Almost from the day The Forward began publishing in 1897 — as a daily, left-leaning Yiddish-language newspaper on the Lower East Side of Manhattan — it’s been losing readers. As Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe learned English and began to assimilate, they’d ditch the paper for competing English-language publications.

“It is just because they read the Yiddish papers that they are interested in the world outside of their own district and become ambitions to know English in order to read the English papers,” Abe Cahan, the Forward’s founder, wrote in 1898. “After they have learned that, they discard Yiddish altogether and read nothing but English.”

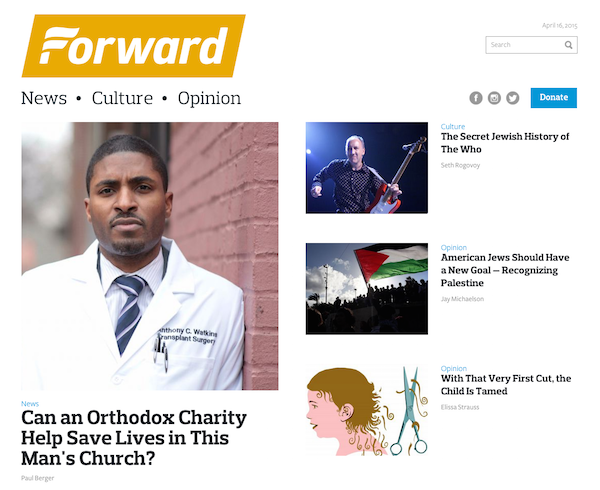

The Forward (Forverts in Yiddish) has long since stopped publishing a daily newspaper, and while it still publishes a biweekly Yiddish edition, its main focus is a weekly English newspaper covering American Jewry and its accompanying web presence.

But even today — decades from its heyday, when it was the largest non-English newspaper in the United States with a circulation of 275,000 in the 1920s — The Forward is still concerned with how to remain relevant to the Jewish community. Its redesign, which launches in print this weekend and online on Monday, caps off a nearly two-year process to reimagine the publication as it tries to remain relevant as it faces prevailing generational changes in both its audience, American Jews, and its medium, print media. (As part of the shift, it’s also changing its name formally from The Jewish Daily Forward to just The Forward.)

T-3 till our web redesign launch! Our founder, Abe Cahan is excited! pic.twitter.com/R43CyjislU

— Jewish Daily Forward (@jdforward) April 17, 2015

Though the challenges facing The Forward certainly similar to those of other newspapers adapting to the online world, the niche audience and limited advertiser base that The Forward and other ethnic papers have can make generating revenue difficult. As a result, The Forward, which is a nonprofit, has become more reliant on philanthropy even as it’s operated at a loss for several years. (In 2013, The Forward Association, the paper’s parent, lost $2.65 million, an improvement from the $4 million it lost in 2012.)

The Forward’s redesign efforts started in 2013 as Forward editor Jane Eisner helped conduct a Pew Research Center study that examined the state of American Jews. The study confirmed that Jews are becoming more secular — 22 percent said they have no religion — and that marriages between Jews and non-Jews are on the rise. But at the same time, 94 percent of respondents said they were very or somewhat proud of being Jewish.

These findings, and others in the survey, led The Forward to begin to rethink how it can approach covering the Jewish community, Eisner told me.

“Our strategy is really trying to create a journalistic enterprise that keeps to its mission,” Eisner said. “We’re fiercely independent. We consider ourselves to be the watchdog of the community — but also to do the kind of journalism that appeals to the kind of people who are thinking, who are exploring their Judaism or their spouses’ Judaism and taking into account a much more pluralistic environment.”

To try and meet those communities’ needs, The Forward last year launched an advice column, called The Seesaw that’s aimed toward interfaith relations that has three different experts write about questions on interfaith relationships. The paper is currently running a yearlong series exploring the Jewish holidays that’s meant to introduce new people to Jewish traditions while also providing new perspectives on them for others.

The Forward has also expanded its coverage beyond New York, where it’s headquartered, starting a series covering Jewish life in every state. Eisner said the paper also wants to emphasize its food coverage, and it’s recently hired a correspondent in Israel to cover everything from politics to culture there.

The Forward faces increased competition from a host of online publications aimed at the small Jewish audience. The newspaper attracts an older slice of that audience, so another goal of the redesign and the new efforts is to try and attract younger audiences. Associate publisher Barry Surman said the paper isn’t expecting large numbers of teens and 20somethings to suddenly become Forward readers, but he said there’s room for growth among older millennials and people starting families.

“We saw that there’s an opportunity for us when millennials are forming families, settling down, deciding how to deal with an interfaith marriage,” Surman said. “Or even if it’s not an interfaith marriage, are the kids going to go to a Jewish preschool or a secular one? Are we going to join a synagogue and get on the track toward a bat mitzvah when the daughter is 13, or is that not something that’s really relevant to our lives and values now? There’s an opportunity for helping those people for — instead of dictating how it has to be, helping people assess and understand the options and how others like them are dealing with the challenges of what it means to be Jewish here today.”

The Forward’s print circulation has remained steady at around 28,000 the past few years, with renewal rates greater than 90 percent. According to Quantcast data, it’s boosted its web traffic to about 704,000 unique visitors in March, up from 439,000 uniques in March 2014.

All American newspapers have struggled with print advertising, but the same changes in American Jewry that are impacting The Forward are also impacting its advertisers, many of whom are Jewish organizations or businesses that want to reach Jewish customers. In a few cases, the paper’s own reporting has helped hasten that. The Forward, in recent years, reported on alleged sex abuse at Yeshiva University, which happened to be a major advertiser. As a result, the university and its affiliates pulled all their advertising, which hurt the paper’s bottom line, Surman said.

To compensate for the reduction in ad revenue, The Forward has put an added emphasis on fundraising in the past four or five years. Last year, it raised close to $1 million through fundraising, Surman said, adding that for too long The Forward has been subsisting on reserves its heyday, when the paper was operated bureaus across the country and even owned a radio station.

“We don’t have vast reserves,” he said. “We cannot operate at a loss for a long period of time as we have for a long period of time.”

But through the redesign, The Forward hopes to continue to reintroduce itself to new readers and advertisers, and also reinforce its importance to current subscribers. The Forward plans on sending out six times as many copies than usual of the first redesigned paper to individuals and groups throughout the Jewish world to introduce them to the paper and to encourage them to subscribe or advertise.

“We have a continuing task to educate our audience that what we do doesn’t come cheap, and we need their help,” he said. “Their subscription is great — but a little more is even better.”