April 15 was always going to be a big day for The Boston Globe. Marathon Day is traditionally one of the busiest for the newspaper, with its staff deployed around the city following the race, running the race, or on the scene at Fenway for the Red Sox game. It’s a long day, as reporters and editors are up at the break of dawn along with the runners and the rest of the city. So by midafternoon that Monday, after the elite runners had finished, after the Sox beat the Rays in the 9th inning, just about when the “regular” runners were reaching the finish line, the coverage day was about wrapped up.

That, of course, changed quickly. The Boston Marathon bombing was a story that changed the face of the city and grabbed the attention of the world. But, in a smaller way, it also had a real impact on the newspaper’s two-site digital strategy — one that has been seen as both a trendsetter and a recipe for brand confusion.

As one might expect, traffic spiked — and then stayed high. On April 15, 4.3 million unique visitors came to Boston.com, five times the normal traffic, and BostonGlobe.com — the newspaper-like responsive site that normally sits behind a paywall — garnered 1.2 million unique visitors, six times its normal average. That continued throughout the week; as Boston tried to make sense of what happened and the manhunt for the bombers reached its climax five days later, all eyes remained fixed on the Globe’s two sites. Over those five days, Boston.com generated three times its normal pageviews; mobile pageviews to Boston.com doubled; and BostonGlobe.com had 11 times its normal total. On April 19, as Boston was on lockdown as armed cops chased Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev across the region, Boston.com had its highest traffic in the site’s 17-year history.

That kind of rise in traffic would be expected in such a big news event. But the split-site approach added a layer of complication: Instead of setting a coverage plan or dealing with layout and design for one site, the Globe was dealing with two. How readers responded to the Globe is telling of how the paper’s audience perceives the two-site strategy and the different approaches to distributing the news. For BostonGlobe.com in particular, which dropped its paywall for a week, the events of the marathon bombing and subsequent investigation was an introduction to a broader audience both inside and outside of the Boston area.

While the Globe has struggled in the past to create distinct identities for its two websites — some Globe content still appears on Boston.com; Boston.com was “the website of the Globe” for well over a decade, until it wasn’t — the crucible of the marathon bombing illustrated how the paper deploys its resources across the two sites and how they hope to use the two properties to deliver news during breaking events.

One reason the Globe was able to have such a huge response to the bombing is because all the pieces were already in place for marathon Monday. Jason Tuohey, editor of BostonGlobe.com, said the day’s coverage was set and the reporting had begun to winding down. “We had our storylines set, the Red Sox game had come to a close, and then we got reports of the bombings and you sort of go into hyperdrive breaking-news mode,” said Tuohey.

Boston.com had been running a liveblog of the marathon, including information on the elite runners, the wheelchair racers, and other updates from around the course. Teresa Hanafin, director of user engagement for Boston.com, had just returned to the Globe after wrapping up the liveblog from the race media center at the Copley Plaza hotel. “About 15 minutes later, someone came running up to my door and said, ‘Did you hear there were explosions at the finish line?'” she said. “So I walked out into the newsroom and basically stayed there for the next five days.”

What Boston.com and BostonGlobe.com looked like at 1 a.m. the night of the bombings. Courtesy PastPages.

When you strip away all the design, the presentation, and the technology, the mission of Boston.com was very straightforward during the week of the bombing: “It was information that people needed to know in order to go about their lives,” said Hanafin. To make that clear, the site even had for a time a box titled “What you need to know right now” that encompassed new developments in the investigation as well as practical information like business closings and transportation shutdowns.

What readers expect from Boston.com is breaking news and aggregation, and that was no different after the bombings, Hanafin told me. Readers were looking for reliable, meaningful information, whether that was about the latest updates on victims or where the Red Cross was taking blood donations. For most of the week, Hanafin was at a standing desk in the Globe newsroom overseeing Boston.com’s running liveblog, which collected information from Globe reporting, news from other outlets, and tweets from local agencies. Traffic to the liveblog was consistent through the week. Even though the Globe fell victim to some of the same inaccurate information as other outlets, Hanfin said there wasn’t much of a negative response from readers. “I think our users are more forgiving of journalists in those types of breaking news situations than we are of each other,” she said.

With the split of the two sites in 2011, Boston.com was supposed to become the place for local information, entertainment, and reader engagement. That proved true during the week of the bombings, as Boston.com became a kind of community message board for the city, with readers posting how they were feeling, as well as people offering up rooms or couches for displaced marathon runners. “We’ve always been an outlet where people could vent, where they could share or find other like-minded individuals to talk with. That was just magnified,” Hanafin said.

The team at the Globe’s R&D department, Globe Lab, worked with the newsroom to develop new visualizations for reader-submitted content. Chris Marstall, who heads the Globe Lab, said over email his team worked with data visualization staff in the newsroom to created a simple interactive map that asked people to share their story that could be plotted on a map to give a collective experience of the bombing. In another news app, the Globe used its SNAP tool to show 24 hours of Instagram photos from people near the scene of the bombing. Dan McLaughlin, a creative technologist with the lab, worked with Steve Silva to create synchronized annotations of Silva’s now-famous raw footage of the bombing and aftermath.

Boston.com has the benefit of history. Hanafin was on staff for breaking news coverage on stories like the Sept. 11 attacks and the plane crash of John F. Kennedy Jr. From that perspective, BostonGlobe.com is a toddler standing in the shadow of its teenage sister.

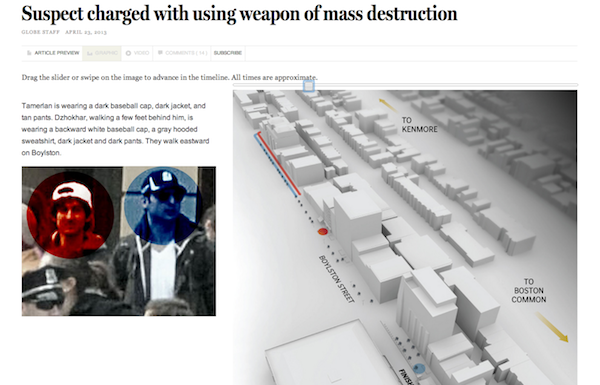

“The challenge, I guess, was the volume of news coming at us, the speed, and I think the fact that there’s no way to take a dry run on something like this,” said Tuohey. “This is unlike anything we’ve ever covered.” In this scenario, the most difficult job wasn’t the reporting, but how Globe staff used the new site to display and deliver information. If the role of Boston.com was to embrace the community, BostonGlobe.com played the investigator and explainer. “What I think Globe.com really excelled at is delving into the issue, the profiles of the brothers, the background, the tick-tocks of what happened, and the interactive graphics,” Tuohey said.

Because of the scope and pace of the story, Tuohey said they wanted to provide context and explainers as part of their ongoing reporting. Often the best method for that was interactive graphics, he said, which can convey details while giving a sense of time and place. “This was a story that obviously had a lot of angles and in the first couple of days one of the biggest questions people had was what happened,” Tuohey said. “When a bomb goes off there’s such chaos around it, and we’re able to report it out in stories, but it also allowed our graphics team to really break out and finely explain what happened.”

BostonGlobe.com enjoys some amount of content flexibility Boston.com doesn’t, partially because of its relative newness — readers haven’t developed a dedicated routine yet — but also because of its responsive-design backbone is designed for elastic layout needs. That meant the site could tinker with its front page to give prominence to large photo slideshows alongside full stories on the latest news in the investigation. Those slideshows, as well as videos, can operate on screen sizes ranging from desktop to tablet to smartphone. Tuohey said that was important because so many people were coming to BostonGlobe.com on mobile during the week.

One of the biggest changes to BostonGlobe.com during the week of the bombings was the addition of a ScribbleLive widget on the homepage. Much like the liveblog on Boston.com, the widget helped fulfill a kind of basic need for timely information, Tuohey said. “At a time of crisis like this, when people really need information, what we saw was that people were turning to us,” said Tuohey. “We had readers in the community turning to both our sites and essentially asking us ‘what’s happening, what’s next?'”

One of the biggest decisions the Globe made was to drop its paywall for BostonGlobe.com for the week. It’s not unusual for news organizations with digital subscription models to open their doors for significant stories; The New York Times and Wall Street Journal both also lifted their paywalls for coverage of the bombings and have done so for events like Hurricane Sandy.

With so many unresolved questions and a very real public safety concern, the Globe wanted to make its information available to the widest possible audience, said Bennie DiNardo, the Globe’s deputy managing editor for multimedia. But DiNardo said he’s not sure whether, in the future, they’ll always throw the gates open for every emergency. That’s because unlike other paywalled news sites, the Globe already has an existing free destination for readers. “The long-term strategy is that Boston.com is the free one and Globe is the paid one. But in an emergency, you’ll get the breaking news off the free site. I don’t know how often we’d do that again,” DiNardo said.

Within a week, BostonGlobe.com was no longer free and all the stories, the first-person narratives from reporters, the chilling tick-tock of the chase for the Tsarnaev brothers, and the comprehensive recount of five days in April, had been pulled behind the paywall. DiNardo said the plan had always been to resurrect the wall when the public safety concern had passed and the story of the bombing and manhunt had reached some kind of conclusion.

The return of the status quo for the Globe has brought a few changes. The breaking-news widget remains on BostonGlobe.com, providing free-to-click links to certain stories. Boston.com now provides more brief summaries from its sister site in the hopes of enticing new subscribers. But there’s a clear push and pull at play between free and paid access. Globe editors admit that dropping the paywall on BostonGlobe.com gave a sizable boost to site’s traffic and introduced its reporting to a new audience. Hard paywalls run into sampling problems; it’s hard for a potential subscriber to know if something is worth paying for if they get to sample it beforehand. But ultimately, if the paper is going to make its reader-backed business model work, it must make the case to more people that reporting is something worth paying for.

One thing editors know they need to address is finding a way to make BostonGlobe.com feel more kinetic by making it clear what stories are new. “Some people still think this is static — more of what was in the paper that day. While we put the term ‘breaking news’ in several places to let people know this is constantly updated, that message doesn’t always get through,” DiNardo said.

The stakes are especially high for the Globe at the moment. The digital subscription plan continues to draw in new subscribers for the Globe, but at a slower clip than its sibling newspaper The New York Times. Meanwhile, the Times is still actively looking for a buyer for the Globe along with the rest of the New England Media Group. All of this is a way to say there’s a lot of uncertainty in the Globe’s future at the moment. For their part, the Globe’s reporters and editors have kept their focus on their work and their city. The two are now more intertwined than ever, DiNardo said. “It’s very gratifying to realize that people trusted us to give them the best information when they needed it,” DiNardo said. “That kind of trust and credibility is helpful in the future. If they trust you, they’ll come back to you.”