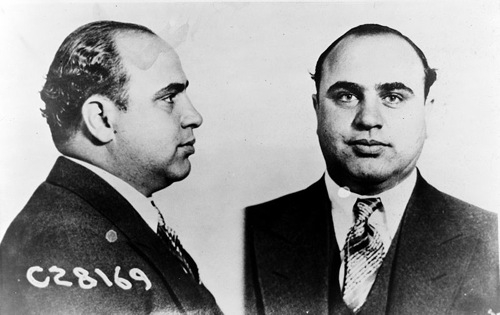

What should a good government organization with an investigative bent look like in 2010? That’s the question leaders of the Better Government Association, a Chicago institution that’s been battling city corruption since Al Capone, have been asking recently. The BGA is best known for its investigative partnerships with Chicago media, perhaps most famously the time it helped the Chicago Sun Times open and operate a bar called The Mirage Tavern. The 1977 investigation documented rampant city corruption, from kickbacks to tax skimming.

That type of investigative work is needed now more than ever, the BGA’s new executive director, Andy Shaw, told me. Shaw pointed to a combination of serious problems in city and state government (e.g. Rod Blagojevich) and the decline in the power of the state’s biggest traditional media outlets (e.g. the Chicago Tribune’s parent company currently being in bankruptcy proceedings). How does an institution like the BGA have impact in that kind of an environment?

Shaw, a veteran politics reporter for the ABC affiliate in Chicago, joined the BGA in June 2009. Since then, he’s quadrupled the BGA’s budget to $1.5 million, thanks to a number of foundation grants from places like the Knight Foundation and charitable arms of companies like Boeing. He’s ramped up the operation from a staff of two to a staff of 14. Shaw just announced the hire of three veteran Chicago reporters: Bob Reed, Bob Herguth and John Conroy (recently profiled in CJR). And he’s rethought how the BGA should operate in a new media age.

“All of this is made possible by the realization that we have a service that is critically necessary,” Shaw told me. “We know how to investigate.”

I spoke with Shaw about his specific plans for expansion. He was candid in his responses, saying he hopes other cities will start up their own BGA-style organizations — not unlike the boom we’ve seen recently in regional investigative nonprofits. “We’re trying to create a model for anti-corruption watchdogs to operate,” he told me. “There’s this desperate need for information and scrutiny.” Here are a few of the areas where the BGA is investing.

The rest of the journalism world seems to be catching up to the BGA when it comes to partnerships between nonprofits and news organizations. Shaw says now’s the time for BGA to diversify the kinds of partnerships it has. The group will still maintain relationships with traditional outlets like the Chicago Sun-Times and local television stations, but they’re also looking to online and niche publications, like Crain’s Chicago Business, and the education-focused Catalyst Chicago. One of its strongest partners is the Chicago News Cooperative, which provides The New York Times with content.

“The lifelong mission of this organization, which goes back to 1923, has become increasingly more important as legacy media is less able to do its old job,” Shaw said. “We have had an increasing number of partnerships with media in the pursuit of good stories. Over the last year, we’ve doubled the number of partnerships.”

Traditionally, the BGA reached an audience through its partner news organizations. Thanks to a grant from the McCormick Foundation, Shaw says they’re in the midst of a major overhaul of their site, which will begin rolling out in October. The site itself will become a destination for information, plus a place for users to submit content or tipsters to reach investigators.

“They’ll be able to report problems with government, ranging from potholes that don’t get fixed to snow that doesn’t get removed, to work sites where nothing gets done, to boards, commissions and agencies that don’t seem to be doing their jobs — or doing their jobs in a questionable way.”

BGA also wants to train locals to do reporting themselves, letting users contribute blog posts to the site. Shaw hopes that distributed effort will allow BGA to move into parts of Illinois outside Chicago. Their Watchdog program offers in-person training on filing Freedom of Information requests and other investigative basics.

Shaw is clear that BGA is an advocacy group, with a mission to stamp out corruption. That means a great story with no impact is of less value to BGA than it might be to a news organization. He wants readers contacting officials and pushing for change. “The biggest difference is we’ve begun to understand how important civic engagement is,” he said. “It’s not enough to disclose. We must propose solutions. Everything we uncover is matched with a source of remediation: cancel the contract; rebid the contract; revisit the salary structures. We are telling the subjects of our stories what we think they ought to be doing.”

Though BGA brings an advocate’s perspective, Shaw’s effort to double down on impact is right in line with what other nonprofit news organizations are facing. Nonprofit news organizations like the Center for Public Integrity and ProPublica all talk about impact as an important part of their viability as nonprofits — results sell better to funders than stories alone.