A new report from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism offers a bit more insight into what’s driving distrust in news organizations across the world.

Working with YouGov, the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism polled around 18,000 people across nine countries (U.S., Germany, UK, Ireland, Spain, Denmark, Australia, France, and Greece) to gather qualitative data about people’s trust in news and social media. After respondents were asked whether they agreed with statements like “the news media does a good job in helping me distinguish fact from fiction,” they were invited to share their reasons in an open-ended text box. Reuters’ Nic Newman and Richard Fletcher coded these 7,915 responses to categorize the issues and concerns that are fueling peoples’ distrust.

Here’s some of what they found:

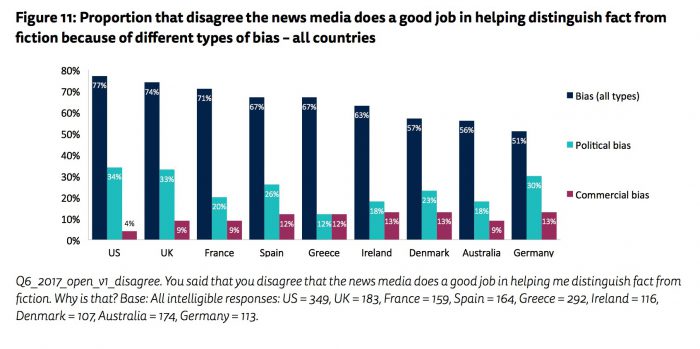

— Why don’t people trust the news? Concern about bias, spin, and hidden agendas. Two-thirds of people (67 percent) cited one of these factors as a reason they don’t trust what they read. Unsurprisingly, concerns about political biases were particularly significant in the U.S., where 34 percent of respondents who distrusted news media cited concerns about political bias as the reason why. This concern is even more acute among those on the political right, who were three times more likely to distrust the news media than those on the left. (Three responses featured in the report: “Liberal media is full of bullshit and lies,” “Fox News keeps it fair; CNN tells us left-wing lies,” and “They are so far to the left, they might fall off.”)

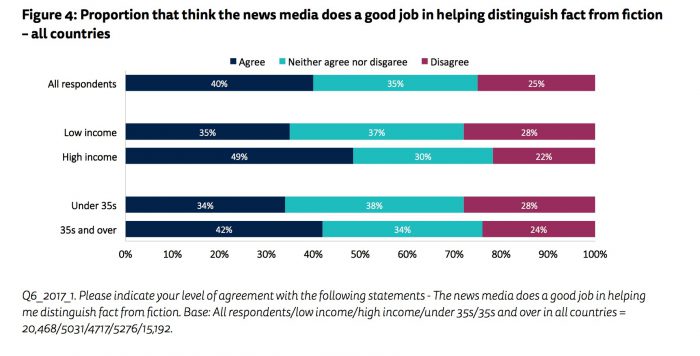

— Trust takes time to build, but can quickly evaporate. One telling finding from the report is that trust in news is significantly higher among people above the age of 35 (42 percent) than those younger than 35 (34 percent) and people of low income (35 percent). The authors suggest that this difference emerges because wealthier, older people are more likely to be invested in the status quo, but also because trust is a product of “stories turning out to be accurate and fair again and again,” which takes time to recognize. Brands, particularly journalistic ones, don’t gain trust overnight, and it may be a long while before news organizations see their renewed emphasis on fact-checking and journalistic transparency pay off among readers broadly.

Of course, it’s a scarily likely possibility that even this could change as new technology makes it easier to fake video footage as well.

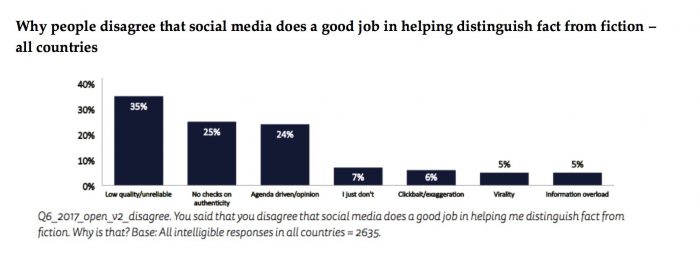

— People have a complicated relationship with social media. It’s telling that, while social media has become a central source of news for many people, just 24 percent of respondents said that social media does a good job of helping them separate fact from fiction. Put another way, just because people are on Twitter and Facebook all day doesn’t mean they trust everything (or even most things) that they read. This is true across age, gender, and income status. Roughly 35 percent of respondents who distrust social media cited the lack of fact-checking and the prevalence of opinion-driven information as the most significant reasons. (Notably, just five percent of these people said they lacked confidence in social media because of a distrust in virality and the platforms’ algorithms, suggesting either that few are concerned about technology’s role in presenting the news they read, or that few are aware of it.)

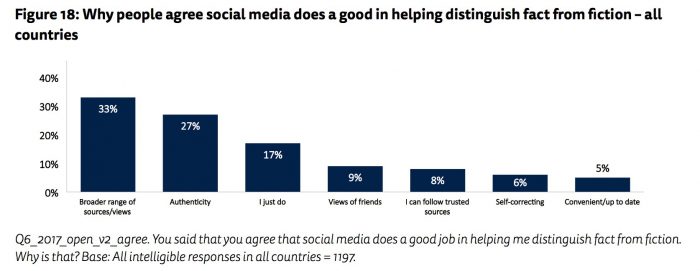

On the other hand, 33 percent of those that do trust what they read on social media point to the inherent benefits of the social platforms, which make it easier to encounter a range of voices that together can often give a fuller picture of a story and reveal gaps in knowledge.

“I can view multiple sources on the same issue or event, and there are people critiquing the articles and posts, so I can see where some things were skewed or reported narrowly,” said one respondent in the U.S.

— Fixing the trust problem will require publishers, platforms, and readers to work together. While news organizations have taken pains to open up their reporting processes and provide readers with a variety of fact-checking services, Newman and Fletcher write that there is still a lot of work to do when it comes to distinguishing “their journalism better from the mass of information available on the internet.” A shift away from digital advertising and toward more reader-supported business models could help news organizations focus less on click generation and more on deeper investigations that will help them build trust with readers. There’s also a lot to be done with creating more representative media organizations that hire a more diverse range of people across age, economic outlook, race, and gender.

Facebook and Twitter, too, must grapple with their role in the trust problem, particularly when it comes to identifying trustworthy news sources on their platforms. (Facebook, for example, recently started to test a feature that would give news organizations a “breaking news” label for their stories.) Indeed, initiatives like The Trust Project and The News Integrity Initiative all involve input from both media and tech companies.The authors conclude:

Rebuilding trust will a long-term process and will require the commitment of publishers, platforms, and consumers over many years. Finding solutions requires a solid understanding of the perceptions and motivations of consumers, and this paper aims to contribute by providing at least a snapshot of current concerns. In many ways, we find audiences ahead of publishers and platforms in demanding change.

The full report is here.