Scott Detrow heard a rumor, and like any good reporter, he set out to determine whether it was true. Detrow, who has spent several years covering state politics and government for seven public radio member stations in Pennsylvania, had been told anecdotal claims that the expansion of drilling wells in recent years has drastically increased the burden on emergency service providers in the state. But the drilling industry, which opened 4,000 new wells in 2009 alone, is a controversial topic in Pennsylvania, and Detrow said both the opponents and proponents rarely agree on even the most basic facts.

“I figured 911 records were a good place to take a look at that,” he told me in a recent phone interview. “So we got the 911 totals from the 10 counties with the most drilling and we saw seven of them did, in fact, see their numbers go up. And we did that as a framework to get into what that meant in a couple communities.”

“We had to focus on what story we were trying to tell.”

The end result was a two-part story. In the first, Detrow reported that 911 calls spiked by at least 46 percent in one of the counties after the introduction of new wells. “We’re seeing more accidents involving large rigs,” the head of one 911 call center told the reporter. “Tractor trailers, dump trucks. Vehicles — tractor trailers hauling hazardous materials. Those are things, two years ago, that we weren’t dealing with on a daily basis.” In the second piece, Detrow explored the impact the increased burden on emergency services had on local county governments, many of which were having a hard time finding the funds to hire new EMS employees. “[County Commissioner Mark] Hamilton, who serves as the president of the County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania, supports an impact fee on gas drillers to help offset the cost of more resources,” Detrow wrote.

Compiling all this data took extensive man hours, and it paid off; Detrow managed to break a major story that settled a contentious dispute. But if he had tried to hunt down the data just a few months before, he would have run into a significant barrier: time. That’s because, up until recently, the reporter had spent the majority of his work week reporting on lawmaking in the state’s capitol building. “[Drilling] is something I’ve been covering over the last few years and it’s something that’s steadily become more of a main issue that I was spending more time on, but I was doing so through the framework of multiple stories a day on my beat and also having to cover everything else in state government.” Much of his reporting involved simply recounting what lawmakers were saying — and there were few opportunities to dive deeper into longer-term issues.

In late June, though, Detrow joined NPR’s StateImpact. Billed as “station-based journalism covering the effect of government actions within every state,” StateImpact essentially takes the extensive resources of a national news organization and applies them to the local level. For its initial iteration, NPR member stations from around the country sent in applications, and from those eight were chosen to receive grants. The grants, in part, funded the hiring of two reporters for each state: one for broadcast and another for the web. NPR also hired a team of project managers, designers, and programmers to work at its D.C. headquarters; this team collaborates directly with each of the participating states to create platforms and other tools to mine deeper into a given topic. Because every state differs in its most important issues, each participating team focuses on a particular topic. The Pennsylvania StateImpact reporters, as you may have guessed, focus on energy, with a concentration on the impact of drilling. Three of the states (Florida, Indiana, and Ohio) cover education while the remaining ones (Idaho, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and Texas) report on issues ranging from the local economy to state budgets.

“Why don’t we work together so we can get something that’s easy for us to use but also know it’s going to be accurate?”

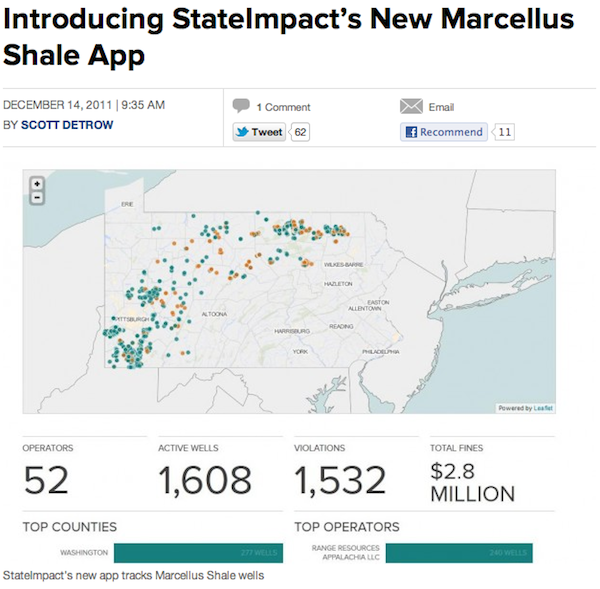

To understand what the D.C.-based team brings to the equation, I visited them one morning at NPR’s headquarters. They started off the day with a meeting in which each member listed off his or her task for the week. In order to ensure the meeting didn’t stretch any longer than absolutely necessary, they all conducted it while standing. Afterward, I sat down with Matt Stiles, the database reporting coordinator, who walked me through a data-driven tool he and his colleagues had created to track the natural gas drilling in Pennsylvania. The map allowed one to drill down (no pun intended) into individual counties and wells to determine both how much fuel is derived from an area and the number of regulatory violations a particular well has seen. From start to finish, it took about three weeks to build out. “I spent time with Scott figuring out what data was available,” Stiles told me, and then worked with Detrow to determine the overall scope of the tool. “We had to focus on what story we were trying to tell.”

Stiles has worked with government data for years, and so knew how to navigate the seemingly insurmountable barriers that can arise when trying to put it to use. “All of the data is available on the well,” he explained. “But it’s in these sort of awkwardly-formatted spreadsheets. There was a process of me looking at that, Scott looking at it, and then going back to the state and saying, ‘This format doesn’t really work for us. I could clean this data up and make it work with a lot of blunt force data cleansing, but why don’t we work together so we can get something that’s easy for us to use but also know it’s going to be accurate?'”

Kinsey Wilson, NPR’s senior vice president and general manager of digital media, said in a phone interview that NPR is launching StateImpact at a time when there’s an erosion of media coverage at the state level. “At the same time that a growing number of significant issues are moving through state governments as things have gotten somewhat more gridlocked at the federal level, we’re seeing a variety of issues — environmental regulation, education, and so forth — [becoming] the subject of state legislation,” he told me. While he sees a particular need for in-depth reporting around some of those issues, NPR didn’t simply want reporters to conduct statehouse legislative coverage: Plenty of local news outlets are still devoting resources to that. Instead, the network saw an opportunity with issues of consequence in selected states.

“We’ve armed them with skills that they’ll be able to use for the rest of their careers, we hope.”

StateImpact also signals a shift in how local NPR member stations operate. For years, they offered some local programming, but mostly acted as distributors for national NPR content. “In the digital era, if they are to continue to thrive and reach the kind of audiences they reach today, they’re by necessity going to have to offer a news package more directly relevant to their audience,” Wilson explained. “The national coverage can be obtained at any number of outlets directly, so the big picture in this effort is to help stations extend their local relevance. They’re uniquely positioned to do so. They’re among the few remaining genuinely locally-owned news institutions in most communities. They have real connections in the community.”

Elise Hu sees other benefits to the StateImpact platform. Hu, the editorial coordinator for the team, oversees the digital editorial vision for all the participating states, and also ensures that the project’s content management system aligns with the organization’s goal to “[give] our readers the Wikipedia-like introduction to the topics that they might be encountering.” Part of her job involves traveling from state to state to meet with reporters directly. In fact, when I spoke to her, she was sitting in an airport, about to head to Indianapolis for a convening of StateImpact’s three education states — Indiana, Florida, and Ohio.

“I think one of the great takeaways of this project, even if StateImpact goes away — which I hope it won’t, but even if it does go away — is that there are 17 member station reporters that might not have otherwise been exposed to this sort of training or this data-driven reporting,” she said. “We’ve armed them with skills that they’ll be able to use for the rest of their careers, we hope.”

Scott Detrow agreed with this notion. “My knowledge of Excel beforehand was pretty minimal, and we had several training sessions on just using that as a reporting tool,” he said. “That is just really helpful in covering an issue where there are all these enormous spreadsheets you have to go through with the reporting.”

Earlier today, Detrow and the team released an interactive web app that focuses on the state’s Marcellus Shale. An app like that, he said, is “not something we would have thought to have done beforehand, and being able to work with people who have the skills to put that together is just great.”

It will be interesting to see how StateImpact develops, especially as it opens up to more states. (It hopes to operate in every state in the country.) But perhaps even more interesting is seeing how NPR will continue to incorporate the lessons learned from this experiment into the rest of its news coverage. With the changing digital media landscape in journalism, fraught with declining revenues and fleeting audiences, no experiment is carried out in a vacuum. And, as Hu pointed out, many of the issues covered in these individual states are of national relevance. “StateImpact is essentially acting as a lab to see how agile we can be, how quickly we can churn out an app,” she said. “And the fact that we were able to go from concept to deployment within a month will be a good story to tell for other members of the digital team at NPR to push that forward as an organization in data app development.”