As promised yesterday, here’s Part 1 of my interview with Jesse Thorn, the host of public radio’s The Sound of Young America. (Or perhaps it’s more accurate to say “The Sound of Young America podcast,” given what Jesse says below about his interactions with both the public radio mainstream and his devoted core audience online.) Here we talk about the show’s philosophy, how his audiences guide his choices, and how he supports himself. Among the topics we cover:

— How having a show on dozens of public radio stations can still only generate about $10,000 a year;

— How showing your mistakes can build listener loyalty;

— How a truly dedicated audience can turn into a business model; and

— How an NPR voice can get you a beautiful wife.

You can listen to it by pressing play in the audio player below, or by downloading the MP3 directly here.

[audio:http://www.niemanlab.org/audio/jessethorn1.mp3]

There’s also a full transcript below.

Josh: For folks who might be unfamiliar with your show, how would you describe The Sound of Young America?

Jesse: Well, the log line is a public show about things that are awesome. So basically if you imagine Fresh Air, and then take out all of the boring parts, and…no, there are no boring parts on Fresh Air, which is one of the best radio shows in the world. But if you take out all the parts about, like, the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, and then put in interviews with rappers and comedians and rock and roll guys — that’s pretty much The Sound of Young America.

Also, you should maybe remove like, maybe 25 percent of that kind of weird public-radio dispassionate disconnection in interviews. Like, maybe I might actually engage my guests a little bit personally.

Josh: Right.

Jesse: Or make a joke. So, yeah, it’s sort of like Fresh Air, 25 percent less dispassionate disconnection, a lot more rappers, significantly more comedians, and some rock and roll guys.

Josh: I imagine that the unique set up of your show gives you complete control over your guest list. It seems that you tend to have people who you feel a bit more of a passionate appreciation for than for a show that might be also programmed based on what’s the news of the day or what is — who’s on book tour or having to connect with the culture at large. Yours seems more self-directed.

Jesse: Yeah, I mean, part of that is — I think you’re very correct in making that assertion. Part of it is that outside of my intern Brian, who is sitting behind me right right now putting t-shirts in mailers, it’s pretty much a one-man operation and has been for quite some time.

And it’s a very personal program. I think the strength of The Sound of Young America is my personal editorial perspective. So I pick the guests that come on the program, based on my own personal taste, interest, and cultural knowledge. Sort of in the same way that Flavor Pill tells you what party to go to on Friday night, or what club night is the hot club night that night. I try to point you towards what’s a cool thing.

That’s largely just because I did the show basically for free for the first five years or so and still barely make anything. When you’re doing that, it’s a lot easier to get yourself excited about working for free, interviewing someone that’s like totally your hero or you think is totally awesome, than it is to get yourself geared up to interview someone for free about civic responsibility or something like that.

Josh: Right. I’m curious how you feel that approach changes the connection that your audience has with the show. In writing endeavors and blogging and other things, I think when people can see an identifiable personality behind a journalist writing — as opposed to the voiceless newspaper style — that they feel a stronger connection, and they feel a more of devotion to the show. Even if that personality that the writer is having might not complete the one-to-one match up with the readers, just as your sensibility might not completely match up with your audience’s. Does it increase that connection?

Jesse: Undoubtedly. It’s a self-conscious choice. When you’re doing something that’s supported by donations — you know, my livelihood is completely dependent upon people feeling, like, more than a utilitarian connection to what I’m doing. You know, if people — I think as many people as listen to like Morning Edition or something like that, or watch Dateline — is that a show? Dateline NBC?

Josh: Yes. That’s the predator show, yeah.

Jesse: Yeah, you know — they have enough connection to it to watch it, but whether they would have enough connection to it to willingly donate money to support it is an open question. So when you’re doing something that’s on the kind of scale that I’m doing it and so on, having that sort of connection — it’s why I’m on Twitter and I participate on my forums and I blog. And I do another show called Jordan Jesse Go!, which is much more sort of personally oriented.

I was just talking with somebody yesterday. I was talking with the comedian Todd Glass, who does a podcast called Comedy and Everything Else. He’s a really brilliant comedian, but when he started this podcast it was his first outing in this kind of broadcasting mode. He was saying: What do you do with your really old episodes? Do you bury them? Did it take you a long time to figure out what you were doing? And I said: Yes, frankly it did take me a long time to figure out what I was doing. But we actually podcast our old episodes, at least the ones that we have recordings of, from when we were in college seven years ago just because some of our big fans really like that and they’re like really into seeing how the show developed and stuff. So even though it’s a little bit embarrassing, anything that I can do to make a more profound connection with the audience is — I kind of see that as being my job. That’s what pays my bills.

Josh: It’s difficult to think of a newspaper city-hall reporter inspiring that kind of completist approach — like, “I want to get his early EP when he didn’t know what he was doing, that early city council meeting he covered where he screwed up the mayor’s name.”

Jesse: Yeah, but you know there are people like that. In San Francisco, there are a couple of city columnists, Matier and Ross, who would only mean something to San Franciscans, but they’ve been writing the Chronicle for many years and they also do several other multi-media endeavors on radio and TV in the Bay area. They have a very strong editorial voice, even though they’re basically doing a local news scoops dot-dot-dot column. But you know, it’s not completely incompatible.

Josh: Yeah. So tell me about your history of interactions with the public radio mainstream. Your show is on a couple dozen radio stations. It seemed from your list that they all happened to be in Vermont for some reason. But when you started this show back in college and you thought, okay, this might be something I want to do for a living — how has your dance with public radio been?

Jesse: Well, you know, I started the show before the Internet was a viable way to transmit rich media, for the most part. It was like 2000 when I started the show, so — you know, I guess I could have done something in like Shockwave or something like that. But basically, my idea when I started the show was it was really cool that you could have your own radio show! And sort of quickly became: Well, maybe someday I could have my own radio show professionally. Because of the dire landscape of commercial radio, I pretty much keyed in on public radio early on.

So the history of the show is sort of like — it started as my college radio show with my buddies Jordan [Morris] and Gene [O’Neill], and we started doing a lot of comedy and original stuff, realized that was too much work, so we started including a lot of interviews which are a much easier way to fill time when you’re a full-time student and you have to program an hour a week.

So we did that for a long time. Eventually Jordan and Gene graduated, I started doing the show by myself and it really became an interview show then, because I was terrified of trying to host a call-in talk show, which is a very challenging endeavor.

So then after I graduated, I continued to do the show at the same college radio station I had done it before. I was driving back and forth between San Francisco where I was living and Santa Cruz where I went to college, which was like an hour and a half drive.

About three and a half years ago, or something like that, I heard from the NPR station in Santa Cruz, KUSP — apparently there was somebody on their board who listened to the college radio station sometimes and had heard my show. He told the program director, hey, there’s this really cool show on the college radio station — maybe you should think about bringing it into your schedule.

And right around that same time which was sort of the very beginning of podcasting, I started podcasting. Basically the reason I started podcasting was I figured if 80 people would listen to me, that seemed worth a couple of hours of work. It wasn’t that much work to make it into a podcast from already being a radio show. Then eventually Apple launched podcasting support in iTunes, and my audience went from 200ish to 2,000ish and then it really seemed worth it to do a podcast.

I kind of went along, deedle, deedle, doo, and eventually Public Radio International contacted me. At that point, I had a couple of affiliates, but they were like tiny college radio stations that I had contacted myself and offered the show for free. PRI contacted me because public radio was trying to have more sort of younger-person-oriented shows. We did a big dance for a really long time around it and eventually they picked up the show, right around the time that WNYC in New York picked up my show for a trial run. And after PRI picked up my show, WNYC decided to make my show permanent and I’ve added affiliates along the way.

Public radio operates like public television, on a very locally controlled basis. So, you really have to convince one program director at a time. It’s been quite a challenge. The reason I have so many stations in Vermont is because Vermont Public Radio added me. I just added a bunch of stations in New Jersey because New Jersey Public Radio just added me.

It’s really station-to-station baseball, trying to get stations to pick up your…wow, that was a really complicated mixed metaphor, radio stations, station-to-station baseball. It’s a long row to hoe, getting stations to pick up the show.

So, at this point, to be frank — I go back and forth. But at this point, I’ve almost checked out of trying to get radio stations to pick up my show. Just at this moment — this may be different tomorrow, or next week, but at this point, I’m kind of feeling like if they do, they do, and if they don’t, they don’t.

Frankly, most of my income comes from other sources besides public radio. Even if you are on 20 or 30 public radio stations, you don’t get a lot of money out of them. So, maybe my time is better spent making my show better than it is convincing a 58-year-old guy in triple-pleated khakis that my show about interviewing comedians and what not is worth their airtime.

Josh: Not to mention rappers. The rappers are probably the scariest part.

Jesse: Yes, the rappers are a big one. Frankly, rappers are so hard to get to show up. As much as I love hip hop — it’s my favorite kind of music, I love it, I always have loved it — I don’t have as many rappers on the show as I’d like to.

Josh: So, do you have a read on what percentage of your audience is listening through the podcast versus through radio?

Jesse: You know, I am on a couple of big public radio stations, God bless them. WNYC in New York and WHYY in Philadelphia, which are two of the biggest public radio stations in the country. I’m also on some mid-sized public radio — I’m in some mid-sized markets on public radio stations as well, like KUSP in Santa Cruz — the Monterey Bay area is actually a pretty big market, a couple of million people. I’m in Salt Lake City and that kind of thing. New Jersey’s no joke either.

Just by virtue of being on those stations, I think my audience is a lot bigger on the radio than it is on the podcast, frankly. I think it’s probably 75-80 percent on the radio. A lot of public radio stations run 12 repeats of Garrison Keillor every weekend. And if you throw up a repeat of just about anything on WNYC, and you have a reasonable time slot, 30,000 people are going to listen.

Josh: Yes. How many podcasts subscribers or listeners do you have?

Jesse: For The Sound of Young America, we’re hovering around a quarter-million downloads a month, which is obviously spread out over this big archive that we have. The downloads of a given show depends on the show, obviously, but if you discount the people who download on a one-time basis, sort of as best as you can, I’d guess that the actual subscriber base — like the people who are not only subscribed, but also download and check in on their podcasts a couple of times a week, and download a new show every time there is one — 12,000, 13,000, something like that right now.

Josh: I subscribe just to the RSS feed of your blog, and play things when you post them there. I don’t subscribe to the podcasts in iTunes or anything. It’s difficult to keep track of the various ways of getting to your stuff.

Jesse: The vast majority are from iTunes — about 95 percent of my podcast downloads are from iTunes. And I think it’s about 80 percent of my total downloads are from the podcasts rather then from the web. People don’t really like listening to audio on the web, frankly. So, the podcast is the most convenient way for people to listen, for the most part.

Josh: I started hearing about your show on MetaFilter, and other similar sorts of blogs a few years ago, and the conception I have of your show is as a podcast — as opposed to as a radio show, just because that’s the way that I approached it. Is your self-conception one or the other? Do you think of yourself primarily as a podcaster, as a radio host?

Jesse: It depends on the context. I mean I definitely think of myself as a podcaster much more than any other radio host I know. Whether I think of myself exclusively as a podcaster — no, I mean, I try and embody sort of the positive values of being on the radio, and especially public radio, which is a sort of, you know — a kind of high-mindedness or aspiration to quality and dedication to making something really good that is not always reflected in the world of podcasting, frankly. I mean, it is sometimes, often, but not always.

But on the other hand, if something comes down to it and I have to decide — if there was ever a sort of Sophie’s Choice, radio host or podcaster, I guess I would probably end up picking podcaster, just because, you know, that audience is my audience — you know what I mean? Those people are there to listen to my show. It’s not just somebody who happens to be going to pick up their kids and they always have their radio tuned to the public radio station. Those are people — the people who listen to my podcast are people who chose my show, and they — that audience is what sustains me financially, and that audience is — they’re the ones who send me emails and post on my forums and all that kind of stuff. So, ultimately if I had to pick it would probably, frankly, be podcaster.

Josh: I guess we’ll have to see what you put on your tax form every year.

Jesse: Well at parties I definitely tell people public radio host, because I do not want to get involved in explaining what a podcast is at parties.

Josh: Yeah, that’s how you get the action at the parties. You start saying you’re a public radio host.

Jesse: Hey, you know Andy Bowers, long-time NPR correspondent — he was the Washington correspondent, the Moscow correspondent for a really long time. Now he works for Slate. He’s a friend of mine and I found out that he met his wife — who is quite beautiful, by the way — at a party where she recognized his voice from NPR. So it can happen.

Josh: Yes. Gentlemen out there, invest in voice training.

Jesse: You got it!

Josh: Let’s talk about the financial end of things to the degree you feel comfortable doing that.

Jesse: Sure.

Josh: You mentioned the donations that you get from your audience. Is that the majority of the money you generate from the show?

Jesse: I’m trying to think if it’s literally the majority. I think it’s — I think it is. I think it’s a little more than half. I’m sort of doing the math off the top of my head right now. But yeah, it’s a little more than half, and about a quarter comes from underwriting — which is actually MetaFilter you mentioned. He, MetaFilter supports the show financially too. And then sort of like a smaller portion — let’s call it — comes from public radio stations. I think — I did my taxes recently. I think the amount I got from public radio stations was — I don’t think there’s any reason I’m not allowed to say this — it was like $10,000 dollars last year.

Josh: Wow, for being on a couple dozen radio stations?

Jesse: Yeah, right! But you know, what’s amazing about it is if I wasn’t with PRI, I wouldn’t be able to get anything. When WNYC ran my show before I was with PRI, they gave me some money, but only out of the kindness of their hearts, because they were trying to look out for me. Generally speaking, if you’re not with PRI, American Public Media, or NPR, you don’t get anything for your public radio show from stations.

Josh: Now we’re going to talk about MaxFunCon a little bit later, but have you thought any about expanding your brand into other products or projects? I mean, is there a book to come that could come out of the show, or is there something else that might make sense?

Jesse: Yeah, well, I made a television pilot this past year and was really happy with it. It didn’t end up going, basically because the network that I made it for changed the structure of their programming right before we finished, in such a way that the structure that we had used for the pilot was no longer compatible with what they were doing. But that was a really fun thing to do.

Whether I’ll write a book, I get a lot of solicitations from publishers and publishing agents. Writing a book is really complicated and hard, and at this particular second, I don’t know if I have a really compelling book to write. And I wouldn’t want to write a book that was lousy just to kind of cash in on my very very marginal marginal marginal fame. But that’s always a possibility.

I mean, there’s lots of places where — there’s lots of opportunities that are starting to come up, you know. I’ve been meeting with agents and managers lately. I think I’m gonna get me one of them. You know, people got those.

You know, the other day a listener, who’s also a famous public radio producer, dropped me a line and said: Hey, would you be interested in being the voice of X in X major major major major brand for a national radio campaign my friend is producing? I said yes, and it didn’t end up working out at the last minute, but — you know, if I had gotten it, it would have been roughly two days of work and would have represented 15 or 20 percent of my net income for the year. So, you know, there’s opportunities.

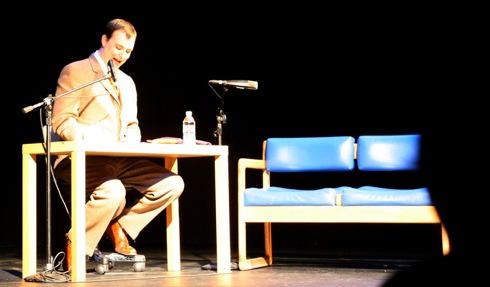

Photo by Nicole Lee used under a Creative Commons license.