Any regular viewer of BBC’s Question Time could be forgiven for thinking that old-fashioned climate science denialism is alive and kicking. In a recent edition, panelist Julia Hartley-Brewer called the IPCC’s climate models “complete nonsense,” and dismissed the 2022 record U.K. heatwave and the floods in Pakistan by saying: “It’s called weather.”

But for some time now, researchers have suggested that the balance of arguments propagated by climate skeptics or denialists has shifted from denying or undermining climate science to challenging policy solutions designed to reduce emissions.

For example, computer-assisted methods applied to thousands of contrarian blogs or websites have found that since the year 2000, “evidence skepticism” — which argues that climate change is not happening, or is not caused by humans, or the effects won’t be too bad — has been on the decline, while “response” or “solutions skepticism” has been on the rise.

In the U.S. media and U.K. media, there is strong evidence too that the prevalence of these arguments may be shifting. By 2019, much less space was being given to those denying the science in newspaper outlets in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the U.K., and the U.S., except in some right-leaning titles.

But what about television coverage? Recent survey work finds that in most countries, television programs, including news and documentaries, are by far the most used source of information on climate change compared to online news, print or radio.

In a new study published in Communications Earth & Environment, my colleagues and I looked at 30 news programs on 20 channels in Australia, Brazil, Sweden, the U.K., and the U.S. which included coverage of a 2021 report by the IPCC on the physical science basis of climate change. Australia, the U.K., and the U.S. were chosen for their long history of climate skepticism, whereas Brazil and Sweden were included for the more recent arrival of skepticism among key political parties.

These channels included 19 “mainstream” examples such as the BBC, ABC in Australia, and NBC in America, and 11 examples from a selection of “right-wing” channels ranging from Fox News, which commands a large audience, to more outliers such as GBTV in the U.K., SwebbTV in Sweden, Sky News in Australia and Rede TV! in Brazil.

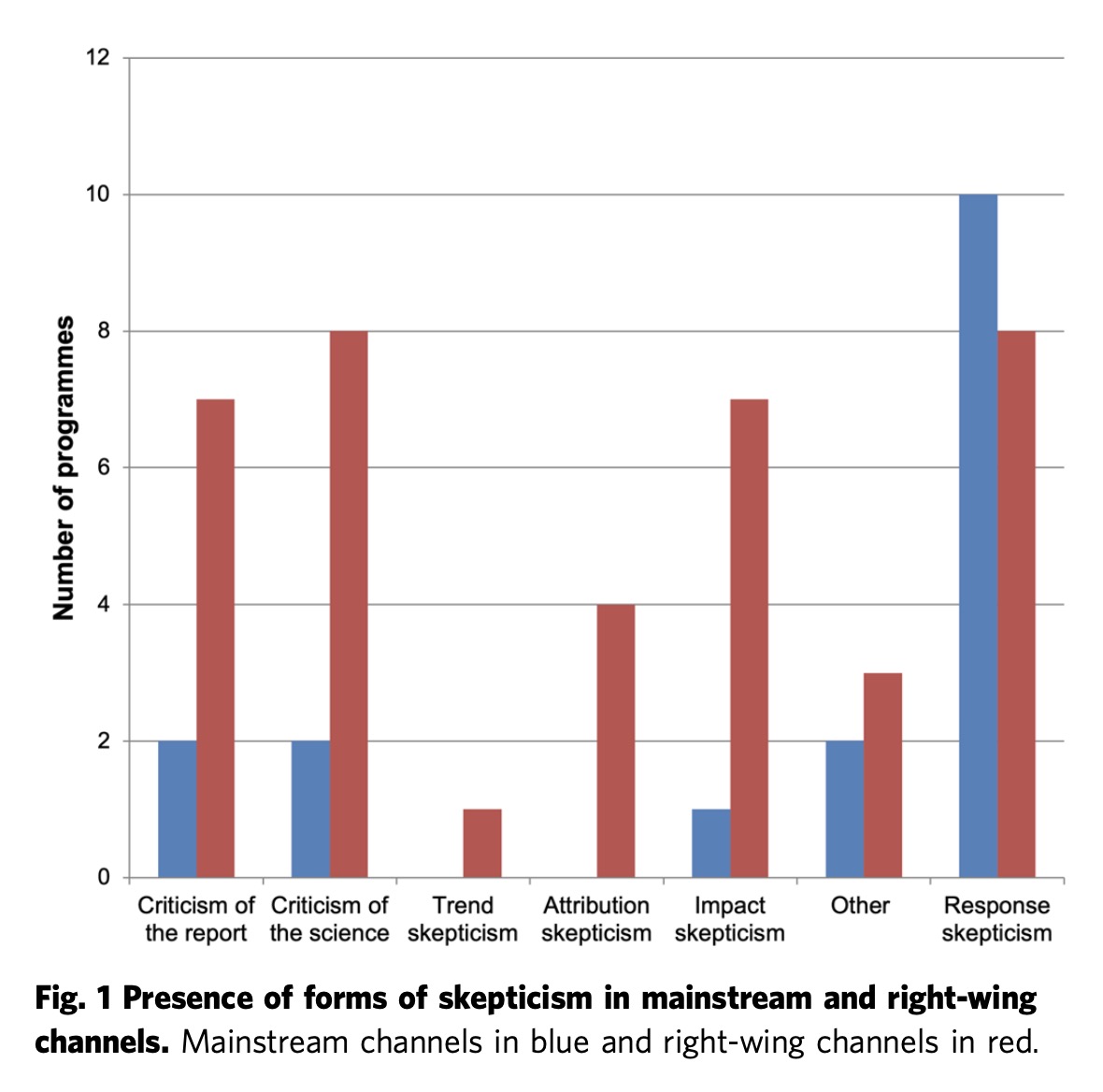

We then watched and manually coded all 30 programs (around 220 minutes of content) for examples of the different types of skepticism present, following the broad distinction above between “evidence” and “response/policy” skepticism. But we also distinguished between “general response” skepticism — usually advanced by organized skeptical groups — and “directed” response skepticism, where country-specific economic, social, and political obstacles to enacting climate policies were mentioned.

First, we found that on mainstream channels, the presence of science skepticism, science skeptics, and general contestation around the IPCC’s report was much less present in our sample than in the coverage of the previous round of IPCC reports in 2013 and 2014, even in countries that have historically had strong traditions of science denial.

Second, response skepticism was in some of the coverage by mainstream channels. But in most cases, these were examples of “directed” skepticism. In contrast, there was more non-specific response skepticism on right-wing channels such as right-wing politician and pro-Brexit campaigner Nigel Farage on GBTV arguing that “whatever we do here [in the U.K.], it’s China that needs to do far more than us,” or a commentator on Fox News suggesting that “only being able to fly when it is morally justifiable would lead to people having to entirely change their lifestyles”.

Also, on right-wing channels in four countries (Australia, Sweden, the U.K., and the U.S.), skeptics were combining evidence and response skepticism. For example, Fox News continued its historical record of skepticism by criticizing the IPCC report and hosting evidence skeptics, but it also included a wide range of examples of response skepticism (such as the infringement on civil liberties by taking climate action).

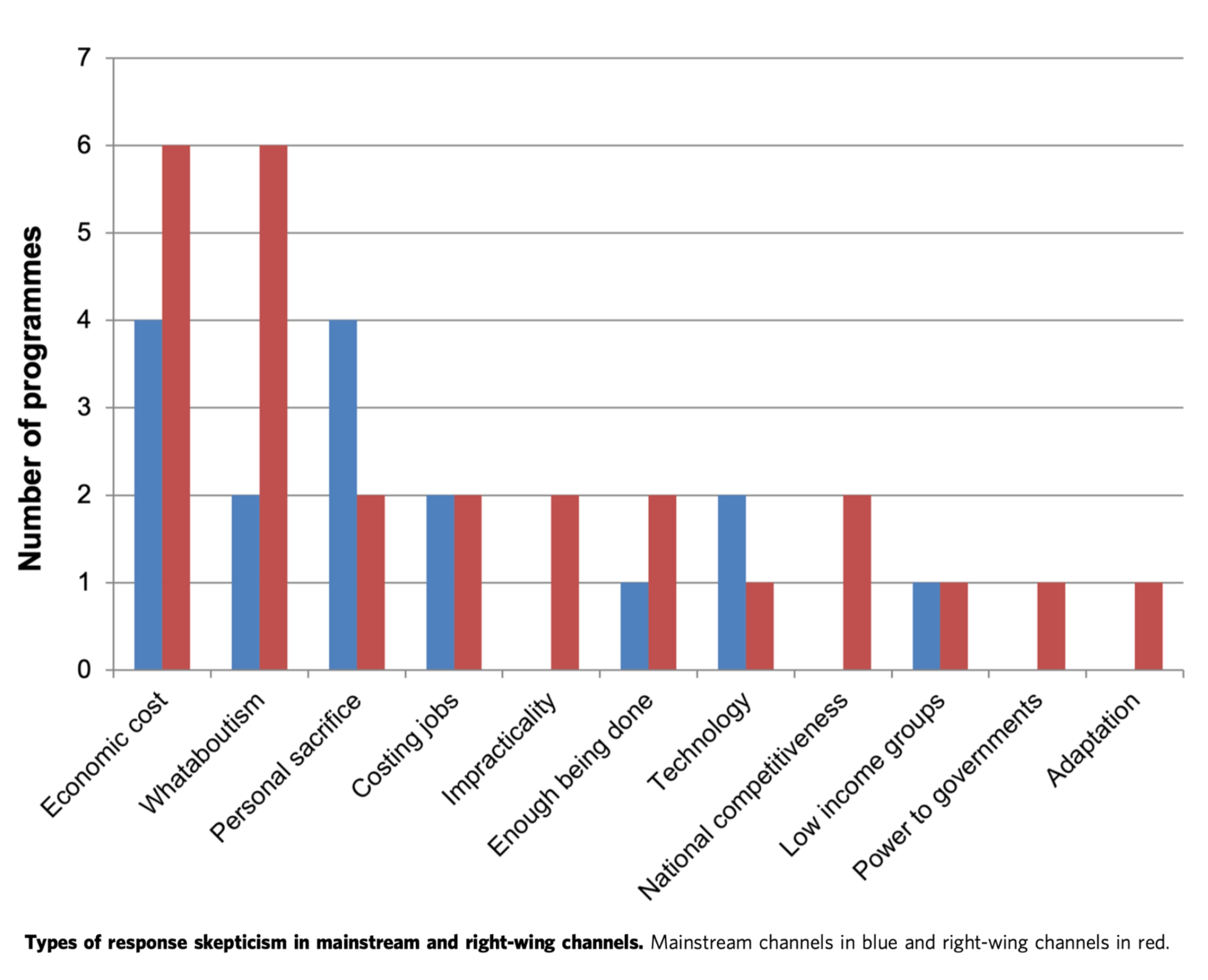

Finally, we looked at the sorts of arguments that were being made, following a useful taxonomy of climate skepticism or obstructionism published in the journal Nature in 2021. We found a wide variety of claims, but the most common concerned the high cost of taking action and “whataboutism” (typically questioning the need to take action when other countries such as China were not doing enough).

Why does this matter? First, how these arguments play out on television is hugely important because of its dominance as a source of climate information. Second, there is strong evidence that media has a very powerful agenda-setting effect, and in certain contexts, can exert a strong effect on attitudes and behavior change.

Legitimate policy discussion needs to be carefully distinguished from false claims put out by organized skeptical groups. But for those active in opposing organized skepticism, any definitive shift towards response skepticism across the media, such as vocal opposition to net zero policies, represents an important new challenge to climate action.

James Painter is a research associate at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.![]()