Last week, Oxford’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism released its annual report on digital news, which we covered broadly here. Below, Kirsten Eddy, a research fellow at RISJ, pulled out some of her findings on how young people consume news.

Media organizations around the world can agree on one thing: Young people — despite being critical audiences for publishers and journalists, and to the sustainability of news — are increasingly hard to reach and engage.

Using data from the 2022 Reuters Institute Digital News Report, we show that younger audiences increasingly consume and think about news differently than older audiences do. They are more casual news users, rely more on social media, and are less connected to (and therefore less loyal to) news brands. They also have different perceptions of what news is and how it’s practiced.Of course, it’s long been the case that young people’s behaviors and preferences are different from those of their older peers. They long have been.

But as more young adults who grew up with social media enter our sample, the differences seem to be growing, even between social natives — those aged 18–24, who largely grew up with social media — and digital natives, those aged 25-34, who largely grew up with the web but before the rise of social networks. Many of these shifts are so fundamental that it doesn’t seem likely that they will be reversed with time.

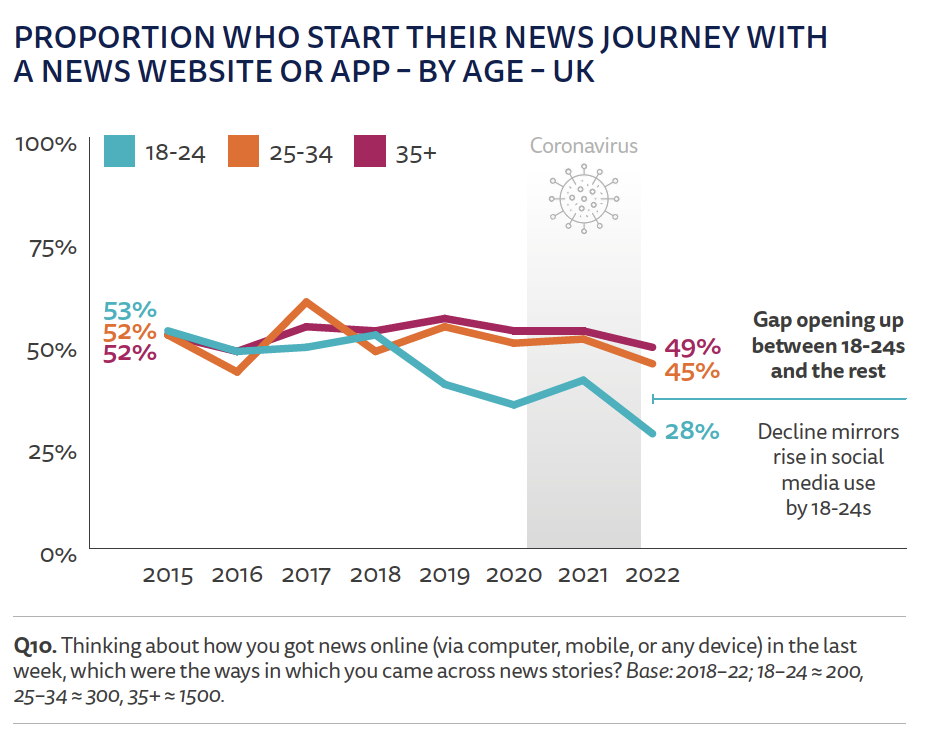

As we track people’s main sources of news over time, we find direct access to news apps and websites steadily becoming less important and social media becoming more important. These changes are largely driven by the emerging habits of social natives (18-24s) as they come into adulthood and don’t often form strong brand connections.

When we look at main access by age in the U.K., for instance, we see social natives (turquoise line) have become significantly less likely to use a news website/app — differing not just from the oldest groups but also from digital natives. This group is far more likely to access news using “side-door” sources such as social media, aggregators, and search engines than their older peers.

As the social media landscape continues to evolve dramatically, social natives have also shifted their attention away from Facebook — or never started using it in the first place. In its stead, visual platforms such as Instagram and TikTok have become increasingly popular for news use among this group. On average across 46 markets, social natives are now five times more likely to use TikTok for news in 2022 (15%) than they were in 2020 (3%). Here’s the data for the U.S.:

These patterns do not hold up for all young people. While digital natives have largely embraced many of the same networks, they remain far more loyal to Facebook, the network this cohort largely grew up with, and have been slower to move to new networks like TikTok.

And despite the meteoric rise of online video formats, text- and audio-based formats still have a big role to play in young people’s news habits. Under-35s still largely say they prefer to mostly read (58%) rather than mostly watch (15%) news. Some seek out a mix of formats to better understand information, while others are drawn to audio-based formats like podcasts that allow users to multitask while they listen. There is not a one-size-fits-all approach or medium through which newsrooms can attract younger audiences.

Young people — particularly social natives — don’t just have different news behaviors than older groups. They also have different attitudes toward the news and how it’s practiced. They are more likely than older groups to believe media organizations should take a stand on issues like climate change and to think journalists should be free to express their personal views on social media.

Many young people also have a wider definition of what news is. We find younger audiences often distinguish between “the news” as the narrow agenda of politics and current affairs and “news” as a wider umbrella encompassing topics like sports, entertainment, celebrity gossip, culture, and science. Under-35s are less interested than older groups in what they consider to be “the news” — traditional beats like politics, international, or Covid-19 news — and are more interested in a broader array of “news” umbrella topics, including entertainment and celebrity, education, and fun news.

But contrary to conventional narratives of “young people” as socially engaged digital activists, particularly when it comes to climate change, mental health, and social justice issues, we don’t find greater interest in news specifically about these topics among young people broadly.

Instead, younger audiences’ interest in these topics varies dramatically by country and demographics. For example, interest in social justice news is 9 percentage points higher among under-35s than those 35 and older in the U.K., on a par across both groups in Brazil, and 7 percentage points lower among under-35s in Germany. And, on average, older groups are more likely than younger groups to say they are interested in environment and climate change news.

As more news outlets and formats compete for audiences’ time and attention, we continue to see longer-term falls in interest and trust in news across age groups and markets — particularly among younger audiences, who are generally less interested in news, access it less frequently, and actively avoid it more often than older audiences. On average across all 46 markets, around four in ten social natives (40%) and digital natives (42%) often or sometimes actively avoid the news.

Even those who remain engaged with news increasingly choose to ration their exposure to it — not often necessarily avoiding all news, but instead avoiding specific topics. Most often, younger audiences (43% of under-35s) say they avoid the news because there is too much coverage of topics like politics and Covid-19. We call this behavior selective news avoidance, and while this is not limited to younger audiences, we see substantial rises in avoidance among social natives, in particular, since we last asked this question in 2019.

The longstanding criticism of the depressing or overwhelming nature of news also persists among younger audiences. Our interviewees mentioned forming news habits to avoid negativity: “I tend to try and limit the amount of negative news I consume, especially first thing in the morning and last thing at night,” a 29-year-old U.K. woman said.

And we find that younger people — particularly social natives — are more likely than older groups to say they find the news hard to follow or understand. In moments of crisis, such as the pandemic or the Ukraine war, we’ve seen some news outlets using explainer and Q&A formats to try to address these issues. Our data suggest this process needs to go much further.

Over time, key differences among (and within) younger news audiences continue to become clearer. Social natives’ reliance on social media and weak connection with brands make it harder for media organizations to attract and engage the newest group of news consumers. At the same time, young people’s perceptions of what news is are also wider. And while these groups do not all have the same needs, many are looking for more diverse agendas and voices and for stories that don’t depress or confuse them.

Recognizing the variety of preferences and tastes that exist within these incredibly diverse cohorts presents a new set of challenges and opportunities for media organizations. But it is clear that news brands can’t expect young people to eventually come around to what has always been done.

Kirsten Eddy is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, a senior researcher with the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, and a research affiliate with UNC’s Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life.