audiences, and ‘counter-hating’ and belittling them.

Kim and Shin also found that journalists are vulnerable to “mob censorship” when their organizations don’t support them against such attacks, leading journalists to choose not to pursue certain types of stories for fear of angering audiences. They conclude by posing a stark question: “Should journalists serve members of the public who deny the reason for their existence?”

Do more with less: Minimizing competitive tensions in collaborative local journalism.” By Joy Jenkins and Lucas Graves, in Digital Journalism.

Collaborative journalism has created a lot of buzz in both the profession and the academy as a means for news organizations (particularly under-resourced ones) to undertake projects and achieve impact they couldn’t otherwise. But it can be difficult in practice, especially when the organizations involved have strong competitive interests with their newfound partners.

Jenkins and Graves sought to illustrate some potential solutions to these problems through three case studies of local journalistic collaboration in Europe. Through each case, they outlined a different collaborative model: co-op, contractor, and NGO.

In the co-op model, similar news organizations (a group of 11 Finnish daily newspapers) agree to collaborate only on specific topics in which they don’t compete. The contractor model (based on a collaboration between an Italian newspaper publisher and two startups) is structured through a contract in which organizations specialize in different areas. And in the NGO model (built around a British nonprofit news organization), a coordinating nonprofit manages common data through which many outlets develop their own stories.

For each model, Jenkins and Graves detailed the main level on which tension is alleviated — the topic, the role, or the story. While each differed on where competitive tension lay and how it was resolved, each one, the authors concluded, represented a sustainable path for local collaborations among news organizations.

Recommended for you: How newspapers normalize algorithmic news recommendation to fit their gatekeeping role. By Lynge Asbjørn Møller, in Journalism Studies.

From Digital Journalism:

We’re in this together: A multi-stakeholder approach for news recommenders. By Annelien Smets, Jonathan Hendrickx, and Pieter Ballon.

Between personal and public interest: How algorithmic news recommendation reconciles with journalism as an ideology. By Lynge Asbjørn Møller.

To nudge or not to nudge: News recommendation as a tool to achieve online media pluralism. By Judith Vermeulen.

Benefits of diverse news recommendations for democracy: A user study. By Lucien Heitz et al.

Five articles on news recommendations have been published this month — four by Digital Journalism (part of a forthcoming special issue on AI and journalism), and one by Journalism Studies. Together, they form a fascinating deep dive into what role algorithmic news recommendation systems are playing in the professional world of journalists and our political and social structures more broadly.

The studies by Møller (in Journalism Studies) and Smets et al. both examine how algorithmic recommendation systems are implemented by journalists, and both find that news organizations remain cautious in their use of recommendations out of a concern for maintaining traditional gatekeeping control and the kind of autonomy that comes with manual decision-making.

Møller looks at how Scandinavian newspapers have incorporated editorial control into their recommendation products, and Smets et al., based on interviews with media professionals in the Flanders region of Belgium, propose a model that takes into account the perspective of numerous stakeholders including users and management.

Møller’s other article looks more broadly at the tensions between journalistic values and news recommendation technology, arguing that journalists can navigate that conflict by emphasizing diversity, serendipity, and editorial input in designing recommendations. Vermeulen, meanwhile, reflects on a parallel set of tensions on the users’ side — between nudging users toward higher-quality news and preserving their autonomy and choice.

Finally, Heitz and his colleagues built an app aggregating and recommending news from Swiss outlets to test the effects of news recommendations on exposure to different viewpoints and polarization. They found some indications that diverse recommendations increase openness toward opposing views and appreciation of journalism, but no effect on political knowledge or participation.

This is the second of what we hope will be occasional summaries by RQ1 readers of notable recent books on news and journalism. This month’s summary is from Erin Siegal McIntyre, a professor at the University of North Carolina who previously worked as a journalist based in Tijuana. If there’s a recent research-oriented book on news or journalism that you’d like to write about, let us know!

“In Mexico, undoubtedly, too many journalists have died, but journalism is far from dead.”

While that sentiment may be true, at least so far in 2022, the murder of reporters in Mexico has broken record after record.

This grim reality makes Surviving Mexico: Resistance and Resilience among Journalists in the Twenty-First Century, the new 288-page book by Celeste González de Bustamante and Jeannine E. Relly, even more urgently indispensable. For the last twenty years, Mexico has “fade[d] from a hopeful moment into an era of tumult and fear,” the authors note, despite “finally reach[ing] some level of democracy” after seven decades of semi-authoritarian rule.

Based on more than 160 interviews with journalists, activists, and academics across several regions of the country, González de Bustamante and Relly present a highly readable account of the myriad dangers faced by journalists in Mexico, the impact of trauma and violence on their lives, and how individuals and collectives have organized to meet the challenges of working in such a dangerous place. Journalists are more vulnerable, so they’ve been forced to develop new mechanisms by which to cope and survive.

While the first two sections of the book focus on anchoring and quantifying violence, the third and final section offers a refreshing long gaze toward the future. Building resiliency is key to basic survival. Drawing clear connections between resistance and resilience, González de Bustamante and Relly outline various ways that journalists in various Mexican states and cities have come together, formally and informally, to protest, resist, and organize.

“Changing course will require enormous effort in tandem with the will of all sectors of society,” they write. “Some journalists and activists have started down that road … [and] many more must join them for real change to happen.”