If you heard anything about the Miami startup Guide last year, it was likely that it wanted human- and animal-shaped digital avatars to read the news, creating video automatically from stories.

That vision is no more. (For video evidence of what that future would have looked like, check out the old Guide website.) “People would always say, This is so cool, This is awesome. The lesson is that cool and awesome doesn’t necessarily mean they need to stick around and keep using it.” says founder Freddie Laker. (Also, some people thought it was super creepy.)

But from its uncanny-valley ashes rises a (sort of) new kind of video news startup. “What we’re finding now with the new generation tech is people are saying, Wow, this is so useful, or Wow, this has changed the way I’m doing business.”

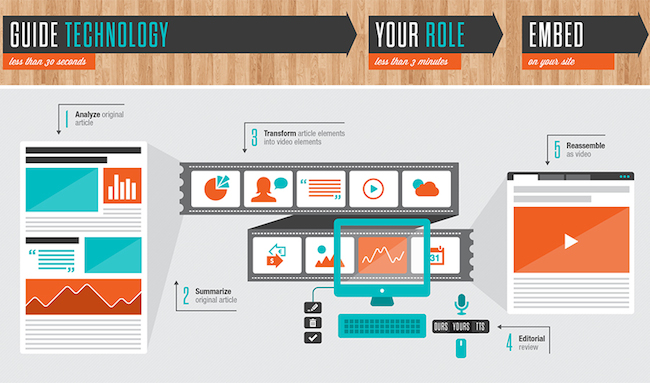

Guide is now a B2B automated video building service that helps publishers turn text articles into condensed, narrated video clips — minus the creepy avatars. The idea: Publishers can sell video advertising faster than they can actually produce videos. (See Joe Pompeo’s story today to read about The New York Times’ version of that dilemma.) But publishers are good at producing lots of text. If that text can be turned into videos people want to watch automatically (or at least quickly), it could open up new ad revenue.

With Guide, smaller publishers — those less likely to have connections with a video ad network or to sell video ads on their own — can choose a 50/50 revenue share for the videos they create for free. Guide says it has over 400 publishers signed up for that free program. Larger publishers, whose CPMs are considerably higher than what the Guide network can offer, pay five dollars to make a video, with a charge of $3 per each additional 500 video views. Laker says he’s in final talks with a few big outlets that might be interested in this program.

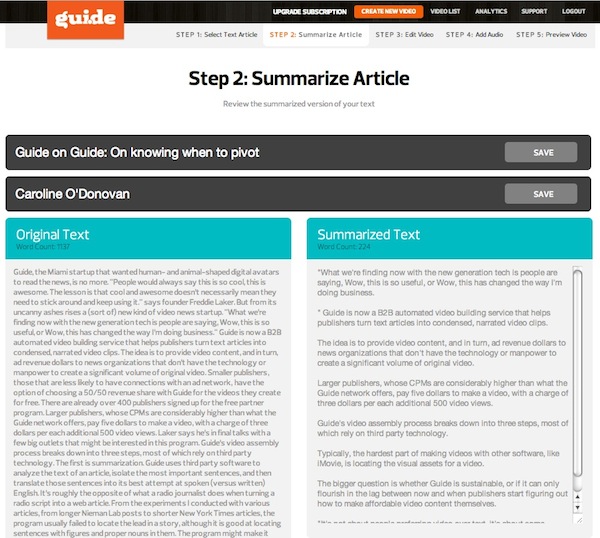

Guide’s video assembly process breaks down into a series of steps, most of which rely on other companies’ technology. After choosing an article, the first big step is summarization. Guide uses third-party software to analyze the text of an article, isolate what it thinks are the most important sentences, and then translate those sentences into its best attempt at spoken (versus written) English. It’s sort of a mishmash of Summly and the opposite of what a radio journalist does turning a radio script into a web article.

I tried using Guide with a number of different stories, from longer Nieman Lab posts to shorter New York Times articles, and the results were mixed. The program regularly failed to identify which sentence in the text would make the best logical opening line for a video; it was better at pulling out sentences with numbers and proper nouns in them. (Guide really likes numbers.) The program might make it easier for an editor unfamiliar with a story to summarize it and break it down into slides, but the actual author of a story could probably do the job faster on their own.

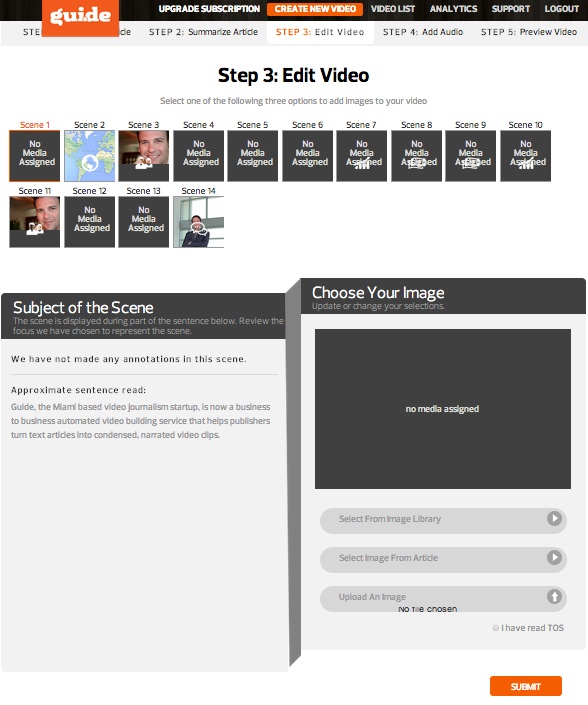

After the summarizing, it’s on to the visual phase. Guide measures the approximate length of the script when read aloud and auto-populates the appropriate number of slides. Using natural language processing based on Stanford’s CoreNLP project, Guide attempts to recognize newsy elements in a story— numbers, dates, locations, people’s names, companies — and inserts either a simple animation — a turning calendar pages, scrolling numbers — or an appropriate image.

“Whether it be additional images or extrapolating block quotes or numbers or currencies or locations or maps, pulling extra data for things like DBpedia to enhance the videos, I think we’re adding a lot of substance,” Laker says.

Typically, Laker argues, the hardest part of making videos with other software is locating the visual assets for a video. “The editing is the easy part,” says Laker. “That’s what’s time consuming, finding all the stuff.”

Though Laker says the program usually fills between 60 and 80 percent of the slides, in my test using an early version of this article, it managed to fill less than 30 percent. In experimenting with other stories, my results were about the same. And Laker is right — finding visual elements on my own was difficult and time-consuming, even with minimal effort.

In addition, the animations can be distracting or just beside the point: For example, in a sentence that delineates two sides of a conflict, a rolling ticker that counts from 1 to 2 is simply not illuminating. (For now, users are stuck with those animations, but a Guide representative said they are working on it.)

Once you’ve got a script and corresponding images, the final step is to find someone — or something — to narrate the video. The reporter or editor can make an original recording, or, for the top tier customer, at $20 a hit, a professional voice actor will record a reading of the article. But the truly innovative option, which is also facilitated by third-party software, is text-to-voice. Editors can choose from two American English female voices and one male voice, or a British female voice.

And with that, the video is ready to publish, and looks a little something like this. (We used a human narrator; Guide gives you two free credits to do so.)

Despite the bumps in the road, Laker’s ability to pivot and iterate should not be overlooked. “I started realizing, I raised all this money. I’ve got to do something, and I’ve got to do it quick,” he says of his decision in December to take whatever was left of his $1.5 million in seed funding and convert Guide from a consumer service to product-based company. (Some of that money came from the Knight Foundation, which has also provided funding to Nieman Lab.) At that time, he also realized he needed more feedback from publishers than he’d been getting.

“We’ve spoken to — without exaggerating — hundreds of editors and publishers across America, and actually a couple in Europe,” he says. “I would say on average, I speak to three to five publishers a week in a strictly interview format. Very strict no-selling rules, just learning.”

Laker has taken this lesson about feedback to heart. Guide is committed to updating every few weeks and, although the new site has some bugs, the team seems to be approaching them like so many Whack-a-Mole moles. For example, Laker says it will soon be possible to embed video files in a Guide video, which could improve production values considerably.

If one buys the idea that we’re headed toward increasingly automated video production, the bigger question is whether Guide is sustainable — or whether it can only flourish in the lag between now and when publishers start figuring out how to make affordable video content themselves. (There’s also the even bigger question: How much is the boom in video advertising CPMs supported by the fact that quality video production is hard? If suddenly we have 1,000× more quality video thanks to better automation, wouldn’t that send ad rates tumbling, just as happened with banner ads?)

Laker says the ever increasing demand for video content makes him confident about the space he’s playing in. “It’s not about people preferring video over text — it’s about some people preferring video over text,” he says. “Even if only 10 percent of people would rather watch a video summary, then this is very viable.” (Note that, in the Guide video above, the narrator has trouble catching the emphasis on the some in Laker’s quote; a robot would have fared even worse.)

But he’s not the only one that thinks so. Wibbitz is just one of the several companies that’s been working on perfecting the text-to-video transformation for longer than Guide. (The Wibbitz team, based in Tel Aviv, said they didn’t want to comment for this story.) Also experimenting with cheap, viral, mobile video is NowThis News, a company which recently received a major investment from NBC and which is betting on humans over algorithms. And, of course, there’s the ever bizarre but not-to-be-laughed-off Next Media Animation in Taiwan, and its corresponding partnership with Reuters. With so many ad dollars in video, it’s only going to get harder to stand out in this field.

Laker is smart to want to get into the readymade video business, but the question is whether the minimally-compelling-at-best content Guide currently produces will have a chance to make a mark in it.