For the past two days, Italian Wikipedia replaced its site’s standard content with a message:

Dear reader,

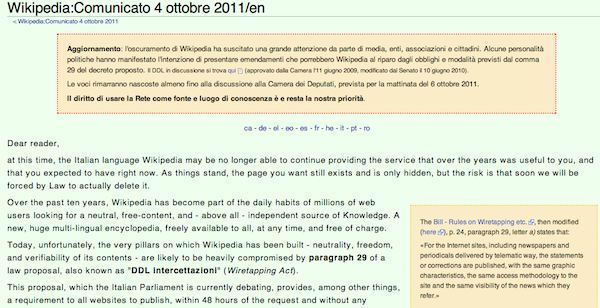

at this time, the Italian language Wikipedia may be no longer able to continue providing the service that over the years was useful to you, and that you expected to have right now. As things stand, the page you want still exists and is only hidden, but the risk is that soon we will be forced by Law to actually delete it.

As the message continued, it became a manifesto: The Italian Wikipedia website had gone (voluntarily) dark as a protest against DDL intercettazioni, an anti-wiretapping bill being proposed in Italy’s Parliament. The law (its title loosely translates to “Wiretapping Bill”) is apparently a reaction to recent wiretapping escapades that have caused trouble for, among other Italian officials, prime minister Silvio Berlusconi — who’s been caught both dismissing Italy as “a shit country” and making some rather crass comments about Angela Merkel.

The bill’s most contentious section is paragraph 29, which stipulates that, should any blogger publish information deemed to be defamatory — deemed to be so not by a process of judicial review, but by the subject of the alleged defamation — then the blogger will be forced to print a correction within 48 hours of publishing the offending post. Or else pay a fine of €12,000 (nearly $16,000).

Arbitrary/reckless/dangerous/ridiculous/a further blow to press freedom in Italy — insert your preferred objection here.

The outrage over the proposed law has been brewing for a while now, but it gained force this week, as the bill’s being debated in the Italian Parliament. And Wikipedia’s blackout of all its entries in Italian — around 800,000 of them — brought the protests to a head. The Wikimedia Foundation itself voiced its support for the protest, couching its argument in the idea that Wikipedia is self-policing, and therefore beyond the auspices of government regulation:

The Wikimedia Foundation stands with our volunteers in Italy who are challenging the recently drafted “DDL intercettazioni” (or Wiretapping Bill) bill in Italy. This bill would hinder the work of projects like Wikipedia: open, volunteer-driven, and collaborative spaces dedicated to sharing high-quality knowledge, not to mention the ability for all users of the internet to engage in democratic, free speech opportunities.

Wikipedians the world over pride themselves on their ability to rapidly remove false information from their project. Wikipedia has established methods to receive complaints or concerns from individuals or organizations and a strong system exists to remove incorrect or false information, and if necessary to remove complete articles in an effort to prevent vandalism. For Wikipedians, there is no value nor need for this proposed legislation.

Jimmy Wales put it more bluntly: “Wikipedia Italy is on strike against an idiotic proposed law.”

As Wales explained to Chris Potter, the Perugia-based director of the International Journalism Festival, “Italy already has perfectly fine laws against defamation, and this proposed law overreaches dramatically. I have never heard of any law like it anywhere else in the world.” The decision for this week’s blackout, he continued, “was taken by the Italian community in part because they felt that there was no genuine avenue for protest in the mainstream media without a bold action.”

And it looks like the protest may have worked — sort of. Yesterday, the Italian government announced that it will be modifying the proposed law to include only large online news sites — meaning that any information outlets that don’t fall into that category, Wikipedia among them, will be excluded from the law’s reach.

So: good news? The hashtag #graziewikipedia, which popped up in response to the development, would suggest so. But while the update, and today’s return to a blackout-free site, may represent a superficial victory for Wikipedia — and a nod to the encyclopedia’s network-effects-rooted power as, yep, a political lobbying force — the bill still holds. And the episode overall is a good reminder of the generally dismal status of press freedom in Italy. Berlusconi owns the influential private media company Mediaset; he exercises direct control over state television. Italy’s 100,000 professional journalists, to get work, must belong to the Ordine dei Giornalisti — a group that is, in effect, a modern-day guild. This year’s Freedom House survey of global press freedom, citing “heavy media concentration and official interference in state-owned outlets,” ranked Italy as only “partly free.”

It’s a worrisome state of affairs — one that Italian journalists are both keenly aware of and, as the DDL intercettazioni episode suggests, largely powerless to fight. As La Repubblica’s Vittorio Zambardino, the paper’s “Scene Digitali” blogger, told me when I met him in Perugia last year, over-regulation of journalism and the online space is a constant threat in Italy. And, for that matter, in Europe (and elsewhere) more broadly. “There’s a wide array of social processes that are produced by the Internet that are also endangering the virtue and the value of the Internet,” Zambardino said. He continued:

Freedom is going to be killed by strict regulation taken by governments. In Italy, we are very worried about this. But it’s not only Italy: the European Union has very strict views about privacy, about anonymity, about what they call “the freedom of the Internet.” In an ironic way — because they don’t believe in the freedom of the Internet.