If a picture is worth a thousand words, what’s the value of an emoji?

From the skin tones of the human emojis to the existence of the gun emoji, the icons have clearly become intertwined in the our culture of communication. Ninety-two percent of people online use emoji, and more than 6 billion emoji are sent each day. Oxford Dictionaries named one emoji the word of the year in 2015 based on its ubiquity in our interactions. Heck, “The Emoji Movie” was one of the first movies screened in a commercial movie theater in 35 years in Saudi Arabia. But what could emojis actually tell us? How can journalists use emojis in their reporting — and not just as trying-to-be-hip gimmicks?

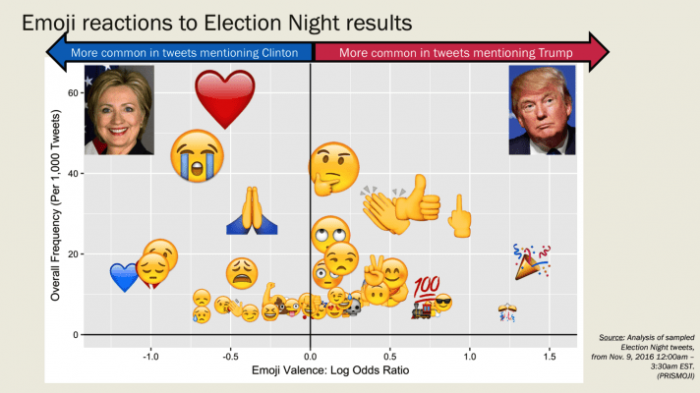

These are the types of question that Hamdan Azhar is trying to dissect. After a watch party for the results of the 2016 election dissolved into tears, prayers, and middle fingers, Azhar — a former Facebook data scientist, Knight Prototype Fund winner (for a separate project), chief scientist at Swiss blockchain startup Zap, and a CUNY visiting professor of data science — found similar sentiments expressed via emoji in his own social media feeds. He poked the Twitter API to see representations of Twitter users’ emotions on all sides of the spectrum and studied the data from 1.8 million Election Day tweets. The top emojis in Tweets mentioning Hillary Clinton — ❤️, 😭 , and 🙏 — represented an outpouring of love and support. The top emojis used in relation to Donald Trump — 🤔, 👍, 👏, and 🖕 — represented both celebration and anger.

“The experience I had in the real world was mirrored in the virtual world,” Azhar said. “Election Day really showed me how people are using emojis to express really raw, powerful emotions on subjects that matter a lot.”

This search wasn’t his first foray. He previously explored the data on emojis in the Taylor Swift/Kanye West drama and the Brexit debate and election, leading to emoji analyses he had published in Vice’s Motherboard as his first works of data journalism. And he’s been finding some intriguing results:

“The hard part is not the technical stuff,” said Azhar, who created the data science lab Prismoji for further study of emoji data science — and its applications in journalism. (His code for analyses like these is now open source.) “The hard part is how to tell a story about this or ask the right questions. This is the most personal form of data science.”

Other industries are culling trends from emoji usage to track fans’ reactions on social media to brands or even the legal implications of using certain emojis. And while journalists certainly have invested heavily in data reporting amid resource restraints, no newsrooms have been regularly parsing what’s been called the fastest-growing type of communication in its two decades of existence.

To be fair, there have been dabbles in the qualitative and quantitative aspects of emoji usage. Quartz published an article using emojis to represent different world leaders’ reactions to the Brexit vote in an attempt of translating pop culture. (Azhar cites this article as his inspiration to take a deeper look at emoji data science which spurred the creation of Prismoji.) FiveThirtyEight has also examined the use of emojis by viewers of the Mayweather-McGregor fight in August. We at Nieman Lab have written about emoji in journalism a bit before as well, such as the prevalence of emojis in mobile push alerts.

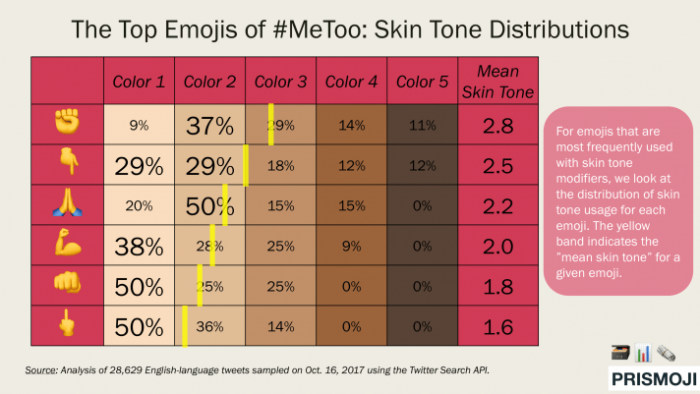

But there’s more to using emojis in data journalism than just cool graphs with more emojis. The Atlantic’s Andrew McGill reported on the relationship between skin tone and emoji by comparing the most-used skin tones on Twitter, noting the low level of white skin tone emojis in Tweets even though “white Twitter users still outnumber their black counterparts four-to-one”:

But this effect may also signal a squeamishness on the part of white people. The folks I talked to before writing this story said it felt awkward to use an affirmatively white emoji; at a time when skin-tone modifiers are used to assert racial identity, proclaiming whiteness felt uncomfortably close to displaying “white pride,” with all the baggage of intolerance that carries. At the same time, they said, it feels like co-opting something that doesn’t exactly belong to white people — weren’t skin-tone modifiers designed so people of color would be represented online?

Former New York Times reporter Jennifer Lee and designer Yiying Lu’s advocacy for the dumpling emoji led to the creation of Emojination for furthering culturally diverse emoji, which has brought not only the dumpling but also the hijab, broccoli, sauna, red envelope, and DNA emojis to the Unicode Consortium. The resources for data on emoji abound: Emojipedia, the resource for documenting emoji, their connotations, and their updates, has been called the Internet’s emoji almanac. Matthew Rothenberg’s Emojitracker site — tallying all uses of each emoji on Twitter in real time — could be considered modern cave drawings with its records from 2013 (which is, you know, a whole ice age ago in emoji years).

💯💯💯 emojitracker: realtime emoji use on twitter https://t.co/L3sWloZmM3

— jack (@jack) January 30, 2016

Azhar’s work with Prismoji could be on the forefront of taking the sheer numbers of emoji usage and working with journalists to create a broader understanding of the emoji in our world.

However, emoji data science isn’t perfect. All the examples mentioned here are based on Twitter’s streaming API, and emojis haven’t been widely tracked or studied on other social media platforms or digital communication methods because of the withheld APIs. There are 330 million monthly active Twitter users globally, in a world where 3.5 billion people access the Internet — and that’s still just half the human population of Planet Earth. Azhar said the prevalence of emojis per topic varies, with trends such as Man Crush Monday featuring emojis in half the Tweets and topics such as former FBI director James Comey’s hearings at the Senate Intelligence Committee having a much smaller proportion of emojis to study. And bots sometimes seem to be as common on Twitter as emoji itself, which could feasibly affect the popularity of certain emojis. Azhar says he only counts a user once per data set to account for bots and retweets, and he’s hoping to explore the Instagram and Kik APIs to parse the emoji data treasure troves on those platforms.

There’s much more emoji data to find on the other side of the 🌈. Azhar plans to reach out to more journalists and newsrooms to encourage data-driven work on culture (such as emojis). Prismoji doesn’t have a solid revenue stream — it’s one of his many side projects — but Azhar said he sometimes partners with media organizations and consults for brands on emoji findings.

“This started as a labor of love and I’ve kept it as such,” Azhar said. “The question I’m asking is very basic — it’s what emojis are people using and what are their emotions around these events. But I can definitely see this informing data journalism in a more powerful way…Something like this allows us to get out of our own bubbles and allows us to get access to a broader swath of human experience.”