The Awl put it best: “For sale: Perennial runner-up weekly publication in dying media segment. $0 or best offer. Includes funny Tumblr.”

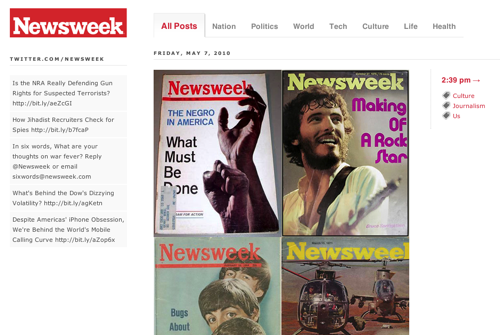

The Tumblr in question? Newsweek’s. Yes, Newsweek‘s. The “foul-mouthed” and “Gawkeresque (old Gawkeresque)” cousin of newsweek.com — the site that, in response to this week’s news of the magazine’s sale, announced: “Look, We Don’t Want to Seem Ungrateful, But if We Are to Be Acquired by Any Latin Superstar, We Kinda Hope It’s Shakira”…tagging the post “Culture,” “Journalism,” “Us,” and “Our Hips Are Exceptionally Truthful.”

Like the best Tumblrs, the site is random and trenchant and funny and unapologetically idiosyncratic. But what’s most striking about it, for our purposes, is that the Tumblr is all those things…while also being very much a vehicle of “the Newsweek brand.” It’s not just that the bright-red Newsweek logo is the first thing that catches your eye when you visit the site; it’s also that, more significantly, much of the Tumblr’s content is curated from Newsweek’s primary web offerings. Yesterday, it reposted this pearl of wisdom from a comment on the parent site (with the note that “sometimes the Newsweek commenters just crack us up”): “About ten years ago I heard someone from the homosexual lobby say that the only music genre they had not infiltrated was country music! Immediately after that Leann Rhimes did a duet with Elton John and now, here we are.”

Indeed. While “the Tumblr and its sense of humor and things like that are probably slightly different from the general Newsweek audience,” acknowledges Mark Coatney, Newsweek.com’s projects editor and the Tumblr’s creator and producer…it’s not that far afield. Today, for example, the Tumblr features long(-ish) excerpts from Newsweek pieces about the Palin/Fiorina endorsement and the outcome of the British election. “I feel like I have a pretty good idea, organizationally, of what the Newsweek sensibility is,” Coatney told me. “That might be slightly different from mine, but I try to hew closely to that.”

When traditional media latch on to new forms

The Tumblr’s fate is, at the moment, as precarious as that of its parent magazine. But it’s worth noting that, even as Newsweek, as a magazine and a website, got a reputation for mediocrity and stagnancy — and even as, yesterday, all the familiar they failed to innovate truisms came out in full, schadenfreudic force — over at the outlet’s Tumblr, innovation (and experimentation, and engagement and conversation) were actually taking place. Just on a small scale.

“The nice thing about management is that they’ve been very much like, ‘Experiment. Do whatever you want. Don’t embarrass us too much. And see how it goes,'” Coatney says. The institution gave agency to one of its members to experiment with something he cared about; it gave him leave not only to leverage his expertise, but also simply to have fun as he leveraged. The groking and the rocking, rolled into one.

Which is a small thing, but a rather profound one, as well. “The problem with the magazine industry,” Evan Gotlib wrote (in a post quoted on, yes, the Newsweek Tumblr), “is that they all too often latch on to new technology (Let’s make an iPhone app! Let’s build a Facebook fan page! Let’s create print ads with RFID scan technology! Let’s start a Tumblr blog!) without understanding the REASON behind that beautiful technology. It’s not a strategy; it’s a last gasp tactic.” The secret sauce of the Newsweek Tumblr, though, is the fact that it wasn’t part of a strategy at all. It was simply an experiment, given the freedom (from commercial pressure, from corporate overlordism) to develop organically. As Coatney puts it: “It was kind of nice not to have any expectations around it.”

Another way to put it: the Tumblr, as part of an overall approach to institutional media, suggests the power of the personal — the idiosyncratic, the unique — in journalism. The site is aware of the institution whose brand it bears, but isn’t overwhelmed by it. On the contrary: The Tumblr has “made us able to put our story out there and talk to people in a way that I think is hard for big media companies to do,” Coatney says. But it’s flattened the conversation, putting Newsweek — the Media Institution — and its readers on equal footing. And it’s made the Media Institution more responsive to its users. The Tumblr — and, in particular, the ability to see what posts people comment on, reblog, etc. — “gives me a good sense of what people respond to,” Coatney points out. So “you get that immediate feedback.”

The problem of scale

Which isn’t to say there aren’t tensions between the personal and institutional in even something as unassuming as a Tumblr. Scalability can be a challenge, for one thing. In the same way that a Twitter feed with 1,000 followers will have, almost de facto, a different voice than a Twitter feed with 100,000 followers, a Tumblr that gets too big — Newsweek’s has about 8,000 followers right now — could lose its power, and its voice, and its quirk. “It’s a real concern of mine,” Coatney says. “Because part of the value of this is that you’re able to talk and respond to and reblog people. If I see something that I like from somebody else, I try to comment on it and point it out. And if suddenly there are a million people talking all at once, I’m not sure quite how to deal with that yet.” (Then again: “If we get a million followers, I’ll happily try to figure that out.”)

Another challenge is the perennial one: commercial appeal. The Tumblr, on its own, isn’t easily monetized through online ads or other traditional methods of money-making. Right now, the site gets about 1,000 visits a day, Coatney notes — “not really a volume in which many advertisers are going to be interested.”

Still, from the branding perspective, the Tumblr represents a mindset that is scalable. Whatever Newsweek’s fate — and whatever responsibility it must take for that fate — the outlet currently has an example of innovative thinking under its institutional umbrella, one that serves as a reminder of what the best journalism has always understood: that there’s nothing wrong with a little whimsy. “In the end, we use Tumblr not because it’s a great way to connect with our readers (though it is that), or because we believe this or something like it is a part of a new way forward for interaction between publishers and audience (though we think that too),” Coatney writes. “We use Tumblr because it’s fun and while, you know, you can’t eat fun, or trade it in for fistfuls of dollars to fund serious journalism, we believe there’s a value in doing things we like simply because we like to do them, and that hopefully our fellow Tumblrs will too.”