U-T publisher Jeff Light sounded not just optimistic, but even a little boastful as he unveiled the experiment, part of his attempt to transition what’s left of the old legacy newspaper to a digital future.

“The Union-Tribune is a profitable business and, and also profitable, I guess I will indulge and say, in the right way,” Light said in a Q&A in the U-T.

“So there are some newspaper companies that are sort of dissolving the franchise as they go forward and harvesting money out of the business to send profits to their owners,” he said. “That’s not what’s going on in San Diego.”

Light didn’t name any company directly, but anyone in the media industry knew precisely who he was talking about: Alden Global Capital, a hedge fund that has for the last half decade been gobbling up distressed local newspapers and relentlessly pillaging them.

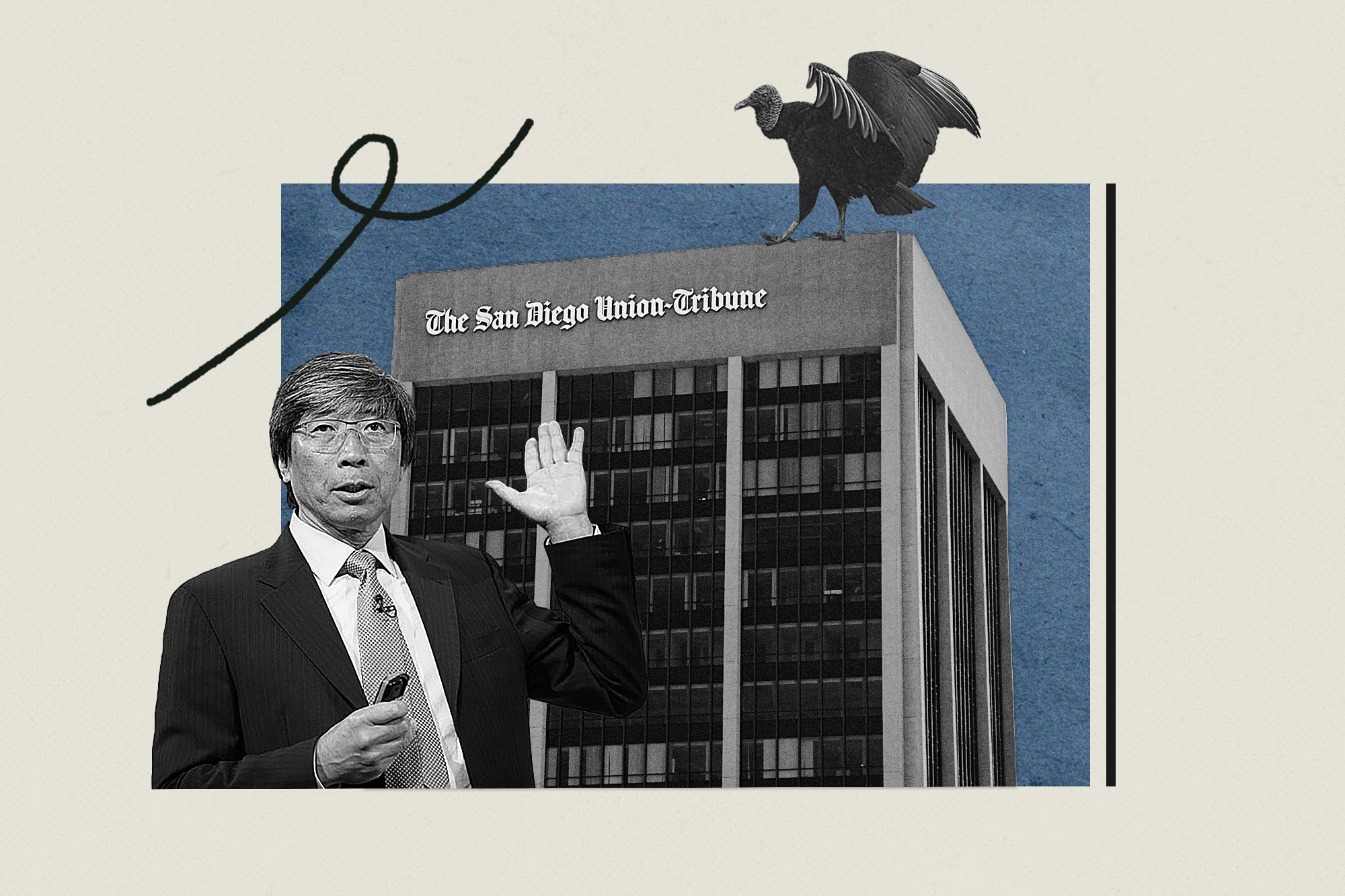

So it must have been particularly gutting when, a year later, Light got a call on the first Monday after the Fourth of July to break the news: Patrick Soon-Shiong, the owner he’d called “really enlightened” in that interview, had suddenly sold the newspaper. And he’d sold it to Alden.

Everything moved so fast after that. Within an hour or so, U-T employees got an email informing them of the sale.

Just like that, one of Alden’s key guys was there that afternoon, walking around the mostly empty newsroom with the newspaper’s security guy, wandering over to the few populated cubicles to ask people what they did. His name was Ron Hasse, and he was wearing a very nice suit. He had a shaved head and a close cropped beard and spoke like he’d been pre-programmed by corporate.

It was a lot. Not only was there suddenly a new owner, the most terrifying owner in American journalism, but their guy was already in the building. Alden was already doing its thing: minutes after the main announcement, employees learned there would be staff cuts. They had a week to decide whether they wanted to apply for a buyout package.

When Alden showed up in other cities in recent years, journalists and their supporters had time to mobilize an opposition. In Chicago, Tribune reporters turned their investigative focus to their new prospective owners in an effort to raise the alarm. In Baltimore, Sun reporters had organized a “Save Our Sun” campaign to try to find an alternative owner. They ultimately failed, but it led to the creation of one of the most well-funded local news nonprofits.

Likewise, in all the other sales the U-T has endured, there’d been little secret the paper was on the market. This time, Alden appeared with no warning. One morning, everything was normal. Minutes later, San Diegans were processing, yet again, what a new owner would do to their largest source of news and information. This one came with a variety of colorful monikers: the grim reaper of journalism, the men who are killing newspapers, strip-miners, vampires and vultures — all reputations they do little to dispel.

U-T employees, meanwhile, were wondering whether they still had a job and, if they did, under what conditions. Working for Alden brings with it not just job insecurity, but also actual health hazards: In the Philadelphia suburbs, workers at an Alden-owned paper said they navigated gross bathrooms, rats, mildew and fallen ceilings. In Denver, where Alden cut the newspaper staff by at least 75 percent, employees that remained reported breathing problems after being moved to a plant with poor air quality. In Monterey, Calif., the hot water got cut from the bathrooms.

The first all-staff meeting 10 days later did little to ease anyone’s jitters. Hasse did what Alden typically does with its employees and the interested public: He didn’t give them much detail at all. No editorial direction. No idea of how many people Alden would cut or what the organization would look like on the other side. He spoke for about 20 minutes and didn’t take any questions.

“He’s probably just doing his job, which is to not give us as much info as possible,” said one employee at the time.

More than one person jokingly wondered if Hasse was even real.

“If you would’ve told me he was an AI-generated bot I would’ve believed you,” the employee said. “He didn’t seem human.”

For more than eight decades, the newspaper was run by one family: the Copleys. For the most part, the family owners held a fondness for the status quo and nursed a coziness with power brokers, fostering a paper that wasn’t as bold and ambitious as many of its big city counterparts.

Still, it was a newspaper. It was big and important and it employed a lot of journalists at one point, and many of them were quite good. The paper won a Pulitzer Prize in 2006 for a stunning investigation that sent Congressman Randy “Duke” Cunningham to prison for spectacular corruption. It had bureaus in Washington, D.C. and Mexico City. Even when it wasn’t great, it was at least there: watching meetings of the City Council, school board, supervisors, Port of San Diego and more.

Things started to get ugly around 2007 as the newspaper business model collapsed, just as the global economy did the same. Craigslist ended the papers’ near monopoly on classifieds and Google and Facebook were beginning to provide advertisers with a far superior way for local businesses to reach potential customers.

Facing this sudden shift in its fortunes, the family sold the paper in 2009 to Platinum Equity, who did what private equity guys do to their distressed assets, immediately laying off nearly 20 percent of the staff. In just two years, the U-T — which once employed nearly 1,500 people — had lost 40 percent of its staff, mirroring its precipitous drop in advertising revenues. The company brought in Light to run the newsroom, a position he would maintain and expand on throughout the succession of owners.

Over this time, newspapers responded to all the upheaval with the kind of short-term decisions that panic can induce: They continued to cut staff and degrade the user experience, larding up their websites with graphic pop-up ads for toenail fungus removers and chasing clicks. The business model was a mess and the product was getting worse.

Then came the flamboyant local billionaire owner, Doug Manchester, in 2011. Manchester turned the paper into a den of sexism and harassment, according to a Washington Post story that only came about once Manchester was nominated to an ambassadorship under President Donald Trump. Manchester changed the name (U-T San Diego), gave it a ridiculous motto (World’s Greatest Country and America’s Finest City), turned it into a TV channel (U-T TV), installed a bedroom and an antique car museum in the office, came up with his own plan for a Chargers stadium, insisted people continue to call him by his sleazy nickname (which won’t be repeated here), to name a handful.

The Manchester era didn’t last too long, and he eventually sold four years later to the Tribune Company, a formerly august newspaper chain that, in one of the most legendarily unintentionally hilarious PR videos in the history of the internet, rebranded itself as a technology company by the name of Tronc.

So it was remarkable that over the last few years the U-T had settled into something that seemed like not just stability, but perhaps even success under its Soon-Shiong, a billionaire Los Angeles doctor/entrepreneur who’d made billions developing a cancer drug and selling two pharmaceutical companies before buying the Los Angeles Times and, as part of the deal, taking on the U-T.

The journalism was better, more ambitious and interesting. The newsroom was far smaller than it had been (108 employees, down from 400 in 2006), but longtime reporter Greg Moran, who’d been there since the golden years thought, pound for pound, it’d become the best ever version of the U-T. From what employees were told, the paper was profitable. Local newspapers had abandoned the click-race to the bottom, and instead shifted to a subscription model that relied on quality, not quantity. Without their old revenue streams, they had to create a product online that was good enough for people to pay for directly — aligning their financial model more directly with their product.

Light expanded his role throughout all the ownership changes and rounds of layoffs, taking over business operations in addition to leading the newsroom. Soon-Shiong basically left him alone while he focused on his prized hometown newspaper. Sure, they felt like the ignored stepchild, but they’d carved out their own identity and nobody was messing with them.

As publisher, Light eventually created a plan to transition from a print newspaper to a modern publisher by 2030, able to support an editorial staff of 80 to 90 people with 100,000 digital subscribers. There are differing opinions on how realistic or creative of a plan that really was, but there was at least a plan.

Then came the sudden news: Soon-Shiong quietly made a deal with the one ownership group San Diego had managed to avoid in its 15 years of newspaper mayhem.

Just like that, the U-T was back in the American newspaper doom loop.

Alden — and its journalism subsidiary, MediaNews Group — have been tight-lipped so far in their plans for the newspaper. Regardless, it’s easy to fathom now what the U-T will look like under Alden. The staff will get smaller, much smaller. A U-T built around a digital subscription plan tries to preserve journalists and looks for ways to cut costs around them, like eliminating print days. A newspaper under Alden cuts journalists and makes sure a newspaper still lands on your doorstep, regardless of what’s inside it.

Employees estimate the newsroom has already been cut by around 30 percent. Light immediately left, as did many others responsible for that boom in quality.

What’s harder to conjure up is what happens after the big cuts. Unlike the private equity guys, hedge fund men don’t go for the quick sell. And anyways Alden is pretty much the only company buying medium-to-big newspaper companies now. After you hit the Alden era of ownership, there might just be no next step.

You just exist, in mediocrity or worse, as they drain out as many profits from the existing print product as possible and divert those profits to other investments. There’s no plan for the future. There’s certainly no digital transition. There’s just revenue extraction for as long as a generation of older newspaper subscribers live to keep paying their bills.

When they die, it’s fair to guess, the newspaper goes to the grave with them.

“They’ll skin it to the bone, and that will be the end of it,” said one worker still at the paper.

The suit jacket was off. His sleeves were rolled up, like he was ready to give them a heart-to-heart talk, as one participant recalled. Employees could submit questions ahead of time by email. But once he began, it seemed like he was reading from a script. When he sang the praises of the managing editor who was taking over in Light’s stead, Lora Cicalo, he pronounced her name wrong.

He also delivered employees an ultimatum: Alden would only be providing them information if they could trust employees not to leak it. “That felt crappy,” said one employee.

Today, more than three months after the sale, employees say they haven’t gotten much more detail than they did in those first days.

The buyouts have been staggered, so every now and again, they still get a goodbye email from another colleague. Internally, one newsroom worker said employees estimate that somewhere between 60 and 80 people are left from the 108-person newsroom under Soon-Shiong. Another said the mostly editorial staff meetings that used to have between 100 to120 people now feature 50 to 60.

If the newsroom is now at, say, 75 people, that would be just 18 percent of its 2006 size.

In other purchases, Alden has been known for quickly selling a newspaper’s real estate. Doug Manchester already played that move. Alden has instead bailed on the paper’s four floors of prime downtown office space.

In 2016, the company signed a 15-year, $40 million lease for 60,000 square feet of office space at 600 B St. The lease had a provision that allowed them to, for a hefty fee, get out of two of the floors in the seventh year. It’s unclear what’s going on with the other two floors; Alden can’t get out of those until 2026.

So, for the first time since the founders of the San Diego Union unloaded a printing press off a ship from San Francisco and set up shop in Old Town in 1868, the city’s newspaper doesn’t have a headquarters. All that’s left is The San Diego Union-Tribune logo, gracing the top of a downtown skyscraper until a crew gets up there to remove it. Employees now work remotely.

MediaNews Group executives didn’t respond to multiple interview requests for this story.

One thing they have told employees is that the U-T will be its own standalone company, not part of its larger conglomerate of Southern California media properties, which includes the Orange County Register and the L.A. Daily News. Newsroom employees are optimistic that will provide them with a degree of autonomy not afforded the other regional papers.

They’ve been told there will be no merit or annual raises; the only path to a pay bump is a promotion. The 4 percent company 401k match is gone, as is parental leave. Many are grateful to have jobs right now but are actively on the hunt for new ones.

They have the impression that Alden won’t be dictating what they write about. “The upside is they leave us alone,” one newsroom employee said. (We’ve granted anonymity to U-T employees so they can speak freely; in at least one case, an Alden reporter was fired after speaking to the media about the conditions at his paper.)

Nobody’s under the impression that things will be good. “In the few months since the sale, everything about the paper is different,” said one employee. “Way less staff. Everything is way busier. We don’t have as many reporters contributing to the daily reporting. There’s not a lot of clarity happening around what’s happening.”

The opinion page team has shrunk by half since the start of the year, from eight to four.

The U-T’s editorial page was long a major player of the daily conversation about San Diego public affairs. The editorial board exerted significant influence through its declarations and endorsements. Presidents and political candidates came to the editorial board’s conference room table to take questions. Now, there’s no table and there may never be endorsements again (Alden papers don’t endorse).

While previous editorial boards were establishment Republican, under Matt Hall the board was more centrist and less willing to identify a worldview. But it offered a robust mix of in-house editorials, outside opinion pieces from community members and conversations with political candidates. Now they’re just doing less. Hall is gone and Alden hasn’t named a replacement.

On the news side, people are just being asked to do more. Beats serve a distinct role for reporters: They allow you to build expertise and sourcing. People at the U-T now have so many beats that they sound more just like assignments than anything. This was a trend that had already begun before the Alden purchase, but has become almost farcical now.

Lauren Mapp already covered Indigenous communities and aging. Now, according to her X account, she’s also in charge of covering all the cities in East County. It’s hard to imagine a reporter being able to develop the kind of expertise and sourcing you need to do important journalism in that kind of structure. It’s more like a recipe for forcing someone to do a lot of stories, burning them out, getting them to quit and not replacing them.

In the aftermath the sudden sale to Alden, one of the nation’s biggest stories has unfolded on San Diego’s doorstep, as thousands of migrants have tried to cross into the United States daily, at a time when the nation’s asylum policy has been contradictory and confusing.

It was just the time when San Diegans needed Kate Morrissey, who’d carved out a reputation as an ambitious immigration reporter. In 2020, for example, she traveled to Nicaragua and Honduras to catalog bias and disparities and other failures in the asylum system.

Leading up to the buyout deadline, Morrissey had reported that border officials had been improperly refusing to take in asylum seekers, interviewed the new Border Patrol’s San Diego sector leader and detailed the conditions at the border as the Trump administration’s so-called “remain in Mexico” policy expired.

Morrissey, however, decided to take the buyout. “It is with a heavy heart that I share that I am among the SDUT folks leaving after the sale of the paper. My dedication to the mission, to the work, has not changed,” she wrote on X, formerly known as Twitter. “After much soul-searching, I decided it would be best for me to pursue that work through another org.”

Without Morrissey’s expertise and with a depleted newsroom, the paper instead turned to someone from its Guides Team to cover the crisis.

It was a long way from the typical assignment for the Guides Team. They usually offer recommendations about the best things in San Diego County: where to hike, read a book or try a vegan taco.

It will happen slowly, almost imperceptibly, over time. The print newspaper won’t go away. As a matter of fact, it will stay around even longer than it would have. It just won’t have much inside of it.

Dedicated reporters will keep working hard to bring you stories. They will just have to do more and more of them as their colleagues depart. They’ll have more beats until they’ll basically just be required to cover everything.

If the paper does have job openings, it will be hard to fill them with talented people. If they do ever have an office again, it won’t be a pleasant place to work — and could even be bad for workers’ health.

The Alden playbook is pretty clear: They buy distressed newspapers. They strip out and sell whatever assets they can of value, like real estate. They cut staff mercilessly until there’s a fat profit margin. They don’t invest those profits back into their newspapers. And they exist for as long as they can make money off of print advertising.

Though there’s been no formal announcement, it’s safe to say Light’s transition to digital is dead. In his Q-and-A a year before the sale, he had compared the U-T’s transition to one of Silicon Valley’s largest success stories.

“So will the U-T someday stop printing? Inevitably. Absolutely. You know, did Netflix stop sending out those DVDs to your house? Yeah,” he said.

Newspapers under Alden don’t aspire to be Netflix. They’re content to be Blockbuster, doing what they’ve always done until the last DVD players get sent to the electronics recycling plant.

And, in that metaphor, Alden’s Blockbusters don’t restock the shelves with new movies or big hits. The walls are mostly empty. There are a lot of B movies and sequels.

Of course, Alden could go in a completely different direction. But it has a clear playbook, and there’s little to suggest it’ll suddenly follow a different plan in San Diego.

Alden’s blueprint first became clear at the Denver Post. After another round of layoffs decimated staffing in 2018, staff there rebelled: The front-page of the Sunday opinion section declared that “Denver deserves a newspaper owner who supports its newsroom. If Alden isn’t willing to do good journalism here, it should sell The Post to owners who will.”

“The @denverpost is being murdered by its owners,” one Post reporter wrote on X. Alden hasn’t appeared moved by these kinds of uprisings; it continues to own the Denver Post.

In fact, Alden has kept buying. The hedge fund now runs the country’s second-largest newspaper chain — nearly 200 papers — and owns some of the most revered titles in the history of American daily journalism: the Chicago Tribune, Baltimore Sun, and San Jose Mercury News. And yes, every local newspaper owner is shedding jobs. But no one cuts quite like Alden: they’ve shed staff at twice the rate of its competitors, according to University of North Carolina research.

The stories are similar at Alden papers across the country. In the Bay Area, it cut a staff of 1,000 editorial employees at 16 regional papers by at least 85 percent. In Orange County, just four reporters were being asked to cover a region of 34 cities. In the Philadelphia suburbs, one reporter is in charge of election coverage for more than a dozen communities.

Doug Arthur is a research analyst who focuses on stocks in the media business. He summed up the Alden model simply: “They are the ultimate cash flow mercenary,” he told the Washington Post. “They want to find cash flow and bleed it to death.”

So where does that cash flow go? It goes to other hedge fund investments. Then there’s Alden’s founders, Randall Smith and Heath Freeman. The former bought a Miami mansion for $19 million in 2021; Smith recently sold his Palm Beach estate for $23 million.

The one thing you used to be able to say about Alden is they at least don’t tell journalists what to publish. But in early October the company told its newspapers to run an editorial urging the news media to refer to Hamas as a “terrorist organization.”

The editorial appeared in the print edition of the U-T. It did not, however, run online.

Instead, current and former employees direct their anger at the man who let the grim reaper in the door, Patrick Soon-Shiong.

The doctor often portrays himself as a savior. He is a man with missions: cure cancer, create a Covid vaccine and save local journalism. “It was like Christmas when he bought us,” said one employee.

The good vibes took a hit pretty quickly, when Soon-Shiong addressed the staff at the U-T shortly after the sale and compared them to abused children. And that made him a foster parent who was coming to save them. “It was very condescending,” Moran, the former U-T reporter, said.

That would be the doctor’s only staff address in his five years of ownership. After that, Soon-Shiong headed back to Los Angeles and, people in the newsroom said, didn’t pay much attention to the paper. The L.A. Times got splashy new investments in an effort to turn it around.

While the sale was sudden, the warning signs had been there. In 2021, the Wall Street Journal reported Soon-Shiong was exploring selling the newspapers. The doctor tweeted a rebuttal that was notable for its omission: “WSJ article inaccurate. We are committed to the @LATimes.”

Meantime, the investments at the L.A. Times fizzled out, and the paper underwent a round of layoffs earlier this year.

But the U-T was profitable, as Light had proclaimed to readers and staff. And that’s what makes people so upset about the sale. Why did Soon-Shiong, a billionaire who came in as a savior, need to offload so suddenly, and why to these guys?

To extend Soon-Shiong’s terrible metaphor from his first meeting some more, the foster parent snuck out in the middle of the night. Now San Diego, and its newspaper, are being cared for by journalism’s biggest deadbeat dad, and he’s spending their allowance on lottery tickets.

Philanthropist Malin Burnham wanted Doug Manchester to sell him the U-T at a discount, and let him turn it into a community-controlled nonprofit. They could preserve the institution, protect it from the financial pressures of being a profit generator, and the familiar newspaper name could continue to exist under a more community-based model.

Attorney Pat Shea was part of a group of financial heavyweights that Burnham assembled to evaluate whether they could make it happen.

“This was an enormously challenging event,” Shea said. “There were a million reasons why this couldn’t get done — and a few ways it could get done. He brought a lot of good energy. He was intent on making it happen.”

Bill Roper accompanied Burnham in meetings with a couple of major local philanthropists, but he said those donors were interested in funding things like education or medical research — not journalism. “We just did not find the right local billionaire tech guy who wanted to assist with the local paper,” Roper said. Still, Burnham remained convinced that he could raise the necessary funds to finance the purchase and operation of the paper.

But it never got that far. The team spent a year or so working on the various elements but Manchester eventually sold to the Tribune Company for a reported $85 million, ending their efforts, Shea said.

Under Soon-Shiong, the paper engaged in similar discussions with the San Diego Foundation and Arizona State University. It might seem like an odd pairing, but the ambitious university teaches students through real-world experience. A newspaper could be a hub for pro-am journalism, like a teaching hospital. The negotiations got serious enough that there were non-disclosure agreements signed, but it never came to fruition.

Moran wondered why Soon-Shiong, if he was so concerned about the survival of local news, couldn’t have gone back to someone like Burnham to give the nonprofit plan another shot.

There are no obvious signs that he did. Soon-Shiong didn’t respond to interview requests for this story. But that kind of model has increasingly shown promise since Burnham first explored it. In Philadelphia and Tampa Bay, the newspapers remain for-profit but are now owned by nonprofit companies, which eases the burden of profitability. The newspapers no longer need to be delivering profit margins to owners; that money can be reinvested.

In Salt Lake City, the Tribune went a step further, converting into a nonprofit organization entirely. It now brings in reader donations to fund its annual budget and its leaders have undertaken a digital transformation alongside the changes in the financial model.

Interestingly enough, the Salt Lake Tribune was once an Alden paper. They sold to a concerned local leader, Paul Huntsman, in 2016. He tried to make it work as a business but ultimately donated it as part of the nonprofit conversion.

But at this point it’s hard to imagine Alden selling.

In Baltimore, Stewart W. Bainum, Jr. tried. Hoping to avoid Alden ownership, the local hotel magnate made a play for the paper. He got so far with Alden that a sale was actually announced, only to be scuttled when, he says, Alden tried to add new fees at the end of the sale. When it failed, he threw his time and money into founding the nonprofit Baltimore Banner, which launched with a remarkable 42 journalists on staff and a $15 million budget.

If the U-T is stuck in Alden’s hands, a group of civic-minded philanthropists could decide to make a game-changing investment in a digital nonprofit newsroom like Voice of San Diego or inewsource that isn’t bound by such legacy business model problems. They each do public service journalism on modest budgets of under $3 million a year. Imagine what they could do with a Banner budget. Or a group could start its own newsroom like Bainum.

Any purchase of the U-T would’ve required raising many tens of millions of philanthropic money, if not $100 million.

The core mission behind that effort — to ensure that the region gets essential reporting and public and powerful institutions are held accountable — doesn’t need to die along with the U-T’s sale.

It would, however, require a fundamental shift in philanthropic thinking.

For decades, advertising created so much wealth that newspapers could support a vital public service and still make their owners rich. That’s no longer the case. Philanthropy will be a key way to fund the public service going forward, and San Diego knows how to fund things that way.

The San Diego Symphony Orchestra Association raised more than $70 million in grants and contributions in 2021. The Humane Society: $33 million. The Museum of Contemporary Art: $23 million.

The death of a city’s major journalism outfit isn’t a tragedy only if you’re one of those blessed souls who holds some deep reverence for the fourth estate. If you care about education, your schools just got less accountable and more opaque. If you care about local parks and beaches, the corruption of your local officials just got easier. If you care about democracy, your neighbors just became less likely to vote.

If you care about your neighbors, you’re about to know less about them, and have less in common with them — unless someone does something about it, soon.

Andrew Donohue is the investigative editor at CalMatters. He previously served as executive editor of projects at Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting and, before that, was editor of Voice of San Diego.

Andrew Donohue is the investigative editor at CalMatters. He previously served as executive editor of projects at Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting and, before that, was editor of Voice of San Diego.

This story was first published by Voice of San Diego. Sign up for VOSD’s newsletters here.