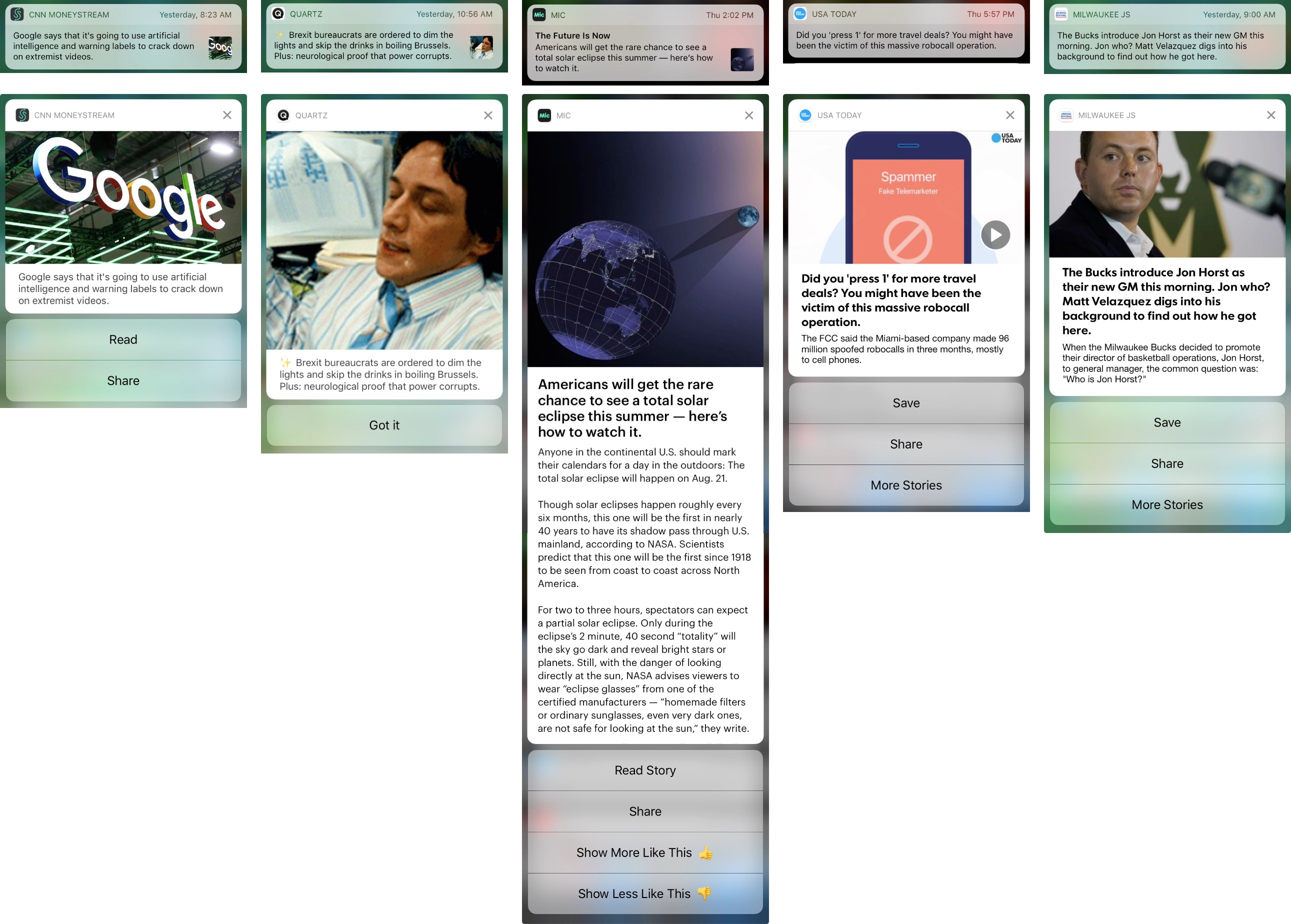

A push alert is large, it contains multitudes.

2017 was a nutty year for push alerts, a Slate feature memorably showed. The timing is good for a new report, “Pushed beyond breaking: U.S. newsrooms use mobile alerts to define their brand,” released this week in collaboration between the Tow Center for Digital Journalism and the Guardian U.S. Mobile Lab. (Knight provided funding, and is also a funder of Nieman Lab.) The report is written by Tow senior research fellow Pete Brown, and I previewed some of his research last month.Brown monitored alerts from 31 iOS apps (this was an iOS-only study), plus 14 Apple News channels, over three weeks between June and July 2017, resulting in a total of 2,758 alerts. He also conducted 23 interviews with audience managers, mobile editors, and product managers from a number of U.S. news outlets.

Since I covered a number of Brown’s top-line findings in last month’s post, I’ll focus here instead on some nitty gritty:

— Most publishers treat Apple News very differently from push alerts (a notable exception being The Washington Post, “whose approach to Apple News was almost identical to that for its iOS app”). In most other cases, though, publishers were less likely to push out breaking stories on Apple News (about a quarter of the Apple News alerts that Brown looked at were breaking news, compared to 57 percent of iOS alerts), and more likely to use “teaser alerts,” emojis, and general-interest stories there.

Why is Apple News different? In part, it’s “the assumption that publishers are dealing with very different audiences in each space,” and that Apple News is seen as “a general interest platform…it seems that Apple News has emerged as a safe space for testing because it is assumed that any missteps made during experimentation will not be seen by (and negatively impact) the outlet’s core audience.”

Paywalls are also a consideration. One mobile editor from a subscription-based outlet:

Probably close to sixty to seventy percent of content goes onto Apple News, but most of it is behind the paywall. We have probably five or six things a day in front of the paywall on Apple News and we only send pushes to things that we free up because the pushes that we send on Apple News go to anybody that follows our channel. So we don’t send the paid push alerts [via Apple News] because we don’t want to train people to consume more news on another channel, where we can’t control the experience, so we basically use it as a prospecting tool and also as sort of a place to expand the visibility of our content. So it’s brand building and it’s also acquisition of new subscribers.

(Also, “more than one interviewee” mentioned technical problems with Apple News. One mobile editor said, “We do sometimes put breaking news alerts [on Apple News], but we noticed a bit of a delay when content publishes to Apple News. So by the time the content actually appears in Apple News, we craft the alert and send it, we’re going to be several minutes behind our competitors and our consumer app, so we don’t often put breaking alerts there.”)

Respondents mentioned benefits of Apple News, too: A surprising amount of traffic on weekends, “a lot of engagement and a lot of signups,” a testing ground that could lead to further experimentation with alerts on the publishers’ iOS apps.

— Publishers are thinking more about “alert language.” There’s a big turn toward more conversational alerts, compared to just headlines. One mobile editor said:

I think the lock screen has become so much more essential for people to find what’s relevant and to find something to read, and I think with that, just based on the notifications that you get from other apps, whether that’s Seamless or Uber, the text is much more conversational and personal. I think news organizations need to go in that direction and extend the voice that they have in their stories so that the same voice and uniqueness is in their notifications.

Another respondent’s publication looked into the data and found that conversational alerts perform better.

When we first started sending out notifications, which was probably three or four years ago, we just had the headline. We sent it in the headline case, and we didn’t care about where it sent you, and our goal above all was to get it out fast…but the more we looked into the data, the more we found that’s not the way people engage with push notifications. It’s really not like a wire headline at all, it’s much more personal than that…People don’t like headlines, they don’t like a push that doesn’t go anywhere, so the result was going away from headlines and making it more sentence case — and we found more success with sentence case — and then we played around with notifications a little more and found that people like it to sound more like a sentence than the headline.

— Metrics are still very squishy, and publishers are guessing as they go along. “By far the most widely shared view across the entirety of our interviews was that metrics as they currently exist provide a very incomplete picture,” Brown writes, “leaving newsrooms to do their best in very trying circumstances.” A lack of metrics doesn’t prevent newsrooms from sending alerts out, but with so few analytics on how well they do, they feel stuck.

Or they find their own ways to hack metrics. Here is one mobile editor “from an outlet that sends alerts on an almost hourly basis”:

We sort of do [use metrics]…We have an in-house tool and we can see, sort of, that when we send an alert we see a spike in traffic. That’s kind of what we see. So we do use that to gauge, ‘That did well, that didn’t do well.’ We kind of look more at what does well and can we emulate that because that’s the easiest thing to do. So we do that: ‘OK, we know that if we send an alert, we see that this one spiked at nine a.m.’ They tend to do better than we might have expected them to do, so we’ll keep sending them. If we see that this alert at X hour isn’t doing that well, maybe we’ll send another alert during that hour to push up audience.

“There is widespread frustration about the difficulty of gauging qualitative aspects of success, such as helpfulness or usefulness — important factors that are not captured via quantitative analytics,” Brown writes. Of course, this is true of a lot of journalism, not just push alerts. The “holy grail” mentioned by one product manager may still be a long way off, but he offered ideas on how metrics for push alerts could improve in the future.

[He] made a particularly compelling case for why metrics need to become more user-centric than the device-based approach that currently prevails. The reason for this, he said, is that many people own multiple devices (e.g., a mobile phone and a tablet device) and will likely have their preferred news outlets’ apps installed and receiving push alerts on all of them. Therefore, an alert that is delivered to two devices may only reach one user. It stands to reason that people are extremely unlikely to open the same alert on multiple devices (not least because, once opened in one place, alerts are often removed from other synced devices). Thus, an alert that reaches a user on three devices (their personal iPhone, work Android device, and tablet, say) and is opened on one will record a thirty-three percent open-rate. However, it is arguably far more valuable to know that the alert achieved a 100 percent open-rate with the user than it is to know that it received thirty-three percent open-rate across that user’s devices. Extrapolating to a full news audience, he said:

‘Once we are able to unite a given user account across multiple devices, we can say not [that] ‘This push was sent to five million devices, let’s see how many of them opened it’; we will be able to say, ‘This push was sent to three million readers, and let’s see how many of them tapped it on any of their devices.’

The full report is here.