Jess Mador has driven the revamped 1980s-era bread truck all over Knoxville and other towns in eastern Tennessee. The truck has the Knoxville skyline painted on its side along with TRUCKBEAT in bold red letters. Inside, there’s a sound booth.

The truck was the central component of a project launched by Mador along with WUOT, the public radio station in Knoxville, to get out into the community and reach new listeners. They travelled to street festivals, community health fairs, and other local events to interact with people throughout the region.

“There’s something disarming about the truck; it’s a physical, tangible engagement tool…that’s eye-catching and fun, which was part of the idea behind its design,” Mador said recently. “We were able to build buzz and excitement for TruckBeat, and people seemed to want to be part of what we were doing in a different way than with a conventional journalism project where you’re not able to bring your storytelling into the community in quite the same three-dimensional fashion.”

Mador was one of 16 independent producers who in November 2015 embedded themselves with 15 public media outlets across the country to report on underserved communities and to introduce storytelling methods as part of the most recent edition of Localore, a program run by the Association of Independents in Radio that works to connect stations and producers throughout the public media system.This round of Localore, which operated under the theme “Finding America,” featured a wide array of initiatives — from a plan to launch a bureau in Anacostia, a historically black area of Washington, D.C., to a project in Tucson that placed mailboxes to collect stories in Spanish and English “in corners of Tucson where public media doesn’t often visit.”

The Finding America projects wrapped up last November, and on Friday AIR is releasing a survey and a report that share lessons learned from the initiative, offer best practices for other news organizations, and also examine who the Localore projects reached. The survey was conducted by Edison Research; the report was written by lead researcher Mallary Tenore and AIR executive director Sue Schardt and was being published Friday by The American Press Institute.

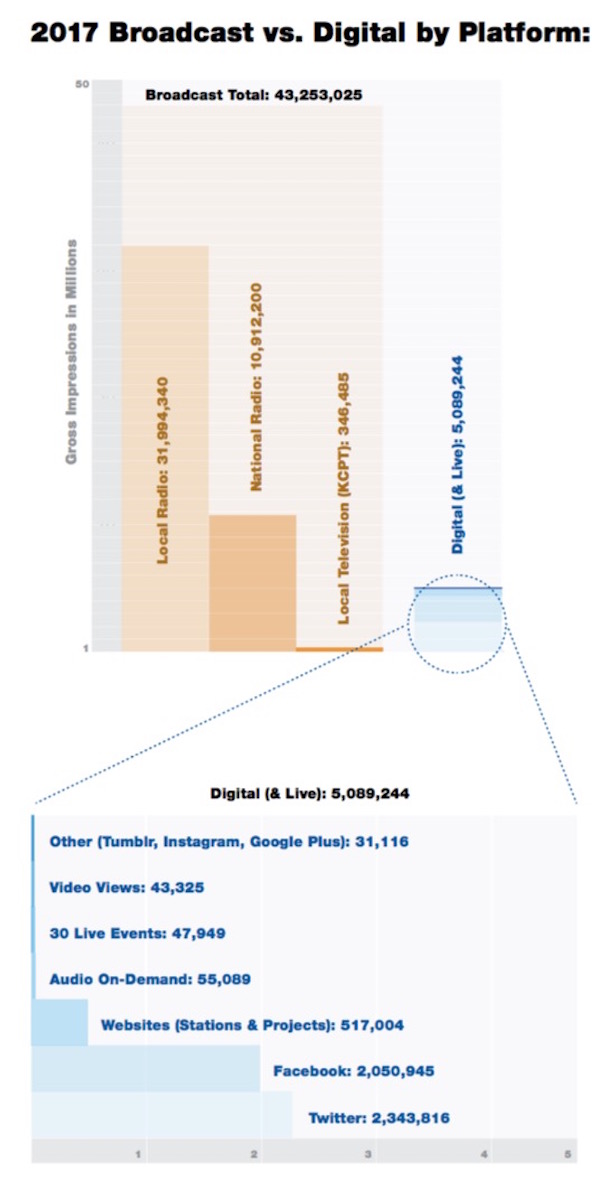

AIR’s Finding America coverage received 48.3 million total impressions, up from 26.8 million in the previous iteration of Localore. A majority of those impressions came over broadcast, but 5 million were digital and 67,369 came from live events throughout the country.

Tenore and Schardt’s report outlines some of the challenges the producers faced:

Some of the obstacles below involve finding ways to challenge traditional journalistic practices and mindsets. Others relate to assumptions about what public media should sound like, and whom it should serve. Still others are institutional — making and sustaining change is hard. These obstacles were identified through our research into the Finding America projects and, specifically, our inquiry into how producers found creative workarounds. The obstacles, and tactics to defeat them, are meant to help you move from breaking news to breaking form — to step away from the conventions of daily reporting and learn to embrace new and innovative forms of storytelling that will engage communities and strengthen the way you approach.

Both documents are worth reading in full, but here are some highlights:

With newsrooms strapped for resources, it can be a challenge for producers to break out of their day-to-day coverage to pursue slower coverage. The report suggests letting the community help drive reporting. TruckBeat at WUOT ran a program called Tenn Words that invited listeners to submit answers to the question “What keeps you up at night?” in 10 words or less. Health was a major concern in the 750 responses collected online and at live events:

“People expressed fears about heart disease, obesity, memory loss, lack of health care services, and the widespread opioid epidemic in Southern Appalachia” — slow-simmer topics that might not ping on a radar tuned to more urgent events. “We identified health disparities as an important, underreported area for TruckBeat to explore.”

The producers also all identified “community collaborators,” influential community members who helped them connect with their larger communities. The report emphasizes that it’s critical for producers to take their time to get to know community members and earn their trust.

In Kansas City, producer Steve Mencher launched a religion initiative called Beyond Belief. As part of his reporting process, he created a steering committee of religious leaders from various faiths: “These were people who I could check in with and also who would challenge me to do better. We adapted where we could, and I used their experience and wisdom to guide the project toward our goals.”

It was sometimes difficult to integrate community collaborators into the reporting process:

There was sometimes confusion around roles and expectations, and uncertainty about how to work with the lead producers’ community collaborators — many of whom didn’t have any previous journalism experience — in a way that wouldn’t be perceived as generating biased coverage. Additionally, some of the lead producers wished they had more support from, and interaction with, their stations.

Finding America’s lead producers ranged from 24 to 62 years old; 44 percent were people of color and 73 percent were women. In comparison, NPR’s staff, according to a 2015 survey, is 77.6 percent white and 54.7 percent female.

They tried also to reach people from different background in the communities they were covering; 39 percent of the community collaborators were non-white, according to Edison. 63 percent of the community collaborators were women, and 54 percent earned less than $75,000 annually.

In 2015, NPR undertook a study to examine the makeup of the sources on its weekday magazine programs, Morning Edition and All Things Considered. They were 73 percent white, down from 80 percent in 2013.

“Public media has developed this segregation of cultures; it seems like an encouragement for all the other cultures to tune out,” said Rachel Hubbard, associate director/general manager at KOSU in Oklahoma. “I feel like it doesn’t start a conversation about sharing culture and creating understanding across boundaries.”

Live events were a pillar of the Finding America program, and a key mechanism for trying to reach communities that don’t typically listen to or watch public media. “Many public media events are geared toward making work that suits a core audience that is predominantly white, older, and affluent,” the report’s authors note. But 36 percent of Finding America’s live event attendees were non-white, Edison found; 35 percent were between the ages of 25 and 34; and 60 percent made less than $75,000.

Finding America events were held in unusual places frequented by people in the community: a drive-in theater in Watertown, New York, a roller skating rink in Baltimore, Maryland, and an elementary school in the heart of New Orleans — where Unprisoned lead producer Eve Abrams held an event in partnership with “Bring Your Own,” a popular roving storytelling project. Perhaps more importantly, Finding America teams brought together people who aren’t usually in the same room — public media’s traditional audience and community members who don’t tune into public media.

One of those events was put on by Every ZIP, a project based out of Philadelphia’s WHYY. Producer Alex Lewis and Jeanette Woods, the station collaborator, held a storytelling block party at The Village of Arts and Humanities, a community arts organization. Woods:

“At WHYY, the only reason a reporter might go to The Village would be to do a piece on conflict or the effects of poverty or crime. WHYY staff and audience went to that neighborhood as neighbors. People were not thinking of that neighborhood through the lens of its stereotype — even for some reporters — as a scary and crime-ridden place. Everyone there was on the same footing, enjoying a very different kind of relationship. And WHYY helped bring that about.

That kind of integrative interaction, a true creation of community, at least within the scope of the event, has always been my goal in public media…People who had never been there — and would never go to that part of the city — got to see it as just another part of the city. People who lived there, who had never heard of WHYY, discovered that the station is a place where their voices were valued, where their experiences could be heard without the filter of ‘reporting.'”