There is no single fix for sustainable local journalism. But here’s an attempt at adding another piece of the puzzle: Cleveland.com, part of Advance Local and a digital sister company to the Plain Dealer, wants to see if readers will pay for hyperlocal reporting — via text.

Cleveland.com reporter Emily Bamforth is sending twice-a-weekday texts about road closures, restaurant shifts, city council ordinances, and more in the suburb of Lakewood, Ohio. She’s using Project Text, a tool developed through Advance’s four-year-old in-house incubator and which has been taken up by several Advance sports reporters. Cleveland.com president Chris Quinn is hoping super-specific local happenings will be worth $3.99 per month after a free trial — not including a subscription to the whole outlet, just for the texts — to between 1,500 and 2,000 households. The ultimate goal is, well, seeing if it can sustain the salary of a hyperlocal journalist.

“We’re excited but we know that the odds are stacked against us: Anyone who has tried to tackle hyperlocal has died on the mountain,” Quinn said. But “everybody who’s tried hyperlocal has done it with traditional stories. This isn’t that. This is a completely different approach to connecting people with the community and engaging with them.”Lakewood, where Bamforth has lived for the past four years, is a Cleveland inner-ring suburb of 50,000 people; Quinn described it as “almost every millennial that comes to northeast Ohio at least lives in Lakewood for a while.” Lakewood Together is the 67th project launched on the texting platform and the 11th or so for the Cleveland.com newsroom. Project Text’s guinea pig, setup around the San Francisco elections with reporter Joe Eskenazi, converted 20 to 25 percent of text recipients to paid subscribers.

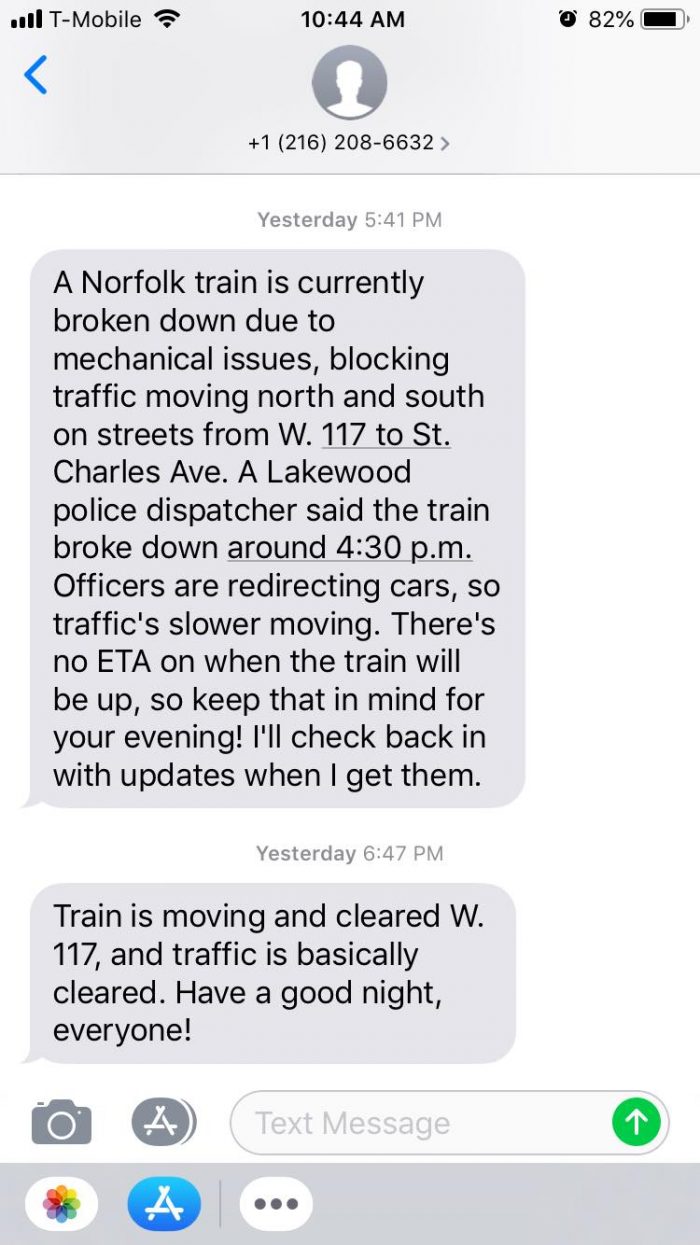

“If I can reach that community [of millennial renters], I can experiment and design the texts I send out a little better so they’re more useful to people — that’s really what it’s all about,” Bamforth said. “It’s making them useful and not just the ideas we have.” She’s not sending out plain articles over text, but more breaking news or insights that people care about:

“Content creators want to monetize the following they’ve worked so hard to build. A lot of users want a more direct connection with the personalities or the journalists they follow,” Mike Donoghue, the founder of incubator Advance Alpha Group, said. “We looked at Twitter and said, ‘there’s a ton of vitriol here and white noise.’ If we could create a platform that was technically differentiated and gave subscribers the unique inside access to the people and info they want, the hypothesis was that people would be willing to pay for this to support the efforts of the hosts in this instance. We’re excited that they have.”

“It’s really journalism as a service, as opposed to this exchange of getting journalism for eyeballs as a service for advertisers,” said senior director David Cohn.

But Quinn is still intrigued by the possibility of ads for bringing local businesses into the conversation, or at help raise their profile. He and Bamforth both mentioned how Lakewood residents care about the vibrancy of small neighborhood stores and how there could be partnerships going forward. “There might even be some room in this for working with local businesses once a week to put together coupons to support them,” Quinn said.

(There is also the very valid point about charging for texts versus access to needed local information, like how Outlier Media sends housing-related reporting for free via SMS, but it’s also sandwiched with the need to pay for local journalism in the first place.)

Cleveland.com gets all the money back from its subscriptions, which hit 600 last month, but Project Text users who aren’t part of Advance can either pay a flat rate as a host or opt for a revenue share based on the total number of subscribers. (Advance hosts do not get a special cut of the money, as some observers have suggested.) Advance Alpha Group, which has also developed The Tylt and others, is a sandbox for the Newhouse-owned chain to sprinkle innovation company-wide. (Chicago Tribune columnist Eric Zorn recently looked at how Advance’s “innovation” of killing off the Ann Arbor News a decade ago has reshaped journalism in his hometown and across Michigan.)Cohn said they could also see Project Text — which will soon be rebranded, stay tuned — being used by politicians, artists, and other Patreon-esque creators. Right now, 85 to 90 percent of hosts are reporters, like a USC student journalist sending out education news, Technical.ly DC’s market editor, 100 Days in Appalachia’s Washington correspondent, and more. Subscriptions range from $2 to $5, but most are around $3.99 or $5 per month, Donoghue said, and they’re seeing churn rates under 5 percent.

Part of the appeal, they think, is that it’s not the mess of social media or even Nextdoor pages. (Bamforth will not send out minor crime news, but it’ll differ from Nextdoor in more ways than that.) Of course, email newsletters can — and have — done this too, but Project Text and Cleveland.com are aiming for a more conversational, casual vibe over text. “This is supposed to feel like a friend texting you while you’re in the coffeeshop line,” Quinn said. When he and Bamforth introduced the idea of Lakewood Together to city officials, they didn’t quite understand that it wasn’t regular articles: “This is not us talking at people. This is the collective ‘we’ talking to each other, and that’s a serious shift in the way people think,” he said.“If you are a personality who would go on ESPN and talk about sports, when the lights come on, you do your traditional reporting into the camera. After the lights go off and you’re having a conversation with everybody else on the set, those are the conversations that are a really good fit for Project Text,” Donoghue said.

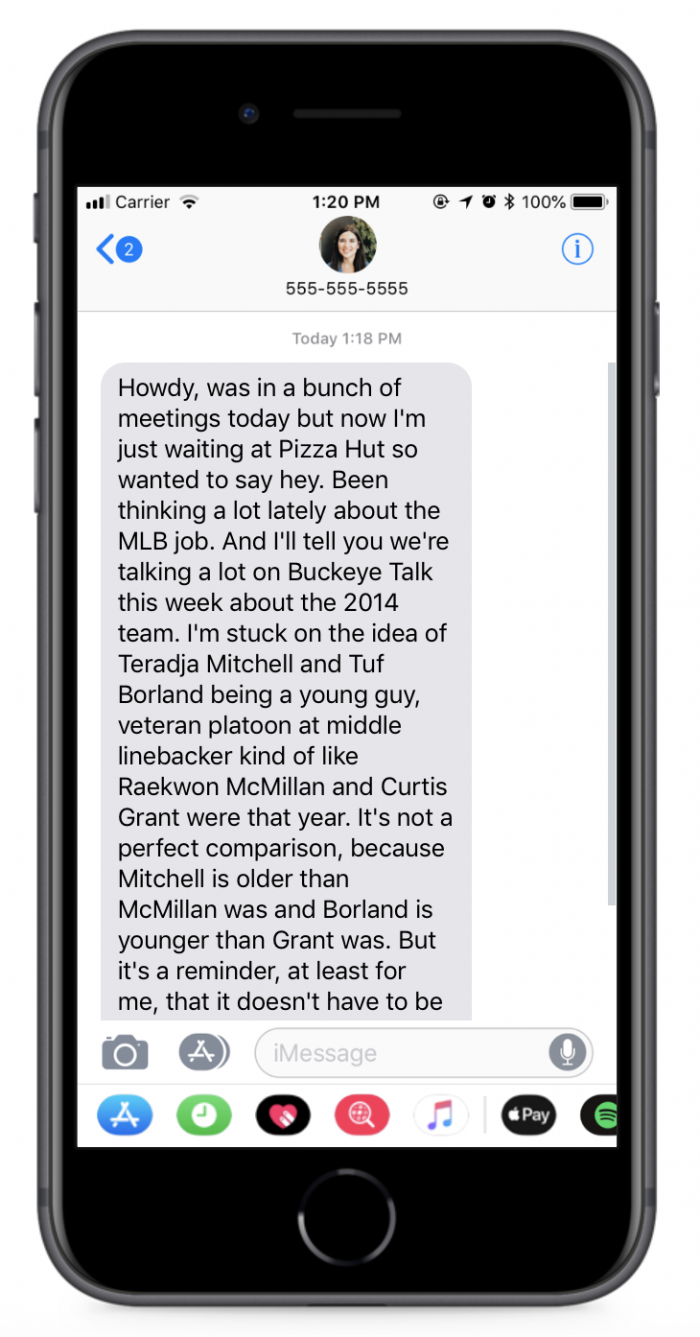

The sports reporters using Project Text have developed quite a following, thanks especially to one promoting it heavily on his podcast, according to Quinn. Here’s an example of Doug Lesmerises’ Buckeye Talk:

Bamforth’s project is still early days, but she said people are already texting her back, something that email newsletters typically miss out on. “One of the things we wanted to be really careful about was being able to facilitate bilateral communication,” Donoghue said. “This isn’t a newsletter in the regard that you receive it, consume it, and move on.”

Lakewood Together’s free trial ends this month, now that Project Text has updated its system to support more discounts and charging flexibility, and Cleveland.com is taking a few months to see if they can build up those 1,500 to 2,000 core subscribers it wants. Project Text is focusing on its most recent hire, JulieAnn McKellogg as director of audience growth, and launching with an unnamed media outlet outside of Advance in the next 30 days.

It’s an ambitious experiment, but that’s also what hyperlocal — or any local — news needs right now.